Archives > Volume 19 (2022) > Issue 3 > Item 08

DOI: 10.55521/10-019-308

Rigaud Joseph, PhD

California State University San Bernardino

rigaud.joseph@csusb.edu

Joseph, R. (2022). A Cross-Sectional Study of the Relationship between Self-Worth and Self-Determination: Implications for Social Work Ethics. International Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 19(3), 108-131. https://doi.org/10.55521/10-019-308

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of IFSW.

Abstract

Racism, discrimination, despotism, and genocide are forms of human rights abuses occurring in various times and places and implying a lack of regard for human dignity. The profession of social work’s dignity and worth of the person core value is consistent with (a) phenomenological theories of self-concept, (b) the Constitution of the United States, and (c) international humanitarian and human rights laws such as the 1949 Geneva Convention and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Previous social work contributions on dignity and worth of clients have not been empirical in nature. In general, ethics and values are not about empiricism, but agreed upon standards of behavior for the greater good. However, scientific support could arguably make a value more appealing, especially in politically fragile times. This study contributes to the literature by determining whether there is a scientific basis for the above-mentioned core value beyond the purview of ethics, theories, and law. Using Well-Being and Basic Needs Survey data, this study compared self-determination outcomes among 7,033 participants based on their perception on their own worth (self-worth). Multivariate regression analyses revealed a strong, positive correlation between self-worth and self-determination. These results are significant for humanistic theories, social work ethics, social work practice and research, as well as human rights.

Keywords: Self-worth, self-determination, social work ethics, humanistic theories, human rights

Background and Purpose

The 2017 Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) identified dignity and worth of the person as one of the six core values of the social work profession (NASW, 2017). First introduced in the 1996 code, this value—alongside service, social justice, human relationship, integrity, and competence—has taken the social work discipline to new ethical heights. Reamer (1998) argued that, at the time of its publication, the 1996 code of ethics was the most significant document in both scope and breadth. Its eclectic nature, drawn primarily from 155 ethical standards and six core values, superseded that of the three previous versions published in 1960, 1967, and 1979 (Reamer, 1998). Subsequent revisions implemented in 2008 and 2017 left the core values in the 1996 code unscathed. The 2017 NASW Code of Ethics expressed the human dignity and worth core value as follows:

Social workers treat each person in a caring and respectful fashion, mindful of individual differences and cultural and ethnic diversity. Social workers promote clients’ socially responsible self-determination. Social workers seek to enhance clients’ capacity and opportunity to change and to address their own needs… (pp. 5, 6)

On what basis have social workers been compelled to respect the dignity and the worth of their clients? Why is the dignity and self-worth of a client important? Is there a scientific basis for the dignity and worth of people in social work? Those are fundamental questions not often raised in the literature on social work values and ethics. Based on the aforementioned statement from the code of ethics, there seems to be an implied connection between human dignity/self-worth and self-determination. The purpose of this study is to determine whether there is a scientific connection between these two concepts.

Literature Review

After social justice, human dignity and worth is perhaps the most cherished core value in social work. Bisman (2004) argued that social work should take pride in promoting its values to overcome 21st century challenges. Internationally, there has been a recent surge in published materials on the aforementioned core value (Anastasov & Kochoska, 2020; Bisman, 2004; Bittencourt & Amaro, 2019; Borowski, 2007; Healy, 2008; Henrickson, 2018; Ioakimidis & Dominelli, 2016; Kamiński, 2008; Szot & Kalinowski, 2019 ; Wessels, 2017). Yet, questions remain in regard to the importance of this core value in social work. There could be possible face value, legal, theoretical, and empirical explanations for the adoption of this value by the social work profession.

Face Value Explanations

At face value, dignity and worth of all people has merit. This core value represents a balm for many souls ravaged by racism, discrimination, despotism, genocide, and other forms of human rights abuses in various times and places across the world. In the west, for example, the United States (U.S.) is still a country with rampant systemic racism. One direct evidence of systemic racism in the U.S. is the fact that this country has known just one non-White president (Barrack Obama) out of 46. This fact implies that the system is tilted in favor of the white racial group and against racial minorities. Another issue that has become the face of systemic racism in the country is police brutality against African Americans. Not only is the number of African Americans killed or beaten by police relatively overwhelming, but usually the manner in which the killing or beating takes place is repulsive and racially radioactive (e.g., the killing of George Floyd and the beating of Rodney King).

