Archives > Volume 19 (2022) > Issue 2 > Item 08

DOI: 10.55521/10-019-208

Rita de Cássia Cavalcante Lima, Prof., Ph.D

College of Social Work at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

r.lima@ess.ufrj.br

Marta Dias Batista de Leiria e Borges, Ph.D Student

Center for Sociology Research and Studies at ISCTE, IP – University Institute of Lisbon,

Portugal

martaleiriaborges@gmail.com

Juliana Ribeiro Salvador, MSW

College of Social Sciences and Humanities at the Nova University of Lisbon, Portugal

juribsal@gmail.com

Maria Luísa Salazar Seabra de Freitas, MSW Student

College of Social Sciences and Humanities at the Nova University of Lisbon, Portugal

mluisasalazar@icloud.com

Lima, R., Borges, M., Salvador, J. & Freitas, M. (2022). Nothing about Us without Us: Social Worker, Harm Reduction and Anti-Racist Struggle. International Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 19(2), 101-123. https://doi.org/10.55521/10-019-208

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of IFSW.

Abstract

This article discusses the social worker contribution under the guidance of an ethics of harm reduction to ethnic and racial relations in Brazil and Portugal. Social workers in these countries have been committed to ethical values that make us recognize the political direction of the slogan, Nothing about Us without Us, evoked by Black movements and collectives of people who use drugs in a combined anti-racist and anti-prohibitionist struggle. Further, this article highlights the paradox experienced by social workers. On the one hand, in the face of professional ethical values of individual autonomy and non-discrimination to break with the naturalization of racism, particularly when supported by outreach work guided by the model of harm reduction. On the other hand, factors that perpetuate the experience of trauma in people who daily live ethnic and racial inequities.

Keywords: Anti-racist struggle, place of speech, harm reduction, trauma, social work

Introduction

The objective of this article is to discuss the intervention of social work under the guidance of the ethics of harm reduction that focuses on unequal ethnic and racial social relations in Brazil and Portugal. The assumption is that the care provided to people with harmful drug use under the guidance of harm reduction calls on the social work field to recognize the demands led by the subjects themselves who experience combined ethnic and racial oppressions, as well as oppressions derived from the prohibition of illicit drugs, which disqualify the word and threaten the existence of these citizens. In both countries, social work has been called upon to produce knowledge and an intervention committed to democratic values that recognize the anti-racist and anti-prohibitionist struggles of collectives for rights, such as the Black movements and that for users of drugs, respectively.

The Brazilian Social Work Federal Council (CFESS) defined the Code of Professional Ethics with eleven guiding principles such as the “uncompromising defense of human rights and refusal of arbitrariness and authoritarianism” and “commitment to the elimination of all forms of prejudice, encouraging respect for diversity, for the participation of socially discriminated groups, and for the discussion of differences” (CFESS, 1993, p. 24). Likewise, the Portuguese Code of Ethics by the Portuguese Social Work Professionals Association (APSS, 2018 p. 6), defines social workers as the professionals “who aim to define public policies, raise awareness and mobilize people and groups” the defense of their rights, freedoms and guarantees. According to the Portuguese Code of Ethics, human dignity, freedom and social justice are considered the fundamental values of social work. Human dignity is based on the recognition of the identity of people and communities, of belonging to the group, of the validation of experiences, assuming a position that goes beyond impartiality and the principle of non-discrimination. Social work is an openly political profession and academic discipline where social workers should not be neutral in the face of oppression and injustice. That statement is underlined in the code of ethics, refering as a duty the “fight against discrimination and the promotion of equal opportunities and (…) counteracting unfair and oppressive policies and practices” (APSS, 2018, p. 9). In this sense, the principle of non-discrimination goes beyond a negative action or omission, whereby the duty and responsibility of denouncing situations of discrimination and oppression is affirmed.

In turn, in the axis of the value of freedom, the responsibility of the professional class is identified in the creation of conditions for the participation of individuals and groups, also guaranteeing a space of autonomy for the realization of their choices. In the context of social justice, the Portuguese Code of Ethics emphasizes the role of social work in the universal access to fair policies and related goods and services, in turn contradicting unfair and oppressive policies and practices (Ribeiro, 2017, p. 47). Considering the motto “people before politics,” it is up to social workers to advocate for evidence-based politics, guaranteeing the decisions and participation of vulnerable individuals and communities, framed in a bottom-up process. Further, the place of speech, understood as a place socially constructed by oppressed groups that build the condition of political subjects and counter-hegemonic speeches claims that nothing about us without us is addressed without the full participation of those who suffer directly by a violent silencing. The place of speech is an ethical and responsible posture, because “knowing the place from which we speak is fundamental to think about hierarchies, issues of inequality, poverty, racism, and sexism” (Ribeiro, 2017, p. 47). Thus, every discourse is socially located and expresses power relations within a matrix of historical domination.

