Archives > Volume 19 (2022) > Issue 2 > Item 03

DOI: 10.55521/10-019-203

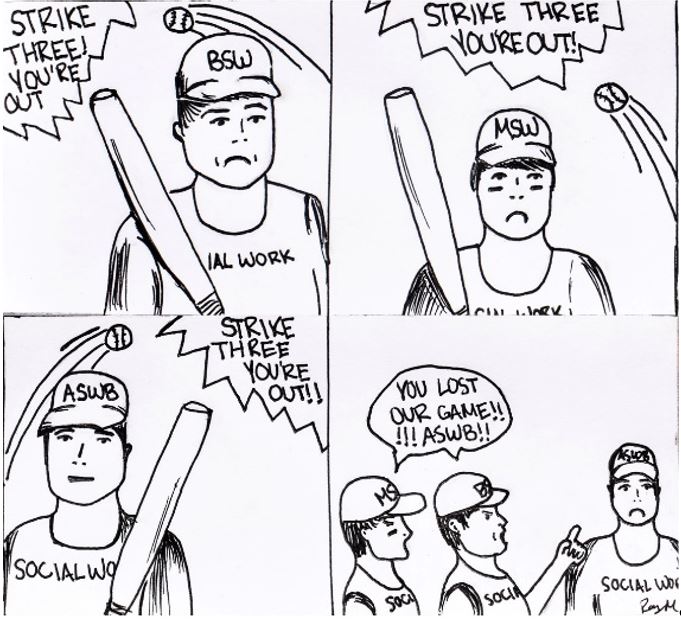

Stephen M. Marson, Ph.D., Editor, with artwork by Rachel Mathew, BSW/MSW Candidate and Board Member

Marson, S. (2022). Editorial: Does Racial Bias Exist in the ASWB Social Work Exams? International Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 19(2), 8-20. https://doi.org/ 10.55521/10-019-203

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of IFSW.

Today, the most paradoxical dimension existing in social work is institutional racism, embedded in everyday social work practice and education. It is paradoxical because of our official ethical principles which condemn the existence of racism and vigorously support social justice reform to eliminate racial bias in all its forms. Nevertheless, when we systematically assess our own institutional settings, we acknowledge the existence of latent institutional racism.

The Fundamentals of Institutional Racism within the Social Work Establishment

What is institutional racism? To answer this question, we must appreciate that institutional racism is a macro concept and originated within the sociological literature. The fountainhead for the existence of institutional racism emerged from Durkheim and Comte’s concept that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, and that social entities must be envisioned as an organic whole – a living organism. It exists because of the interaction of individuals, but the organism will continue to exist if an individual leaves the organic whole. Sociologists envision that social institutions are to a large degree independent from the individuals who are housed within the institution.

Merton (1949), a sociological functionalist, would label institutional racism as latent. That is, subconscious, not deliberate and not intentional. It is just the way we do things, and we don’t understand why, but most importantly we don’t think we need to understand why. In short, institutional racism includes discriminatory actions without conscious awareness. When racism is institutionalized, social workers honestly believe that they are acting and practicing in the best interest of their clients, but they are not. Marx wrote, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” That’s the problem with institutional racism – the lack of awareness behind and beyond awareness.

Is Institutional Racism Housed within the Social Work Establishment?

The simple answer to this question is YES! Social work, as a profession, has been profoundly criticized on many fronts. However, no one can accuse the profession of lacking introspection. If one depends on the literature, there is overwhelming evidence that institutional racism exists in social work education and social work practice. If one walked through the social work section in a library and a book fell off the shelf and hit your head, the book would be likely to include acknowledgement that institutional racism exists in social work. In less than 15 minutes, I immediately found the following references which acknowledged or analyzed institutional racism in social work:

Duhaney & El-Lahib (2021); Edmonds-Cady & Wingfield (2017); Gibbs (1971); Goggin, Werkmeister Rozas & Garran (2016); Grosser (1969); Hipple, Reid, Williams, Gomez, Peyton, & Wolcott (2021); Holley van Vleet (2006); Howitt & Owusu-Bempah (1990); Johnson, Archibald, Estreet & Morgan (2021); McMahon & Allen-Meares (1992); Mirelowitz (1979); O’Donohue (2016); Perez (2021); PTFS, (2007); Shannon (1970); Senreich & Dale (2021); Wright, Carr & Akkin (2021).

Five points can be made about these references:

- These articles do not assess institutional racism in society. Rather all the references address institutional racism within the profession of social work.

- This is not a comprehensive list. My computer search included references between 1901 and 2022. My citations include a nonrandom selection from a list retrieved from a computer search in an academic library.