Meanwhile, in the eastern part of the globe, multiple news outlets have accused the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) of ethnic cleansing against Uyghur Muslims. National Public Radio (NPR) reported that the CCP used genocidal practices on more than 1.5 million Uyghur minorities in the form of “mass sterilization, forced abortions and mandatory birth control” (NPR, 2020, para 1). All of this occurred on top of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre and the ongoing infringement upon the rights of citizens in Hong Kong. One could understand why many social work scholars recommend a human rights-based approach micro and macro social work practice across the world (Berthold, 2015; Gatenio Gabel, 2016; Gatenio Gabel & Mapp, 2020; Jansson, 2019; Libal & Harding, 2015; Reisch, 2016; Steen, 2006).

Legal Explanations

Social work scholars may point to key documents, including the Constitution of the United States and international legislation, to justify the inclusion of the value in the code of ethics. In fact, this value is consistent with both international humanitarian law and international human rights law, as codified in the 1949 Geneva Convention and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, respectively (Shultziner & Rabinovici, 2012; Sulmasy, 2007).

Theoretical Explanations

Ethics experts may argue that the value coincides with theoretical frameworks that emphasize the importance of human agency (theoretical explanation). In particular, phenomenological approaches such as Carl Rogers’ (1951) personality theory and George Kelly’s (1955) personal construct theory influenced the letter and spirit of the human dignity and worth social work core value. The wording of the above-referenced value dovetails with the key assumptions of Rogers’ (1951) and Kelly’s (1955) phenomenological theories, especially with regard to self-worth and self-determination.

According to Rogers (1951, 1959), everyone has the natural ability to develop and achieve personal goals. However, the perception one makes of himself or herself is crucial in the goal-reaching process. A positive self-perception is likely to enhance self-determination. The opposite is also true, since a negative perception of self can hinder an individual’s progress toward self-actualization. Rogers (1959) also believed that a positive self-perception does not always lead to positive outcomes due to ecological barriers, and that the discrepancy (incongruence) between self-image and life outcomes could be hurtful to individuals in their quest for self-actualization. The recognition of the influence of the environment sets Rogers’ approach toward personality apart from Freud’s. For his part, Kelly (1955, 1963) explained how humans naturally develop personal constructs based on observations. People, in general, collect different types of information from the surrounding environment, synthesize them, and interpret them according to their own experience. This notion of construct is central to how people perceive themselves (Kelly, 1955, 1963).

Moreover, it bears noting that self-worth and self-confidence are related to Bandura’s conceptualization of self-efficacy that suggests considerable overlap in these concepts (Bandura, 1977; 1989). However, the literature contains a kaleidoscopic range of publications that demonstrates—under Bandura’s framework—both similarities and differences between self-concept (self-worth/self-esteem) and self-efficacy (self-confidence/self-determination) (Bandura, 1989; Baumeister & Scher, 1988; Benoit et al., 2018; Bong & Skaalvik, 2003; Bong & Clark, 1999; Byme, 1996; Chen et al., 2004; Cochrane, 2008; Flynn, & Chow, 2017; Hong et al., 2012; Jansen et al., 2015; Marsh et al., 2019; Pajares, 1996; Swann et al., 2007). In line with the literature, this study considered self-worth and self-confidence two related but distinct concepts.

Empirical Explanations

Core values are guiding principles that form the bedrock of social work’s mission (NASW, 2017, p. 2). Because values constitute an integral part of a profession, scholars have voiced support for their adoption in the field of social work (Bisman, 2004; Levy, 1973; Reamer, 1995, p. 11; Timms, 1983; Vigilante, 1974; Younghusband, 1967). It should be noted that social workers promoted values and ethics even before the NASW adopted its first code of ethics in 1960 (Hall, 1952; Johnson, 1955; Pumphrey, 1959). Values, however, are not always grounded in science. Reamer (1995) wrote that values may emerge from strong beliefs and emotions about things that a group of people hold to be true (p. 11). Hence, values are socially constructed.

Scholars have generally considered social work a science (Anastas, 2014; Brekke, 2012; Brekke, 2014; Brekke & Anastas, 2019; DeCarlo, 2018; Guo, 2015; Reid, 2001; Shaw, 2016; Weick, 1991). In the name of science, this study sought to understand the importance of dignity and self-worth of people important beyond the purview of ethics, law, and theories. While the ethical, legal, and theoretical explanations seem enough to justify the adoption of the core value in question, the scientific pursuit in this study could not possibly hurt the science of social work. Quite the contrary. The findings would advance the standing of a profession deemed a science.