This article articulates how the places of speech against anti-Black racism in Brazil and Portugal, plus anti-gypsyism in this country, meet the place of speech developed by persons using drugs in their subsequent trajectory of organization and vocalization for rights. This articulation of different places of power, challenges the intervention of social workers as professionals with an ethical values framework that favors the defense of individual autonomy, collective participation, and the fight against prejudice bring professionals closer to the ethical posture required by the orientation of harm reduction. Moreover, with the growth of a conservative morality in society, professionals can also reproduce the historical request for control and punishment over part of the population considered socially as dangerous. Our perception is that it is a paradox, whose control focuses selectively on populations subalternized by a set of attributes, such as the ethno-racial cut, that have the power to activate traumas in people with a long trajectory of suffering, such as persons who use drugs and do not commit to total abstinence are punished with the loss of goods and services provided by social policies. As a paradox, this constitutive and permanent tension in the intervention of social work, challenges professionals to take an ethical posture attentive to the right to diversity and the decline of barriers in access to social policies.

For purposes of this article, social work literature on anti-Black and anti-gypsyism in Brazil and Portugal, the anti-prohibitionist struggle against drugs, harm reduction, and social work intervention were used. From this bibliographical search, information was explored to complement the expertise accumulated by the authors in the field of research, management, care of persons using drugs under a lens of harm reduction and of ethnic and racial diversity. Therefore, the article reposes the choice of the place of speech that social work professionals are developing daily, both with a creative and propositional work linked to the place of speech of the oppressed or with an intervention that reproduces its contribution to the reproduction of control and punishment.

Ethno-Racial Social Relations in Brazil and Portugal

Portugal and Brazil have historical ties relating to what derived from the colonization period between 1500 and 1822. In addition to the Portuguese language and the location of the two countries on the periphery of capitalism, it is worth drawing attention that Portugal was responsible for the largest diaspora of Africans to America. According to Mortari (2015), estimaties include approximately 12 million men, women and children experienced forced emigration to this continente under slavery conditions. Mortari further notes that of this 12 million, primarily monopolized by the Portuguese, approximately 40% were received in the Brazilian colony during the four centuries of slavery. In 1888 was slavery abolished, with Brazil being the last country in the world to abolish slavery. According to Moura (1983, p. 124), “the man-owner was without becoming insofar as he was not interested in any social change.” As a consequence, racial social relations in Brazil were structured with a “White man who did not think about his racial identity or ever as a racialized being, because being White made him a universal being” (Almeida, 2019, p. 264). This emphasizes the need to apprehend the importance of the concept of “place of speech” to know how racism is structured in the social relations today and perpetuated in Brazil and Portugal over the centuries.

The Effects of a Colonized Past

Brazil is one of the most unequal countries in the world. This is a mandatory assumption of any serious analysis of the condition of the majority of its population. By July 2020, Brazil had 211,755,692 inhabitants, with the 2019 National Continuous Household Sample Survey showing that 42.7% of Brazilians declared themselves as White, 56.2% as Black (46.8% as Brown and 9.4% as Black) and 1.1% as Yellow or Indigenous (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2019). The prevalence of Black persons appears in incarceration. However, for every three people arrested, two are Black, according to the Anuário Brasileiro de Segurança Pública 2020 (Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, 2020). The collection of crime statistics showed that from 2005 to 2020, the proportion of Blacks in the Brazilian prison system grew by 14%, while that of Whites decreased by 19% (Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, 2020).

Although both countries assume heavy expressions of socio-racial inequalities, combining open violence with subtle expressions of racism in everyday life, Portugal, as a European country and with a colonizing past, presents dynamics in its power relations and forms of social reproduction of inequality, racism, and xenophobia (Damasceno, 2021). In this sense, it is important to consider that Portugal is a country marked by secular slavery and colonization in Africa and Brazil, and developed xenophobia against the Roma ethnic group, whose group continues to be marginalized in Western societies (Alves & Maeso, 2021). As in other European countries, the Roma community has been the target of ongoing persecution and violent oppression. Currently, there persists an expression of Whiteness which “permanently resorts to the discourse of the historical “self-segregation” of Roma/Gypsy populations” (Alves & Maeso, 2021, p. 159), which holds this community responsible for its own social and spatial segregation and for the perpetuation of its “culture of poverty.”

As we can see, the mantle of Whiteness in the European context is not limited to the phenotype criterion, spilling over to the ethnic and cultural issue. In Portugal, this ethno-racial order is reproduced in the political-institutional sphere, where non-white communities, such as the Roma/Gypsies, are frequently the target of attack by the extreme right-wing movement, currently represented in the Portuguese parliament. This is xenophobia with a political party seat, whose agenda defends the restriction of access to public goods and services for these segments taken as abject subjects – migrants, uneducated and uncivilised (p. 158). For example, the recurrent discourse that assimilates the Roma population to the problematic of “subsidized dependence” on the State, through income transfer programs, (Jornal I, 2021) or even the proposal of implementation of a confinement plan specifically directed to Roma communities in the pandemic context COVID-19, in May 2020 (Casquilho-Martins, Belchior-Rocha & Alves, 2022) – a measure widely applauded in the social networks of the Portuguese extreme right.

