Archives > Volume 21 (2024) > Issue 1 > Item 11

DOI: 10.55521/10-021-111

Laurene Clossey, PhD, LCSW

East Stroudsburg University

lclossey@esu.edu

Hanif Bey, DSW, LSW

East Stroudsburg University

hbey2@esu.edu

Michelle D. DiLauro, PhD, LCSW

East Stroudsburg University

mdilauro1@esu.edu

Taniko King-Jordan, DSW, LMSW

Our Lady of the Lake

Dr.Tanikokingjordan@gmail.com

David Rheinheimer, Ed.D

East Stroudsburg University

davidr@esu.edu

Clossey, L., Bey, H., DiLauro, M., King-Jordan, T. & Rheinheimer, D. (2024). Can the business-oriented higher education environment compromise the ethics of social work education? An exploratory study of faculty perceptions. International Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 21(1), 170-199. https://doi.org/10.55521/10-021-111

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of IFSW.

Abstract

Many scholars have decried the transformation of higher education into a business model which pressures academics to treat students as a consumer group that must be retained. This research explored how these pressures affect social work faculty’s perception of their ethical ability to prepare future practitioners academically. The study surveyed social work faculty in higher education social work programs located in the Northeastern states of the United States. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected. Results show that pressures to retain students are felt, but most faculty uphold their values and standards. This exploration of faculty perceptions of education has important ethical implications. Social work engages complex issues and serves vulnerable individuals, making quality education a salient ethical concern.

Keywords: Professional education, ethical concerns, higher education, education, professional competence

Introduction

Educational preparation for professional careers is essential to ensure that the future workforce is competent. Ensuring proficiency in future practitioners is a significant ethical concern for educators in social work. The ethics of social work professional education unfold in a rapidly shifting environment due to the global encroachment of neoliberal philosophy, a belief that business models are the best way to organize all social institutions, even public services. The resultant business way of operating a university, treats students as consumers, seeks to commercialize university research, and emphasizes profitability. In this context, students are seen as resource “inputs” that must be kept satisfied with the university “service” of teaching; they must be aggressively recruited and then retained to ensure the income they bring to the institution. Faculty are reduced to service professionals, pressured by institutions to retain and satisfy the “customer base.” This pressure conflicts with social work professional ethics to educate for social justice and the professional commitment to colleagues, society, and future clients to preparing quality professionals (NASW, 2021).

Reamer (2013) points out that our ethics as educators include a gatekeeping role assuring student suitability for professional-level practice. Educational gatekeeping unfolds in an ethical faculty/student relationship that focuses on mentoring, role modeling, and careful and responsible counseling out of students who cannot meet the educational standards (Otters, 2013). This study will explore faculty perceptions of how they educate social work students in a neoliberal context that results in a corporatization (Washburn, 2006) of higher education that construes students as consumers rather than as learners.

Literature Review

Higher education scholars in the United States have noted a crisis in higher education in recent years. These scholars and experts, along with journalists (Young, 2003; Arum & Roska, 2005; Hersh & Merrow, 2005; Cote & Allahar, 2007; Dew, 2012; Selingo, 2013; Rossi, 2014; Wright, 2014; Kostal et al., 2016), note that higher education has shifted towards a business model that focuses on profit through the assurance of recruitment and retention of paying “customers” who evaluate the “service” (teaching) they receive. Cote and Allahar (2007) lament the phenomena of the student “customer” rating professors and affecting tenure decisions, inadequate student K-12 academic preparation for higher education, student and faculty disengagement from the educational process, and grade inflation (Valen, 2003; Hersh & Merrow, 2005; Supiano, 2008; Dew, 2012; Wright, 2014; Kostel et al., 2018; Baglione & Smith, 2022).

The current business orientation focus of higher education is referred using various monickers. Famously, in 1993, Ritzer wrote the “McDonaldization of Society,” using the framework of Weber to articulate a society obsessed with capitalism and productivity. Everything in society, argues Ritzer (1993) consequently borrows aspects of the efficiency process of McDonalds in order to encourage consumption. This even extends to the education sector, leading writers to talk about the McDonaldization of Higher Education (Hayes et al., 2002). Some authors refer to this obsession with the commercialization of faculty research, subsequent loss of academic freedom, and emphasis on pleasing the consumer as corporatism (Washburn, 2006).

Whether one uses the term “business model,” “McDonaldization,” or “corporatism,” the prevailing philosophy that embraces the current trends of the university worldwide is neoliberalism. (Radice, 2013). Neoliberalism is a belief in the hegemony of the free market to provide the best means of social organization. It reifies the free market as the ultimate solution to providing the best means to organize everything, including the public sector. This agenda to promote competition in all aspects of social life was emphasized under Ronald Reagan in the 1980s in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom (Savage, 2017). Thatcher and Reagan felt the free market was essential to optimal social governance, and they pushed for privatizing public services like health and education by cutting government investment and transferring public responsibilities to private corporations (Savage, 2017).