Study Rationale

The literature does not provide clarity about the relationship between self-efficacy and self-concept (Pajares & Schunk, 2005). Although related, these two terms are conceptually and empirically different (Gardner & Pierce, 1998; Pajares & Schunk, 2005). Pajares and Schunk (2005) warned that “there is no fixed relationship between one’s beliefs about what one can or cannot do and whether one feels positively or negatively about oneself” (p. 105). However, as previously mentioned, the language used in the ethical code to describe the dignity and worth core value (see block quotes above) contains hints as to why such value is important. There seems to be the unconfirmed hypothesis about a positive relationship between a sense of dignity/worth and a sense of self-efficacy/self-determination.

This hypothesis is consistent with Gardner & Pierce’s (1998) following assumption that individuals who “perceive themselves as highly capable, successful, and worthy with high global self-esteem will generally predict higher probabilities of task success (high self-efficacy) than those who see themselves as less capable, significant, successful, and worthy (low global self-esteem)” (p. 51). This research tested the veracity of this hypothesis. Previous social work contributions on the dignity and worth core value (Anastasov & Kochoska, 2020; Bittencourt & Amaro, 2019; Bisman, 2004; Borowski, 2007; Healy, 2008; Henrickson, 2018; Ioakimidis & Dominelli, 2016; Kamiński, 2008; Szot & Kalinowski, 2019 ; Wessels, 2017) have not been empirical in nature. Hence, this study extends the literature.

Methodology

Design and Data

This study used a cross-sectional design by examining individual and family well-being data collected at one point in time. All data came from the Well-Being and Basic Needs Survey (WBNS) conducted by the Urban Institute in 2017. The WBNS is a publically available dataset with downloadable properties directly from the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) website. The Urban Institute administered the survey online, targeting nonelderly adults as participants (Zuckerman, 2020). With more than 200 variables, this nationally representative survey explores a multitude of topics. These include but are not limited to demographics, workforce participation, family income, participation in safety net programs, material hardship, family financial security, family composition, substance use, disability, sense of self, and sense of agency (Zuckerman, 2020). The last two variables make the WBNS a suitable match for this study by reflecting to a certain degree self-worth and self-determination, respectively.

Sample

The sample consisted of 7,033 working-age adults, those between the age of 18 and 64. Most of the participants were heads of household (75.8%), identified as non-Hispanic Whites (63.2 %), had no children under 18 (61.6%), and lived in metropolitan areas (85.8%). In the same vein, over two-thirds of the sample was made of participants with no college degree. From a gender perspective, a slightly greater number of survey respondents identified as women (56.4%) as opposed to men (43.6%). Regarding sexual orientation, only a minority of respondents (7.8%) reported being from the LGBTQ+ community. Roughly half (50.9%) of the total participants reported a family income above 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL). The remaining half (49.1%) of the sample came from low-income families, those whose annual income falls below 200% of FPL. A similar situation took place for marital status, where half of the respondents (49.1%) were married with the other half (50.9%) not married. Finally, approximately half (47.2%) reported material hardship in the past year.

Study Variables

There were two dependent variables in this study: (a) ability to control the important things in one’s own life, and (b) confidence in one’s ability to handle personal problems. These were two categorical variables recoded as 1 = control/confidence, and 0 = no control/no confidence. The independent variable measured participants’ sense of personal worth. This, too, was a categorical variable recoded as 1 for a positive feeling of self-worth and 2 for a negative feeling of self-worth. A positive feeling means that participants never experienced a sense of worthlessness in the past 30 days as opposed to those who did.

It is worth mentioning that, in most instances, scholars and researchers used self-efficacy and self-worth as predictors of positive outcomes and/or moderators or mediators of relationships between variables (Affuso et al., 2017; Cherian & Jacob, 2013; Choi, 2005; de Fátima Goulão, 2014; Hwang et al., 2016; Merolla, 2017; Motlagh et al., 2011; Samavi et al., 2017; Saragih, 2015; Slovinec D’Angelo et al., 2014; Tannady et al., 2019). In some instances, though, these concepts became outcome variables in correlational studies (Alt, 2015; Barbee et al., 2003; Goreczny et al., 2015; Hong et al., 2012; Korkmaz, 2016; Lent et al., 2009; Mullen et al., 2015; Panadero et al., 2017; Rhew et al., 2018; Van Dinther et al., 2011). In keeping with its hypothesis, this study used self-worth as predictor and self-efficacy/self-confidence as outcome.