Politically and institutionally, there is resistance in addressing the presence of racism. As Henriques (2018) refers, a pact of silence prevails about the violent oppressions and inequalities experienced by communities and individuals because of their color or phenotype. Rare are the moments when either the Portuguese State or other politically and socially relevant institutions assume Portugal as a racialized and racist country. According to the Annual Report on the Situation of Racial and Ethnic Equality and Non-Discrimination 2020, 655 complaints and reports of racism and xenophobia were received by the Commission for Equality and Against Racial Discrimination (CICDR, 2021). “There has been a consolidated increase in the number of complaints since 2014, corresponding to an increase of 50.2% compared to 2019, when 436 complaints were counted” (CICDR, 2021, p. 34). These data reflect a greater awareness of civil society to the violence exerted on racialized people and communities, but it is believed that the numbers do not reflect the reality of lived experience.

Despite the relevance of these data, Henriques (2018) underlines that we cannot delimit the debate of racism to individual attitudes and actions, insofar as it is a complex phenomenon that operates at structural, institutional, and every day at individual levels. These first two forms of expression of racism become difficult to visualize in contemporary Portuguese society. In the words of Kilomba (2020, p. 79), structural racism materializes in the functioning of official structures, privileging “notoriously their white subjects, leaving members of other racialized groups at an obvious disadvantage, outside the dominant structures.” In turn, institutional racism refers to a “pattern of unequal treatment in everyday operations, such as education systems, educational agendas, labor markets, criminal justice and services” (Kilomba, 2020, p. 79).

These resistances and omissions reside in the penumbra of a colonial past that endure in today’s Portuguese society, namely in the myth of Gilberto Freyre’s “lusotropicalism,” which placed the Portuguese at the center of a world created by themselves and praised them as the “good colonizer” who, thanks to their plasticity and adaptation, managed to “sweeten” the colonized (Henriques, 2018). In the work, Casa Grande and Senzala, Freyre (2019) perpetuated the ode to colonialism of the Estado Novo (New State), a period of dictatorship, by legitimizing miscegenation as the result of a non-violent and positive process in comparison to other colonial experiences in other countries. Despite international recommendations and the various efforts of social movements and activists to date, a thorough characterization of racialized and ethnic populations labeled as minority in Portugal has not yet been operationalized (Henriques, 2018). Any analysis of the inequalities experienced by racialized and migrant communities is seen as a mere approximation of the lived social reality.

The constant refusal of the Portuguese State to operationalize a socio-demographic characterization of these communities makes it complicit in the pact of silence on racism. Given the absence of ethno racial data, we can only make mere approximations of the social reality through the nationality of the individuals, which is based on the wrong assumption that racialized people are necessarily foreigners. According to the 2021 Census, 5.4% of the 10,344,802 individuals living in Portugal are foreigners (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2021). In turn, according to the General Directorate of Reinsertion and Prison Services, in 2018, about 29.02% of the inmate population in Portugal would have foreign nationality, with 53.81% of this population coming from an African country (DGRS, 2018). Further, Henriques (2018, p. 31) refers that, “in Portugal, one in every 73 citizens from African Portuguese-Speaking Countries over 16 years old is in the prison system,” which is a proportion ten times higher than the one existing for Portuguese citizens. When we talk about the second most expressive migrant community in Portugal, the Cape Verdeans, this ratio rises to one in 48 people.

The resistances in the assumption of structural and institutional racism in Portuguese society do not go beyond the mere denial of its existence. There is the predominance of a media and institutional “anti-anti-racist” counter-narrative which, by advocating against the “dictatorship of political correctness,” expression of a conservative morality, normalizes, relativizes, and seconds racist and xenophobic violence in Portugal. This morality seeks to preserve the matrix of racial-ethnic domination, where being White is the model of universality and privileges.

As in several European countries, Portugal is also witnessing an increase of ethno-nationalist movements, whereby an increasing number of White and European supremacy is proudly and openly rooted in the predominant and conservative narratives. In Portugal, during the year 2022, the extreme right-wing party CHEGA assumes itself as the third political force represented in the Assembly of the Republic. CHEGA bases its political action on the distinction between the “good Portuguese” and the Other, whose denial of ethno-racial diversity has also grown in Brazil and gained political and institutional representativeness with the beginning of Jair Bolsonaro’s government in 2019. In this way, a hegemonic counter-narrative is perpetuated that places the issue of this Other as a problem of security and the use of state force for the maintenance of public order. Intersecting these oppressions, it is also important to unveil the relationship between racism and the fight against illicit drugs. The international recommendations issued by conferences and documents from the beginning of the 20th century contributed to justify the punitive intervention of the State on those who already suffered from social and racial inequalities. With racism structuring social relations in both countries, the lack of humanity of the Other sanctions the State and society to act with violence.

Even today, Brazil and Portugal are signatories to international conventions that make drugs illegal. The “war on drugs” acts mostly from the legacy of racism, affecting populations living in peripheral territories. In Brazil, updating Benedito’s allusion “from the trafficked to the traffickers” (Benedito, 2016, p.1), the incarceration and murder of the Black population are justified by drug prohibitionist.