- The oldest citation I could find was Grosser (1969).

- The search did not include books or chapters in books.

- Although I acquired a high volume of references, anyone who understands the algorithm of library search engines is aware that it is highly unlikely that all references could be pulled.

Conclusion? There is an enormous amount of introspection literature on institutional racism embedded in social work professional activities. Social workers do not deny that institutional racism exists within our own ranks.

A Sociological Intervention for Institutional Racism?

It is difficult to identify and nearly impossible to measure institutional racism. In reviewing the literature, I found confirmation that there is no universal tool to measure institutional racism (Adkins-Jackson et al., 2021). Frankly, without having a measurement scale, the problem of institutional racism cannot be successfully subjected to intervention. Institutional racism is a ghost that we can intuitively feel, but not assess or measure.

On the micro level, we find a wealth of measures which assess racial and ethnic attitudes starting in the 1890s. Although such measurements existed in the 1920s and 1930s, we acknowledge that the Holocaust was the catalyst for the explosion of attitude measures for every conceivable ethnic and racial group, as well as sexism as well as attitudes toward LGBTQIA populations. However, one of the most creative ideas comes from Project Implicit (https://www.projectimplicit.net). Project Implicit has a mission to assess attitudinal states that are subconscious and uncontrolled. Their measurements are currently being used for university students with a goal of a deeper self-understanding. These micro measures are well and good but fail to capture the essence of the macro dimensions embedded in institutional racism.

How Do BSW and MSW Programs Address Institutional Racism?

The primary method for confronting institutional racism in higher education is systematic recruitment for a diverse student body. Part of the accreditation process is presenting the diversity data of the student body. Academic programs are expected to have a diverse student body. If reasonable diversity among the student body does not exist, the academic program is expected to present plans to improve diversity. At this juncture in the history of accreditation, diversity is limited to race and gender and not populations like persons with disabilities and LGBTQIA communities. Is disregarding a population placed at risk a form of institutional bias?

Nevertheless, the systematic assurance that social work academic programs achieve racial diversity will not resolve the problem of institutional racism. By the definition addressed earlier, institutional racism is latently embedded in the group consciousness of faculty, students in general and students from historically marginalized groups. To eliminate institutional racism, it would take more than merely assuring human diversity among the student body and the faculty. Although every BSW and MSW program has a specific standard for admission, there are no quantifiable or universal admission standards. Thus, the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE), or any other outside objective observer, cannot assess the degree to which institutional racism impacts social work education. Failure of CSWE to take a leadership role in this arena is problematic.

My comment related to advocating for a systematic methodology for the admissions process will perhaps drive CSWE and administrators of academic programs to the brink of voluntary admissions to a psychiatric facility. However, the solution to institutional racism does not have to be extreme or dictatorial. During the reaccreditation cycle, program administrators could be required to address the question: “How does the program inhibit institutional racism within the admissions process?” AND I know exactly what will happen. Throngs of faculty members will publish blind refereed journal articles dissecting the issues and making recommendations. The group from BPD will formulate an instrument to assess institutional racism. Grant funding is likely to emerge. ASWB is likely to fund such research. Initially the instrument will demonstrate weak reliability and validity, but with the progression of time, the instrument will improve and be employed internationally. At any rate, that’s the normal response to changes in CSWE standards.

Admissions to both BSW and MSW programs is a critical component of combating institutional racism. Embedded within the concept of institutional racism is the acknowledgement that historically marginalized or populations placed at risk is not competing on a level playing field. Attending weak[1] high schools can prepare a student to be successfully admitted and successfully pass classes. However, the competition after graduation is another matter. Outside of the efforts to create diversity, the center problem with academic settings is the total lack of quantifiable efforts to address institutional racism. This lack of assessment handicaps faculty from identifying remedial academic exercises that would enhance a student’s critical thinking skills to be a more competitive professional. Simply stated, there are no efforts to measure or assess the embedded nature of institutional racism in the academic setting.

ASWB and Racial Test Bias

Unlike in the academic setting, ASWB has always employed highly quantitative strategies to address institutional racism. Marson, DeAngelis, and Mittal (2010) describe the statistical process with item analysis. That is, after a test item or question is systematically developed, screened by a committee of experts, and copy edited, a large sample of those answering the question is collected. The sample includes those social workers who are eligible to take the test. The distribution of the correct and incorrect answer is statistically analyzed. A number of the test-takers’ dimensions are assessed, including sex and race. If a correct answer can be predicted on the basis of sex and/or race, the item is eliminated from publication on the test. To clarify, ASWB systematically prohibits the use of test items which discriminate on the basis of race or sex. We know that each single item does not racially discriminate. If we assure that each item does not discriminate, does that mean that the test does not discriminate? The answer to this question lies in what statisticians routinely label “Simpson’s paradox.” It is mathematically possible for the whole to be greater than the sum of the parts[2].