The study controlled for 10 different sociodemographic variables: age (under 40 vs. 40 and over), gender (male vs. female), race/ethnicity (white vs. non-white) education (college degree vs. no college degree), family income (low-income vs. moderate/higher income), reported material hardship (1 for yes and 2 for no), marital status (married vs. not-married), metropolitan status (metro area vs. non-metro area), family size (one person family vs. multiple person family), and presence of children in the home (1 = yes and 0 = no). All of these variables were categorical as well.

Data Analysis

The categorical nature of the data required binary logistic regression. The researcher tested the hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between self-worth and (a) participants’ ability to control important things in their lives and (b) participants’ confidence in their ability to handle personal problems. The researcher entered the variables in hierarchical order to better assess the impact of the independent variable, while controlling for the 10 aforementioned predictors. The researcher used the weight variable during the analysis to generate more accurate point estimates.

Results

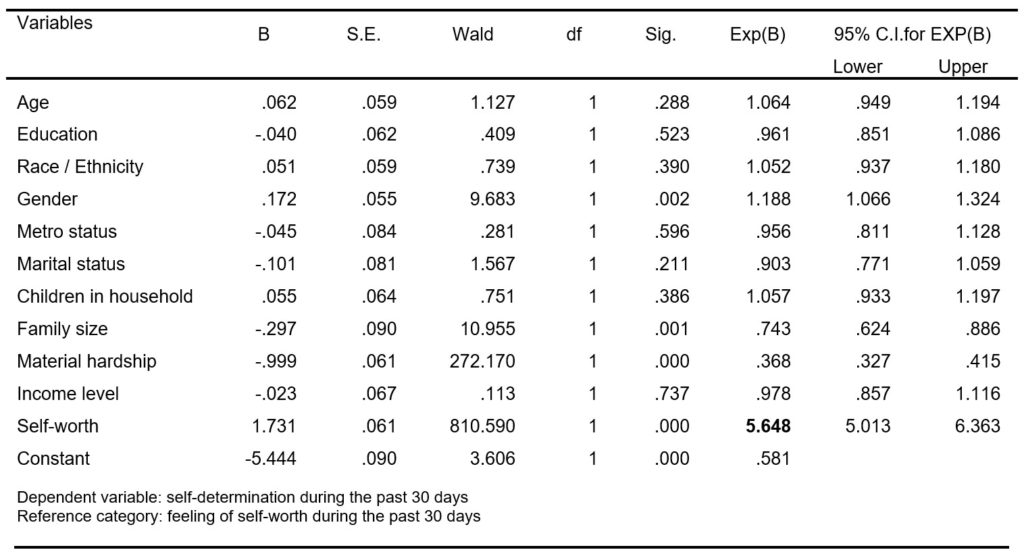

Table 1 displays parameter estimates for participants’ ability to control important things in their lives (self-determination) in regression analysis. These results indicated that, while controlling for all other predictors, the independent variable (self-worth) correlates with the dependent variable (self-determination) to a statistically significant proportion. In fact, participants with a positive view of themselves were almost six times as likely to have the ability to control their own lives, compared to their counterparts with a negative feeling of their worth (OR = 5.65, p < .001). Based on odds ratio (OR) interpretation standards (Buchholz et al., 2016; Osteen & Bright, 2010), the magnitude of the correlation was strong. This finding indicates that there is a positive relationship between self-worth and self-determination, thereby supporting the study hypothesis.

The results in Table 1 also demonstrated statistically significant relationships between control variables and the dependent variable, with a low effect for gender and family size (OR = 1.19, p = .002 and OR = .74, p = .001, respectively) and moderate effect for material hardship (OR = .368, p < .001). There was no connection between the other predictors and the dependent variable. That is, variables such as age, race, metro status, marital status, and income level did not interact with self-determination at the 95 percent confidence level.

In similar fashion, Table 2 exhibits regression estimates for participants’ confidence in their own ability to handle personal problems during the past 30 days (confidence about self-determination). As seen in the table, there was a moderate-to-large association between self-worth and confidence about self-determination. Indeed, participants with a positive self-worth were more likely to report confidence in their ability to handle personal problems than were their counterparts with a negative self-worth (OR = 3.42, p < .001).

Participants who reported material hardship 80 percent (1/.555) were less likely to express confidence in self-determination than their peers who did not face any sort of material hardship. Meanwhile, individuals who live alone, are low-income, non-white, female, and without a bachelor’s degree were less likely to have confidence about self-determination than were their peers who live with other people, have higher income, identify as white and male, and completed a bachelors’ degree or higher. However, the strength of the relationship between family size, income status, race, gender, and education was small. A small correlation also existed between age and the dependent variable, as people who are 40 and over registered higher levels of confidence in self-determination than their younger, under 40 counterparts (OR = 1.3, p < .001). Metro status, presence of children in the household, and marital status did not relate to the dependent variable with statistical significance.