Drug Use and Demanding Rights

Brazil and Portugal maintain drug policies on prohibitionist grounds, but they have legislative, ethical, and operational particularities that are also expressed in the process of implementing the harm reduction approach. Although Portugal has been living under a legal framework for drugs that we can classify as deeply humanist since 2001, we know that public policies are one thing, but their implementation and effective exercise is another. The Portuguese response to the social drama that was the experience and survival of the drug-using community in the 1980s and 1990s was exemplary. During that time, there was a consolidation of a network of responses in treatment and legislative support given to harm reduction, a practice that until then had no legal framework. In Law no. 30 on 29 November 2000, Portugal was born as the only country in the world where all forms of harm reduction, even the most experimental ones, were foreseen as significantly reducing the incarceration of people for engagin in illicit drug use. However, it is important to note that the lack of a legal framework did not prevent several countries, including Brazil, from moving towards the practice, thus protecting their communities, and making the pragmatic vision of effective human rights that is harm reduction prevail.

In this direction, Soulet (2007) calls attention to the fact that persons who use drugs should not be considered as delinquents or patients, but as citizens, bearers of rights and obligations. The idea is to go through and contribute to the construction of a path in which we adopt an appropriate language from the scientific point of view and health promotion, which transmits the same dignity and respect offered to people with other health conditions. Thus, this emergence of harm reduction in Portugal and Brazil inaugurated a new moment of listening and participation of person engaged in illicit drug use since those who used drugs would only have their speech recognized if it was to ask for help for abstinence or to testify how they had overcome the addiction. In both Brazil and Portugal, there was a lack of listening to this population in their condition as persons who consumed drugs in a harmful way, who demanded care and involvement in the construction and effectiveness of public policies. As a daily practice of harm reduction, these countries had not yet appropriated the importance of integrating people as peers or experts of experience, where being a user of licit or illicit drugs was to be an actor of his own path, adding the perspective of the user to the intervention of the professional.

Still existing in both countries, and reinforced in Brazil, is the conception that persons who use drugs do not participate and do not (re)know this space or place of speech. However, the leap of these last 20 years was substantial, but still restricted to large urban centers. The work in progress, which is only possible through the lens of harm reduction, requires the permanent deconstruction and reflection proposed by Boaventura Sousa Santos, “We have the right to be equal when our difference makes us inferior, and we have the right to be different when our equality disqualifies us. Hence the need for an equality that recognizes differences and a difference that does not produce, feed, or reproduce inequalities” (Santos, 2003, p. 56). In turn, it is important to ensure that the intervention happens “with” the peers, as producers of intervention and co-producers of services (Martins 2020, p. 50) documenting this whole process so that it is possible to evaluate and evolve towards the effectiveness of civic and political participation of communities directly linked to drug use.

When we have social work in spaces with the presence of peers, we consider that because it is a profession trained to understand the fundamentals of social relations, to better intervene on the social needs of the people assisted, there is a favorable plasticity to capitalize on the work with peers or experienced experts. While this work has multiple advantages for both actors, the social worker must be aware of the other, at the same time both a user of drugs and part of the team. The intervention of peers, due to the increased vulnerability of recognizing themselves in the people assisted and, in their pathways, can trigger traumas. The triggering of traumas, due to fragmentation, can have a negative impact on them and the stability of the whole team. The bet on a diverse team requires the activation of multiple support mechanisms to reduce the damage, both in those individuals and in the professionals. In turn, this may increase effective advocacy for rights, independently of the different competencies in the collective work. It is important that social work can be one of the teams ensuring that nothing about us without us has space to exist and resist, otherwise the value of participation becomes merely consultative and not deliberative.

Harm Reduction, Anti-Racist Struggle, and Social Work Practice

It is impossible to dissociate the mechanism of the war on drugs from the various oppressions that justify it and result from it, such as anti-Black racism and anti-LGBTQIA+ movements. Prohibitionism and the control exercised over bodies and racialized people who use drugs become modes of punishment and perpetuation of violence, objectifying such individuals as targets to be marginalized. Considering the principles of harm reduction with drug using communities, and as Daniels et al. (2021) emphasize, this global war on drugs based on racism and colonialism, should be replaced by strategies based on science, health, and social equity. Thus, it is impossible to take harm reduction without a critical look at the racialization of substance abuse, of the judicial and incarceration systems, of the disparities in access to housing, documentation, health and social services. It is a web of complex intersections and, in some ways, with limited focus in political agendas and academic research.

As a predominantly female profession, social workers in Brazil and Portugal were associated with a conservative, Catholic and control-based professionalization of the social order, perpetuating hegemonic narratives, whose attributions were exclusively directed towards meeting the State’s responses to the “social issue” (Iamamoto & Carvalho, 1988; Martins, 1995). As black workers earned their income through mostly informal work activities, they also remained without equal access to public social policies. The distance of the profession from recognizing the racialized content contained in social demands, gives us the idea of considering that harm reduction can be the missing link to understand all the racialized content within the community of people that use drugs. Harm reduction approach can contribute to a more qualified intervention within the paradox between reproducing control over these “subaltern” masses and participating in their emancipatory struggles for rights that complement theories.