In terms of institutional racism, we see a formal, standardized, rigorous and sterile process to eliminate racial and sexual bias in all ASWB exams. However, we do not see a functional equivalent in the admissions and assessment phase of any academic program. ASWB accounts for institutional racism in hard statistics while academic programs employ subjective impressions to assure that racial bias is not part of the educational system. By the definition of institutional racism, we cannot be consciously aware of our own racial biases. In social work academic programs, I suspect that many students who genuinely require remedial assistance are not afforded such an opportunity. A Black/African American social work scholar once said to me:

“The most devastating form of racism is creating a lower standard for African American students.”

By his statement, he meant that, out of White guilt or some other social function, students who need remedial assistance are denied the help they need to be successful after graduation. Offering assistance seems racist, whereas not offering assistance seems racist. My colleague acknowledged that if his statement is true, we would see lower pass rates for Black/African American social workers on licensing exams.

There is one corollary related to the White guilt proposition. The uncomfortable truth about academic programs is that they are funded on the basis of “full time equivalencies.” Today’s universities employ a factory model for funding. One question becomes, “Would a dean or director admit a marginal or submarginal student to increase or stabilize funding?” This decision is not a serious problem. The problem is admitting marginal or submarginal students without providing them some remedial academic assistance. Without additional assistance, these students are set up to fail after they graduate. This is institutional racism at its worst.

There are several harsh criticisms of ASWB’s clinical exam as being racially biased (Albright & Thyer, 2010; Castex, Senreich, Phillips, Miller, & Mazza, 2019; Woodcock, 2016). However, more introspection is required. The literature is clear-cut – institutional racism exists in social work academic programs. To begin to address institutional racism, several fundamental issues must be examined:

- There are no systematic standards developed by CSWE to address the problem of institutional racism.

- CSWE has no mandate to provide special assistance for marginal students.

- Under these conditions, we would expect lower pass rates than we are currently witnessing.

Our cartoon illustrates the poignant nature of this observation.

These bullets and cartoon may appear that I am blaming CSWE for institutional racism housed in social work practice and education. I am not! CSWE can become the fountainhead for the solution. Institutional isms are both a national and international problem. If CSWE can provide the leadership to dissect the problem, the findings will have a ripple effect on other professional and governmental settings. There is no profession on earth that has the skills, knowledge, and passion to uncover the ghost that is known as institutional racism. Social work has all the structural components to conduct research to uncover a workable intervention strategy but does not appear to have the leadership to guide such an effort.

As illustrated in the baseball cartoon, BSW and MSW programs strike out and the ASWB exams follow the only possible path – striking out. Kim’s (2022) data analysis supports the baseball analogy. More poignantly, all social workers must be held responsible for the continuation of institutional racism. The blame thrust upon ASWB is as absurd as blaming CSWE and NASW for the existence of institutional racism. The real question must be “what organization is going to take the leadership role in spearheading the research to combat institutional racism?”

Summary

In the end, there are two opposing views to interpret the outcomes of the ASWB exams. The current dominant view is that the test is racially biased. The other vision is that the education establishment is doing an inadequate job in training non-White students to be successful after they graduate. We all agree that institutional racism exists in higher education. We cannot measure or assess it, but we know that the ghost is there. Sadly, the only method that higher education employs to address the institutional racism is recruiting a diverse student population and nothing else. For me, the lack of quantification within the social work education establishment suggests that the problem of passage rates for ASWB exams lies within higher education and is not a result of test bias. In the end, the conjecture of racial bias within the ASWB tests must be used as a catalyst for research and intervention for institutional racism. This research will have an international impact.

So, where can we start? Two simple steps, or fair pitches, can get the baseball rolling:

- Within this editorial, I noted that the only one strategy exists to address institutional racism in BSW and MSW programs. That is, faculty and student diversity. If you know of other strategies employed by CSWE, email them to smarson@nc.rr.com and I will make them public so others can benefit from your efforts. We need to do more than have a diverse faculty and student body.

- And then, what actions can be taken by the social work educational establishment itself to combat institutional racism in BSW and MSW programs? What specific standard or standards can be established to improve the situation? Email your ideas to smarson@nc.rr.com and I will make them public.

If you have an opposing view or would just like to comment, email me at smarson@nc.rr.com and your letter will be published in the next issue.