Discussion

Most, if not all, publications on the dignity and worth of the person core social work value have not involved empirical analysis (Anastasov & Kochoska, 2020; Bittencourt & Amaro, 2019; Bisman, 2004; Borowski, 2007; Healy, 2008; Henrickson, 2018; Ioakimidis & Dominelli, 2016; Kamiński, 2008; Szot & Kalinowski, 2019 ; Wessels, 2017). Perhaps this reflects the belief that it is normal for a profession to embrace core values that have no basis in science. In other words, in general, ethics and values are not about empiricism, but about agreed upon standards of behavior for the greater good. However, scientific support could arguably make a value more appealing, especially in politically fragile times. Hence the rationale of this study.

This study strengthens the science of social work’s position vis-à-vis the adoption of dignity and worth of people as a core value, though indirectly (as variables were about the values held by a sample of the population). Through regression analyses, this study found that negative perception of self-worth impedes people’s ability to control their own lives and develop confidence in their ability to solve personal problems. The variables in this study, self-worth and self-determination, take center stage in social work. Hence, through these aforementioned findings, this study expands knowledge on social work research, in general, and contributes to the literature on social work ethics, in particular.

These findings hold implications for micro social work practice in that practitioners are likely to work with clients who exhibit low self-worth. Their encounters usually take place in clinical settings where social work therapists and clients work on common goals. Such therapeutic partnership is consistent with Carl Rogers’ (1951) client-centered approach toward self-actualization. As clients have a natural penchant for self-determination, a client-centered framework would assist them every step of the way. Social work clinicians, therefore, should not lose sight of the detrimental impact poor self-worth can have on self-determination. One way to help during the therapeutic process is to create an environment where clients can develop a positive view of themselves. Another way is the promotion of a human rights-based approach in clinical settings (Berthold, 2015).

These findings also have implications for macro social work practice in that social policies may be construed in a way that erodes self-worth among the most marginalized populations. Social workers are called upon to not only meet the pressing needs of their clients but also to fully embrace a human rights-based approach in practice (Gatenio Gabel, 2016; Libal & Harding, 2015). Social workers can do so through (a) promotion of human rights in clinical practice (Berthold, 2015), (b) inclusion of implementation of strengths-based community practices (Libal & Harding, 2015), (c) adoption of empowerment-driven social policies (Gatenio Gabel, 2016), (d) integration of social justice contents in social work curricula (Gatenio Gabel & Mapp, 2020), and (e) involvement in political activism and social advocacy (Jansson, 2019; Reisch, 2016; Steen, 2006).

By extension, these findings also have implications for human rights. By default, racism conveys a lack of dignity and worth toward others. Despite seeing major increases in minority enrollment, social work is still a white-majority profession. Because white people, in general, do not experience racial prejudice, there is a risk for them to develop a false sense of racial superiority. Hence, white social workers should be careful in how they work with underrepresented populations. Social workers should understand that a sizeable number of their clients comes from minority backgrounds. Some of these clients may experience racial indignities.

Social work has long been a profession that advocates for the rights of marginalized groups. Hence, social workers should refrain from advancing racial stereotypes baked into the fabric of the country. Racial microaggressions can be so subtle that white social workers may not even realize being guilty of them. White people may be subject to racial abuses themselves. Black social workers should be aware of the fact that the political climate can make white clients uncomfortable and resistant to services. Social workers should not internalize ideologies that target specific racial groups in a harmful way. Rather, social workers should become a part of the healing process. Becoming pillars of support for others starts with dignity and respect for others.

Limitations

This study is limited in three significant ways. First, the variables in the model only explained about one-third of the variance in self-determination. This suggests that there are other predictors of self-determination not accounted for in this study. However, the classification table indicates that the logistic regression model applied in this study correctly predicts 72% of the cases, a 17-point increase from its null hypothesis’ 55 % predictive accuracy. In addition, the strong effect size registered for the relationship between the main predictor (self-worth) and the dependent variable (self-determination) shows the model’s goodness of fit.

Second, the methodology in this study does not support inferential interpretation of the results. That is, researchers should not interpret or apply the findings in this study beyond their scope of applicability. Nonetheless, the relatively large sample, the inclusion of control variables in the regression analysis, and the strong effect sizes all point to the significant contribution of this research to the literature. After all, the use of a nationally representative sample to confirm empirically the utility of dignity and worth of the person as a social work value is an original effort in the existing literature.