Public policies, when in relation to issues of social hierarchy and socioeconomic position, circumscribe to survival, and people who use drugs are always conditioned by all dimensions of the social determinants of health, taking the drug is only the role of another stone in the social gear. Oftentimes, the continued use of psychoactive substances can have a significant impact on the individual’s life and the driver of this problematic use comes from a place of trauma, associated with multiple dimensions. The impact they have will also condition how the person will manage the suspension of consumption. Knowing that the access to some health services, social assistance, or other social policies is dependent on the suspension of consumption is the reinforcement of the initial trauma (Maté, 2018). Those who know they can demand health services, even while maintaining consumption, are in a place of privilege, because this very place only becomes a place of speech if the user recognizes himself as a citizen. Thus, the social determinants of health can also serve as a social silencer (Goelitz,2020). Tatarsky (1998) describes the impasse of people in their relationship with substances as those who:

(…) seek help for issues other than substance use, are routinely deprived of psychotherapy and referred to substance abuse treatment, while substance users who do not desire or accept abstinence do not receive treatment. Abstinence is the criterion of success, for the client and for the person providing a service in treatment, and a prerequisite for any other issue that needs to be addressed (p. 1)

Accessibility is conditional on abstinence, yet there is nothing accessible about this process. It should be reinforced as a mantra that people do not want this place of suffering. If it were not for the suffering of themselves, their families, and communities, they might choose to continue using drugs. At the beginning is the pleasure and the relief of displeasure and this issue cannot be minimized, because it is central to understanding and connecting with the person. Only in a relation with the other is it possible for social work to provide an effective and emotional support to the person.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “Research shows that the social determinants can be more important than health care or lifestyle choices in influencing health” (WHO, n.d.). On one hand, this information highlights the importance of social policies with their community intervention structures, which regularly bet on intervention with people; and in drugs the harm reduction structures, which allow to create the bridge with impact projects that address the issue of housing. On the other hand, it reminds us of the importance of social work, and the need for investment by social workers not only in practical terms work with the populations, but also in political work terms. It urges to document the social changes and challenges of social work, their processes in order to influence and create lobby for more and better public policies, namely in the area of drugs, but transversely to various publics where the social determinants of health. Social workers need to have a strategic political emphasis when people, like people that use drugs see the are more precarious, weakening and compromising the chance of participation of users, especially when they compose racialized masses of the peripheries of the cities, compromised.

When we relate the social determinants of health with trauma, we can identify how all of them can be activators of trauma that people tend to oppress as a survival strategy. In addition to social determinants as contributors to trauma, stigmas assigned to persons who use drugs (e.g., junkie) often hold them back in the rise of the social lift and the mortgaging of quality of life in its most diverse dimensions. The gateway to trauma is precisely in the intersection between these two concepts, as Goelitz (2020) notes:

Since life stress following a traumatic event is a risk factor, people who are marginalized in any way have a greater vulnerability to harm. This includes those living in poverty, with less education and opportunity for work or those dealing with cultural issues such as prejudice, immigration, or the inability to speak the primary language of the community. Not only do these individuals have a greater risk, but they also tend to have more difficulty obtaining assistance from professionals (2020, p. 109)