[1] In the US on the federal and state level, objective measures exist to assess the quality of high schools. Graduate school social work programs must admit these students with remediation. Suskind (1998) offers a case study that vividly illustrates how an extraordinary intelligent young man who attended a weak high school was not able to successfully compete with students who graduated from quality high schools. Institutional racism is the most fertile ground for academic failure. Institutional racism is insidious because it is latent, unseen, unquantifiable. It is a ghost.

[2] A detailed description and understanding of Simpson’s paradox is beyond the scope of this editorial. To grasp the concept embedded within Simpson’s paradox requires a fundamental understanding of statistical analysis. There are many YouTube videos that will assist in appreciating the consequences of Simpson’s paradox.

References

Adkins-Jackson, P.B., Legha, R.K., & Jones, K.A. (2021). How to measure racism in academic health centers. AMA Journal of Ethics, 23(2), E140-145. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2021.140

Albright, D. L., & Thyer, B. A. (2010). A test of the validity of the LCSW examination: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Social Work Research, 34(4), 229–234. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42659768

Castex, G., Senreich, E., Phillips, N. K., Miller, C. M., & Mazza, C. (2019). Microaggressions and racial privilege within the social work profession: The social work licensing examinations. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 28(2), 211-228. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2018.1555498

Duhaney, P., & El-Lahib, Y. (2021). The politics of resistance from within. Advances in Social Work, 21(2/3), 421–437. https://doi.org/10.18060/24471

Edmonds-Cady, C., & Wingfield, T. T. (2017). Social workers: agents of change or agents of oppression? Social Work Education, 36(4), 430-442.

Gibbs, I. L. (1971). Institutional racism in social welfare. Child Welfare, 50(10), 582–587.

Goggin, E., Werkmeister Rozas, L., & Garran, A. M. (2016). A case of mistaken identity: What happens when race is a factor. Journal of Social Work Practice, 30(4), 349–363.

Grosser, C. F. (1969). Changing theory and changing practice. Social Casework, 50(1), 16-21.

Hipple, E., Reid, L., Williams, S., Gomez, J., Peyton, C., & Wolcott, J. (2021a). Disrupting the pedagogy of hypocrisy. Advances in Social Work, 21(2/3), 460–480. https://doi.org/10.18060/24465

Holley, L. C., & van Vleet, R. K. (2006). Racism and classism in the youth justice system: perspectives of youth and staff. Journal of Poverty, 10(1), 45–67.

Howitt, D., & Owusu-Bempah, J. (1990). The pragmatics of institutional racism: Beyond words. Human Relations, 43(9), 885-899.

Johnson, N., Archibald, P., Estreet, A., & Morgan, A. (2021). The cost of being Black in social work practicum. Advances in Social Work, 21(2/3), 331-353.

Kim, J.J. (2022). Racial disparities in social workers’ licensing rates. Research on Social Work Practice, 32(4), 374-387.DOI: 10.1177/10497315211066907

McMahon, A., & Allen-Meares, P. (1992). Is social work racist? A content analysis of recent literature. Social Work, 37(6), 533–539.

Merton, R. (1949). Social theory and social structure. Free Press.

Mirelowitz, S. (1979). Implications of racism for social work practice. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 6(3), 297–312.

O’Donohue, W. T. (2016). Oppression, Privilege, bias, prejudice, and stereotyping: Problems in the APA code of ethics. Ethics & Behavior, 26(7), 527–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2015.1069191

Perez, E. N. (2021a). Faculty as a barrier to dismantling racism in social work education. Advances in Social Work, 21(2/3), 500–521. https://doi.org/10.18060/24178

PTFS (Presidential Task Force Subcommittee – Institutional Racism). (2007). Institutional racism & the social work profession: A call to action. NASW Press. Retrieved from: https://www.socialworkers.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=SWK1aR53FAk%3D&portalid=0

Shannon, B. E. (1970). Implications of White racism for social work practice. Social Casework, 51(3), 270-276.

Senreich, E., & Dale, T. (2021). Racial and age disparities in licensing rates among a sample of urban MSW graduates. Social Work, 66(1), 19–28. https://doi-org.proxy181.nclive.org/10.1093/sw/swaa045

Suskind, R. (1998). A hope in the unseen: An American odyssey from the inner city to the ivy league. Broadway Books.

Woodcock, R. (2016). Abuses and mysteries at the Association of Social Work Boards. Research on Social Work Practice, 26(2), 225–231. https://doi-org.proxy181.nclive.org/10.1177/1049731515574346

Wright, K.C., Carr, K.A. & Akkin, B.A. (2021). Whitewashing of social work history. Advances in Social Work, 21(2/3), 271-297.