Third, in its current form, the study is more about the values held by a sample of the population than about social work. Nevertheless, the participants in this study represent potential social work clients, as the profession does not exclude people. In fact, although its focus is primarily on marginalized populations, social work does provide services to clients from all backgrounds. Hence, it is probable that many social work clients would provide responses similar to those expressed by the sample of the population in this study.

Conclusion

This study sought to determine whether there exists a scientific rationale for the inclusion of one core value: dignity and worth of the person. Because social work paints itself as a science, there is a burden to demonstrate that the profession is in keeping with the spirit and letter of science. In fact, critics may question the validity of any major claim or endorsement that falls outside the scientific realm, especially in times of political bickering. A value deeply seated in the NASW Code of Ethics, dignity and worth of the person has not been (or barely been) subjected to scientific scrutiny. This study addresses this gap in the literature by testing the hypothesis that there is a positive correlation between self-worth and self-determination. The findings supported this hypothesis.

The scientific aspect of the findings in this study strengthens the position of the social work profession. As a science, social work can point to the results of this study to promote the dignity and worth of all people, regardless of their backgrounds. Future work should, of course, attempt to address the limitations raised in this study. In addition, future research should focus on establishing the scientific validity of the other social work core values: service, social justice, importance of human relationships, integrity, and competence.

References

Affuso, G., Bacchini, D., & Miranda, M. C. (2017). The contribution of school-related parental monitoring, self-determination, and self-efficacy to academic achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 110(5), 565-574.

Alt, D. (2015). Assessing the contribution of a constructivist learning environment to academic self-efficacy in higher education. Learning Environments Research, 18(1), 47-67.

Anastas, J. W. (2014). The science of social work and its relationship to social work practice. Research on Social Work Practice, 24(5), 571-580.

Anastasov, B., & Kochoska, J. (2020). Respecting the person’s dignity-basis of the code of ethics in social work. International Journal of Education Teacher, 10(20), 56-61.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American psychologist, 44(9), 1175-1184.

Barbee, P. W., Scherer, D., & Combs, D. C. (2003). Prepracticum service‐learning: Examining the relationship with counselor self‐efficacy and anxiety. Counselor Education and Supervision, 43(2), 108-119.

Baumeister, R. F., & Scher, S. J. (1988). Self-defeating behavior patterns among normal individuals: review and analysis of common self-destructive tendencies. Psychological bulletin, 104(1), 3-22.

Benoit, C., Smith, M., Jansson, M., Magnus, S., Flagg, J., & Maurice, R. (2018). Sex work and three dimensions of self-esteem: self-worth, authenticity and self-efficacy. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 20(1), 69-83.

Berthold, S. M. (2015). Human rights-based approaches to clinical social work. Springer International Publishing.

Bisman, C. (2004). Social work values: The moral core of the profession. The British Journal of Social Work, 34(1), 109-123.

Bittencourt, M. B., & Amaro, M. I. (2019). Social work, human rights and conceptions of human dignity: The case of social workers in Lisbon. Portuguese Journal of Social Science, 18(3), 341-358.

Bong, M., & Clark, R. E. (1999). Comparison between self-concept and self-efficacy in academic motivation research. Educational Psychologist, 34(3), 139-153.

Bong, M., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2003). Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educational Psychology Review, 15(1), 1-40.

Borowski, A. (2007). Guest editorial: On human dignity and social work. International Social Work, 50(6): 723–726

Brekke, J. S. (2012). Shaping a science of social work. Research on Social Work Practice, 22(5), 455-464.

Brekke, J. S. (2014). A science of social work, and social work as an integrative scientific discipline: Have we gone too far, or not far enough? Research on Social Work Practice, 24(5), 517-523.

Brekke, J. S., & Anastas, J. W. (Eds.). (2019). Shaping a science of social work: Professional knowledge and identity. Oxford University Press.

Buchholz, S. W., Linton, D. M., Courtney, M. R., & Schoeny, M. E. (2016). Systematic reviews. In J. R. Bloch et al. (Eds.), Practice-based clinical inquiry in nursing: Looking beyond traditional methods for PhD and DNP research (pp. 45–66). Springer Publishing Company.

Byme, B. M. (1 996). Measuring self-concept across the lifespan: Issues and instrumentation. American Psychological Association

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2004). General self‐efficacy and self‐esteem: Toward theoretical and empirical distinction between correlated self‐evaluations. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 25(3), 375-395.

Cherian, J., & Jacob, J. (2013). Impact of self-efficacy on motivation and performance of employees. International Journal of Business and Management, 8(14), 80-88.