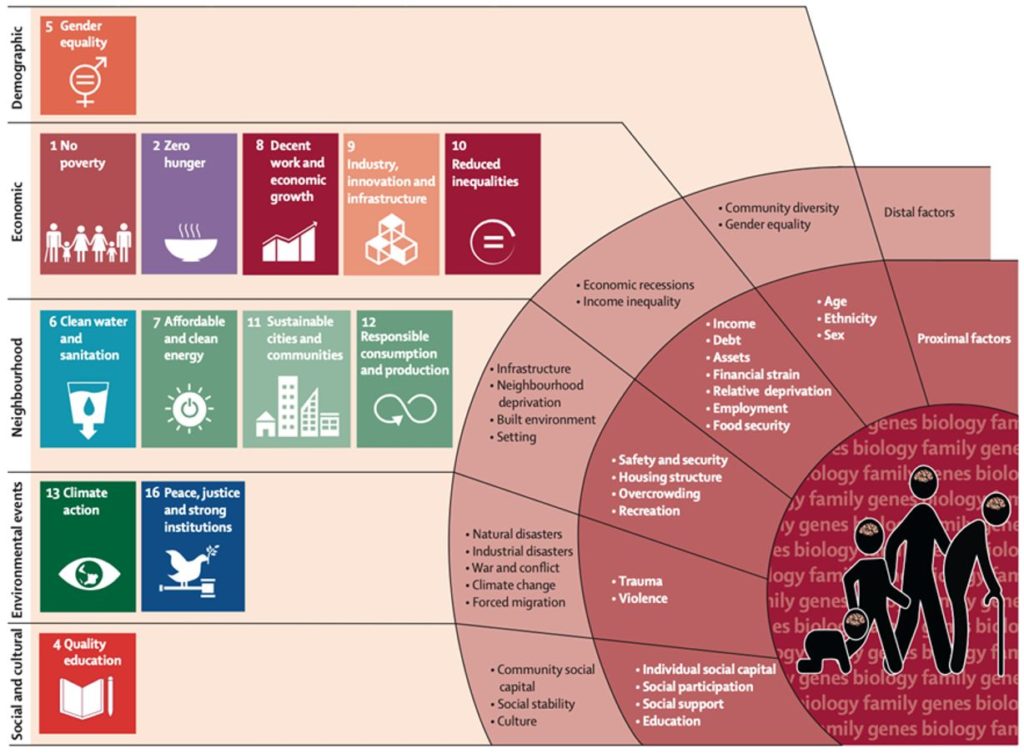

The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development (2018) published a figure (Patel et al. 2018) that marks the relation between Mental Health, Social Determinants of Health and the Sustainable Development Goals. This relation allows us to identify the main concepts of this article and their correlation as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 allows us to observe the dimensions that have been discussed throughout this article – Social Determinants of Health as the trigger for the disease, where all dimensions of social service work are included, whether individual, family, or community (Heyman, 2018). These dimensions are: social and cultural, environmental events, neighborhood, economic and demographic. At the demographic level, we can find the issues that impact health, which are also the issues of importance to diversity, but also the fragility of diversity when crossed with discrimination, and discrimination based on ethnicity. If we consider different layers of discrimination, to this we can add drug use, which becomes the perfect storm to activate attacks on human rights. To this is added the environmental dimension, where trauma arises as a consequence of environmental factors that we do not control. Social work is called upon to intervene in the meso or proximity dimension, and influence the distal dimension for one part and the individual for another.

Culture and ethnicity increases the risk of trauma (Goelitz, 2020, p. 120), and that’s where social workers need to be, but with the necessary skills to respond to trauma and people with a repertoire of traumatic life events. The notion of trauma will allow us to understand the pain and behaviors of others, especially with persons in vulnerability. Social workers must internalize that the ethics of care is also about a healing process, which Goelitz defines as “the healing process includes attaining physical, emotional, social, and financial stability” (Goelitz, 2020, p.132), and this is why we need to be active promoters of supporting safe spaces for persons experiencing vulnerabilities while also investing in the intervention of diverse peers with diversity implying a diversity of life history, ethnicity, and gender, for example.

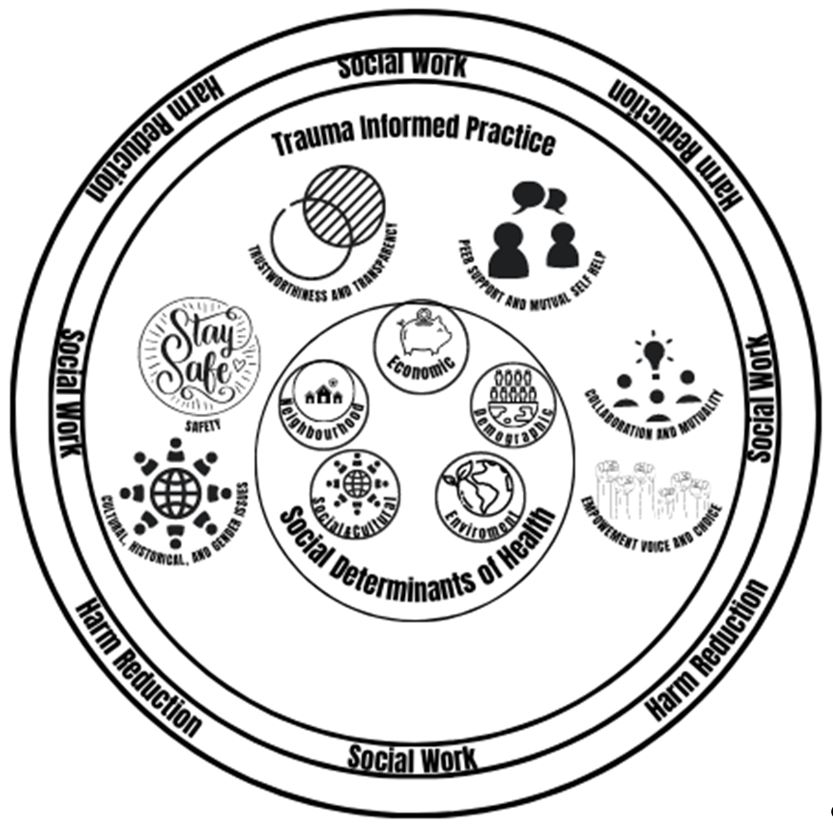

There is an irreversible potential of trauma in the barriers to address the social determinants of health, which are transversal in a general way in the globalized world. However, when this is added to public policies of persecution and social control, the oppression worsens, turning what could be a place of speech into a place of social gagging. An example of this are the situations of social emergency that many people who use drugs experience, which transition from emergency to permanence due to stigma and lack of answers. This social drama increases trauma, either through prolonged use of unsafe spaces such as nightlife, public bathhouses, or social cafeterias. Long periods of vulnerability perpetuate and deepen the trauma, becoming an alley from which few leave without deep scars, deeper than those that led to the beginning. In this sense, the system itself perpetuates trauma, and social and health services are no exception. As a result, Figure 2 represents our intervention framework proposal for social work intervention that suggests an holistic approach to address social determinants of health, with trauma informed care and harm reduction intervention.