Choi, N. (2005). Self‐efficacy and self‐concept as predictors of college students’ academic performance. Psychology in the Schools, 42(2), 197-205.

Cochrane, G. (2008). Role for a sense of self-worth in weight-loss treatments: Helping patients develop self-efficacy. Canadian Family Physician, 54(4), 543-547.

de Fátima Goulão, M. (2014). The relationship between self-efficacy and academic achievement in adults’ learners. Athens Journal of Education, 1(3), 237-246.

DeCarlo, M. (2018). Scientific inquiry in social work. Pressbooks.

Flynn, D. M., & Chow, P. (2017). Self-efficacy, self-worth and stress. Education, 138(1), 83-88.

Fowler, M. (2018). Duties to self: the nurse as a person of dignity and worth. Creative Nursing, 24(3), 152-157.

Gardner, D. G., & Pierce, J. L. (1998). Self-esteem and self-efficacy within the organizational context: An empirical examination. Group & Organization Management, 23(1), 48-70.

Gatenio Gabel, S. G. (2016). A rights-based approach to social policy analysis. Springer International Publishing.

Gatenio Gabel, S., & Mapp, S. (2020). Teaching human rights and social justice in social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(3), 428-441.

Goreczny, A. J., Hamilton, D., Lubinski, L., & Pasquinelli, M. (2015). Exploration of counselor self-efficacy across academic training. The Clinical Supervisor, 34(1), 78-97.

Guo, S. (2015). Shaping social work science: What should quantitative researchers do? Research on Social Work Practice, 25(3), 370-381.

Hall, L. K. (1952). Group workers and professional ethics. The Group, 15(1), 3-8.

Healy, L. M. (2008). Exploring the history of social work as a human rights profession. International social work, 51(6), 735-748.

Henrickson, M. (2018). Promoting the dignity and worth of all people: The privilege of social work. International Social Work, 61(6), 758-766.

Hong, Z. R., Lin, H. S., Wang, H. H., Chen, H. T., & Yu, T. C. (2012). The effects of functional group counseling on inspiring low-achieving students’ self-worth and self-efficacy in Taiwan. International Journal of Psychology, 47(3), 179-191.

Hwang, M. H., Choi, H. C., Lee, A., Culver, J. D., & Hutchison, B. (2016). The relationship between self-efficacy and academic achievement: A 5-year panel analysis. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25(1), 89-98.

Ioakimidis, V., & Dominelli, L. (2016). The challenges of dignity and worth for all: Social work perspectives. International Social Work, 59(4), 435-437.

Jansen, M., Scherer, R., & Schroeders, U. (2015). Students’ self-concept and self-efficacy in the sciences: Differential relations to antecedents and educational outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 13-24.

Jansson, B. S. (2019). Social welfare policy and advocacy: Advancing social justice through 8 policy sectors (2nd edition). SAGE Publications.

Johnson, A. (1955). Educating professional social workers for ethical practice. Social Service Review, 29(2), 125-136.

Kamiński, T. (2008). Social work, democracy and human rights–What follows from the dignity of the human person? Sozial Extra, 32(5-6), 6-9.

Kelly, G. A. (1955). The psychology of personal constructs. Norton.

Kelly, G. A. (1963). A theory of personality: The psychology of personal constructs. Norton.

Korkmaz, Ö. (2016). The Effect of Scratch-Based Game Activities on Students’ Attitudes, Self-Efficacy and Academic Achievement. Online Submission, 8(1), 16-23.

Lent, R. W., Cinamon, R. G., Bryan, N. A., Jezzi, M. M., Martin, H. M., & Lim, R. (2009). Perceived sources of change in trainees’ self-efficacy beliefs. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46(3), 317.

Levy, C. S. (1973). The value base of social work. Journal of Education for Social Work, 9(1), 34-42.

Libal, K. R., & Harding, S. (2015). Human rights-based community practice in the United States. Springer International Publishing.

Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., Parker, P. D., Murayama, K., Guo, J., Dicke, T., & Arens, A. K. (2019). The murky distinction between self-concept and self-efficacy: Beware of lurking jingle-jangle fallacies. Journal of educational psychology, 111(2), 331.

Merolla, D. M. (2017). Self-efficacy and academic achievement: The role of neighborhood cultural context. Sociological Perspectives, 60(2), 378-393.

Motlagh, S. E., Amrai, K., Yazdani, M. J., altaib Abderahim, H., & Souri, H. (2011). The relationship between self-efficacy and academic achievement in high school students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 765-768.

Mullen, P. R., Uwamahoro, O., Blount, A. J., & Lambie, G. W. (2015). Development of counseling students’ self-efficacy during preparation and training. The Professional Counselor, 5(1), 175-184.

National Association of Social Workers. (2017). Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Available at https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

National Public Radio. (2020). China suppression of Uighur minorities meets U.N. definition of genocide, report says. https://www.npr.org/2020/07/04/887239225/china-suppression-of-uighur-minorities-meets-u-n-definition-of-genocide-report-s

Osteen, P., & Bright, C. (2010). Effect sizes and intervention research. https://archive.hshsl.umaryland.edu/bitstream/handle/10713/3582/effect?sequence=1

Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research, 66, 543-578.

Pajares, F., & Schunk, D. (2005). Self-efficacy and self-concept beliefs. New Frontiers for Self-Research, March H. Craven R, McInerney D (eds.). Greenwich, CT: IAP.

Panadero, E., Jonsson, A., & Botella, J. (2017). Effects of self-assessment on self-regulated learning and self-efficacy: Four meta-analyses. Educational Research Review, 22, 74-98.

Pumphrey, M. W. (1959). The teaching of values and ethics in social work education. Council on Social Work Education.

Reamer, F. (1995). Social work values and ethics. Columbia University Press.

Reamer, F. G. (1998). The evolution of social work ethics. Social work, 43(6), 488-500.

Reid, W. J. (2001). The role of science in social work: The perennial debate. Journal of Social Work, 1(3), 273-293.

Reisch, M. (2016). Why macro practice matters. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(3), 258-268.

Rhew, E., Piro, J. S., Goolkasian, P., & Cosentino, P. (2018). The effects of a growth mindset on self-efficacy and motivation. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1492337. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1492337

Rogers, C. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centered framework. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of a science (Vol. 3): Formulations of the person and the social context. McGraw Hill.

Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy. Houghton Mifflin.

Samavi, S. A., Ebrahimi, K., & Javdan, M. (2017). Relationship between academic engagements, self-efficacy and academic motivation with academic achievement among high school students in Bandar Abbas. Biquarterly Journal of Cognitive Strategies in Learning, 4(7), 71-92.

Saragih, S. (2015). The effects of job autonomy on work outcomes: Self efficacy as an intervening variable. International Research Journal of Business Studies, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.21632/irjbs.4.3.203-215

Shaw, I. (2016). Social work science. Columbia University Press.

Shultziner, D., & Rabinovici, I. (2012). Human dignity, self-worth, and humiliation: A comparative legal–psychological approach. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 18(1), 105-143.

Slovinec D’Angelo, M. E., Pelletier, L. G., Reid, R. D., & Huta, V. (2014). The roles of self-efficacy and motivation in the prediction of short-and long-term adherence to exercise among patients with coronary heart disease. Health Psychology, 33(11), 1344-1353.

Steen, J. A. (2006). Guest editorial: The roots of human rights advocacy and a call to action. Social Work, 51(2), 101-105.

Sulmasy D. P. (2007). Human dignity and human worth. In J. Malpas & N. Lickiss (Eds), Perspectives on human dignity: A conversation (pp. 9-18). Springer.

Swann, W. B., Jr., Chang-Schneider, C., & Larsen McClarty, K. (2007). Do people’s self-views matter? Self-concept and self-esteem in everyday life. American Psychologist, 62(2), 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.84

Szot, L., & Kalinowski, M. (2019). Expediting human dignity in social work practices. Roczniki Teologiczne, 66(1), 29-46.

Tannady, H., Erlyana, Y., & Nurprihatin, F. (2019). Effects of work environment and self-efficacy toward motivation of workers in creative sector in province of Jakarta, Indonesia. Calitatea, 20(172), 165-168.

Timms, N. (1983). Social work values: An enquiry. Routledge.

Van Dinther, M., Dochy, F., & Segers, M. (2011). Factors affecting students’ self-efficacy in higher education. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 95-108.

Vigilante, J. (1974). Between values and science: Education for the professional during a moral crisis or is proof truth? Journal of Education for Social Work, 10 (3), 107–115.

Weick, A. (1991). The place of science in social work. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 18(4), 13- 34. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol18/iss4/3

Wessels, G. (2017). Promoting dignity and worth of people: implications for social work practice. Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development, 29(3), 1-16.

Younghusband, E. (1967). Social work and social values. Allen and Unwin.

Zuckerman, S. (2020). Well-Being and Basic Needs Survey, United States, 2017. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.