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) document titled, Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach (2014), Trauma Informed Care Principles are: Safety, Trustworthiness and Transparency, Peer Support, Collaboration and Mutuality, Empowerment and Choice, Cultural, Historical and Gender Issues. We advocate that social work intervention in the social determinants of health should ensure the inclusion of trauma informed care methodology integrated into a harm reduction model. The harm reduction model implies the deconstruction of a framework of beliefs and values in order to allow the relationship with the other person where they are, assuming the time of the person and not the time of the institution or social worker.

Unlike Brazil, Portugal made a difference in legislative terms in the humanization of the law towards the person who uses drugs, becoming a world example (Drug Policy Alliance, 2018), yet it still has significant steps to take in the reconceptualization of the support spaces for people who use drugs. Further, it is essential to ensure that financial support to community spaces in the area of drugs is maintained, especially in the post pandemic Covid-19 period (Borges, 2020). In addition, it is critical to ensure an awareness that the intervention and the interveners of these spaces may themselves be promoters of trauma and (re)traumatization. It is necessary to teach and learn to understand the complexity of caring as a demand of humanity.

Conclusion

The importance of bringing the focus of harm reduction, peer support, social work and their potential to address unequal ethnic and racial relations is because harm reduction can be connected to community intervention, thus being the first effectively constructed bottom-up effort that reaches the needs of people who use drugs. In addition, due to its pragmatic identity matrix and intervention in human rights, it tends to be a promoter of non-judgmental spaces, attracting professionals willing to ensure an intervention without prejudices. Peers act as an essential element to guarantee a leveled intervention, promoters of effective speech spaces guaranteeing an effective participation of people who use drugs in the social and political space. This participation requires the need for professionalization of peers as a guarantee of less precarious working relationships and more recognition of their expertise, as already happens with other mediators contexts such as Roma mediators in schools or experts with experience in community intervention. Therefore, the ethical values of Portuguese and Brazilian social work are in line with the harm reduction orientation through the defence of self-determination, non-discrimination, and human rights.

This ethical knowledge allows us to uncover the social determinants of health, such as ethnic and racial inequalities, which affect people in countries where this violence is perpetuated daily. However, given the naturalisation of ethno-racial inequalities in these countries, social workers may also reproduce racial discrimination in their interventions, even when attentive to the ethical orientation of the profession, because it is neither automatic nor spontaneous to recognise the racism that is maintained within our worldview and practice. The same challenge is raised and amplified when the intervention addresses people who are drug users from disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups. As social workers intervening in the field of drugs, we consider and recognize the aggregative potential of the need for public policies with strategies directed to the social determinants of health, in the creation of trauma-sensitive teams and communities and in the promotion of non-judgmental spaces. The space is the relationship that can happen, as Trevithick (2012, p. 307) said, “Interventions mark a meeting point – a place where two paths meet – and where our task is to work from our best selves to begin to understand the situation being presented and what our next step might be.” As a result, Figure 2 represents our model proposal for social work intervention that includes trauma informed care and harm reduction considerations.

References

Almeida, S. (2019). Racismo estrutural. USP. São Paulo: Pólen.

Alves, A. R., & Maeso, S. R. (2021). Raça/espaço pela mão da política local: anticiganismo, habitação e segregação territorial. In S. R. Maeso (Ed.), O Estado do Racismo em Portugal. Racismo antinegro e anticiganismo no direito e nas políticas públicas (pp. 157-180). Tinta da China.

APSS (2018). Código Deontológico dos Assistentes Sociais em Portugal. https://www.apss.pt/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/CD_AS_APSS_Final_APSS_AssembGeral25-10-2018_aprovado_RevFinal.doc-1-converted-1-Cópia.pdf

Benedito, D. (2016, November 5). De traficados a traficantes, a população negra é a maior vítima da guerra às drogas. Geledés. https://www.geledes.org.br/de-traficados-traficantes-populacao-negra-e-maior-vitima-da-guerra-as-drogas-entrevista-com-deise-benedito/

Borges, M. (2020). O impacto da crise da COVID-19 na intervenção de Redução de Danos. Análise crítica sobre intervenções e atores sociais | entre a crise e a oportunidade. Cadernos da Pandemia vol 4, (Re)Inventar a intervenção social em contexto de pandemia (pp. 15-23). Ed. Instituto de Sociologia da Universidade do Porto https://ler.letras.up.pt/site/default.aspx?qry=id032id1730id2882&sum=sim

Brazilian Social Work Federal Council (1993, March). Institui o Código de Ética Profissional dos(as) Assistente Social e dá outras providências. Resolução CFESS nº 273/1993. https://www.legisweb.com.br/legislacao/?id=95580

Casquilho-Martins, I., Belchior-Rocha, H., & Alves, D. R. (2022). Racial and ethnic discrimination in Portugal in times of pandemic crisis. Social Sciences 11(5), 184. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/socsci11050184

CICDR. (2021). Relatório Anual 2020—Igualdade e não Discriminação em Razão da Origem Racial e étnica, cor, Nacionalidade, Ascendência e Território de Origem. https://www.cicdr.pt/documents/57891/0/Relat%C3%B3rio+Annual+2020+-+CICDR.pdf/522f2ed5-9ca6-468e-b05d-f71e8711eb12

Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development. Lancet, 392(10157), 1553-1598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-XRibeiro, D. (2017). O que é lugar de fala?. Letramento. https://www.sindjorce.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/RIBEIRO-D.-O-que-e-lugar-de-fala.pdf

Damasceno, H. de J. (2021). Experiências de jovens afrodescendentes/negras na educação profissional: Contribuições ao serviço social em Portugal e Brasil [Doctoral thesis, Iscte – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa]. Repository Iscte. http://hdl.handle.net/10071/21342

Daniels, C., Aluso, A., Burke-Shyne, N., Koram, K., Rajagopalan, S., Robinson, I., Shelly, S., Shirley-Beavan, S., & Tandon, T. (2021). Decolonizing drug policy. Harm Reduct Journal, 18(120). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00564-7

Direção Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais (DGRSP), Estatísticas Prisionais Anuais, Lisboa: Ministério da Justiça, 2018. http://dgrsp.justica.gov.pt/

Drug Policy Alliance. (2018). Drug decriminalization in Portugal: Learning from a health and human-centered approach. https://drugpolicy.org/sites/default/files/dpa-drug-decriminalization-portugal-health-human-centered-approach_0.pdf

Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública (2020). Anuário Brasileiro de Segurança Pública 2020. Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública https://forumseguranca.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/anuario-2020-final-100221.pdf.

Freyre, G. (2019). Casa-Grande & Senzala. Global Editora.

Goelitz, A. (2020). From trauma to healing: A social worker’s guide to working with survivors (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429001130

Henriques, J. G. (2018). Racismo no País dos Brancos Costumes. Tinta da China.

Heyman, J. C., & In Congress, E. P. (2018). Health and Social Work – Practice, Policy, and Research (1st ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

Iamamoto, M., & Carvalho, R. (1988). Relações sociais e serviço social no Brasil: esboço de uma interpretação histórico-metodológica (6th edition.). Cortez Editora.

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), Estudos e Pesquisas Informação Demográfica e Socioeconômica n.41 (2019). https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv101681_informativo.pdf

Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE), Resultados Provisórios dos Censos 2021. https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&indOcorrCod=0011170&xlang=pt

Kilomba, G. (2020). Memories of the Plantation – Episodes of everyday racism (2nd edition). Black Orpheus. https://www.ufrb.edu.br/ppgcom/images/MEMORIAS_DA_PLANTACAO_-_EPISODIOS_DE_RAC_1_GRADA.pdf

Lusa. (2021). Subsidiodependência degenera evolução do ser humano. Ventura apresenta nova lei para o RSI. Jornal I. https://ionline.sapo.pt/artigo/739081/subsidiodepend-ncia-degenera-evolucao-do-ser-humano-ventura-apresenta-nova-lei-para-o-rsi?seccao=Portugal_i

Martins, A. M. de C. (1995). Gênese, emergência e institucionalização do Serviço Social português. Intervenção Social, 11/12, 17–34. http://revistas.lis.ulusiada.pt/index.php/is/article/view/1265/pdf_1

Martins, A. P. de L. (2020). Do outro lado da intervenção: identidade e práticas profissionais dos pares no IN-Mouraria. Instituto Universitário de Lisboa. Iscte Repository. http://hdl.handle.net/10071/21049

Mate, D. G. (2018). In the realm of hungry ghosts. Vermilion.

Mortari, C. (2015). Introdução aos estudos Africanos e da diáspora. 1 (Ed) Florianópolis DIOESC:UDESC.

Moura, C. (1983). Escravidão, colonialismo, imperialismo e racismo. Afro-Asia, 14, 124-137. https://periodicos.ufba.br/index.php/afroasia/article/view/20824

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., … UnÜtzer, JÜ. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet, 392(10157), 1553-1598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. (2014)1st ed. SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. Available at: http://www.traumainformedcareproject.org/resources/SAMHSA%20TIC.pdf

Santos, B. S. (2003). Reconhececer para libertar: os caminhos do cosmopolitanismo multicultural. Civilização Brasileira.

Soulet, M-H. (2007). O Trabalho Social Paliativo: Entre redução de riscos e integração relativa. Cidades – Comunidades e Territórios, 15, 11-27. http://hdl.handle.net/10071/3448

Tatarsky, A. (1998). An integrative approach to harm reduction psychotherapy: A case of problem drinking secondary to depression. In Session: Psychotherapy in Practice, 4(1), 9-24. Available at:

Trevithick, P., (2012). Social work skills and knowledge: A practice handbook. (3rd Ed.) Open University Press.

WHO. (n.d.) Social determinants of health. www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1