The neoliberal philosophy is pervasive; even the person is considered an entity that possesses and promotes capital (Cannella & Koro-Ljungberg, 2017). Competition is central to neoliberalism. The philosophy itself is so ubiquitous that it feels normal and logical; it is so commonplace that it is accepted by many and therefore, often remains unquestioned. (Cannella & Koro-Ljungberg, 2017).

In higher education, neoliberalism focuses on “accountability,” creating a culture obsessed with measuring and auditing (Lincoln, 2011). Neoliberalism values the university’s research efforts in terms of whether it can be commercialized such that research products are licensed and patented (Garland, 2008). This commercialization of research products undermines the public good ideal of university research. Academic freedom becomes undermined by conflicts of interest when the research activities of higher education scholars are funded by corporations and the technical or knowledge products are patented and licensed for profit (Washburn, 2006).

The teaching endeavor is also undermined by neoliberalism. Shore (2010) argues that neoliberalism “proletarianizes” professors, with universities increasingly making money by relying on adjuncts who are paid less and who only have short-term contracts. The measurement focus on assuring productivity and profit extends specifically into teaching in the form of obsession with the consumerization of students. These consumers represent the institution’s income, and their satisfaction with the educational “service” becomes something the neoliberal corporate model is determined to assess to ensure profit. This focus undermines teaching authority and can also be seen as proletarianizing the professorate.

In order to gauge student satisfaction and make decisions regarding faculty promotion and tenure, student evaluations of faculty have become widely used tools (Miller & Seldin, 2014). However, research by Stroebe (2016) and Stroebe (2020) reveals that these evaluations do not align with effective teaching as measured by student learning outcomes. Moreover, some scholars argue that these evaluations may contribute to grade inflation, as faculty may feel compelled to prioritize student satisfaction due to its influence on administrative decisions related to tenure, promotion, and contract renewal (Schneider, 2013; Crumbley et al., 2012).

Rebmen et al. (2018) conducted a national exploratory study in the United States, of faculty opinion of the effect of student evaluations on their teaching. They found that faculty in their sample believed that providing academic challenges would make the course more complex, resulting in lower grades and poorer teaching evaluations. There is concern that the consequent grade inflation encouraged by the pressure to attain good student evaluations results in an unethical emphasis on student satisfaction above student learning (Crumbley et al., 2012).

Khinduka (2007) raises concerns about the neoliberally informed business model’s effect on social work education. By 2024, social work will be the fastest-growing practice profession in health and behavioral health (Browne et al., 2017). Kirk et al. (2009) document that the selectivity of social work graduate schools is low, with most private MSW programs admitting about 75% of all applicants and schools that are minimally selective admitting 97%. Significant grade inflation has also been documented in academia, including schools of social work (Copeland, 2008; Chen, 2018; Miller, 2014; Hall, 2022). Stolz et al. (2010) argue that low selectivity and grade inflation have potential ethical implications for social work education, which affects the profession’s responsibility to society.

Social work practitioners can only be licensed in the United States if they have the necessary knowledge to pass licensure exams (Thyer, 2011; Croaker et al., 2017; Zuchowski et al., 2019). When social work faculty fail to expect and encourage learning, students suffer. Graduates may not know enough to pass the licensure exam the first time the test is taken. Apgar (2022) reports that the United States’ Association of Social Work Board data shows that approximately 27 % of social workers in 2021 did not pass their licensure exams on their first try.

This research explores United States social work faculty perceptions of preparing students for professional-level practice. This exploration of faculty perceptions adds to the dialogue on engaging in effective teaching for a profession when higher education institutions, due to the encroachment of a worldwide neoliberal social agenda, are increasingly operating as businesses trying to attract and retain a customer base. The current higher education context has ramifications for the quality of education and the teaching and learning process in social work. The quality of educational preparation for practice is ethically crucial for a profession that engages in complex issues and serves individuals in vulnerable circumstances. Being pressured to retain students and pushing along students admitted without adequate screening compromises social work ethics to educate for social justice, and maintain the obligation to society, the profession, and future clients, to gatekeep for professional suitability. This research explores whether social work faculty feel the pressures of open admissions along with pressures to retain students. The research considers whether these pressures, if felt, exert an effect on faculty teaching and upholding of standards.

Methods

An electronic survey method was used to collect data for this research. The survey was developed to collect descriptive data regarding faculty perceptions of student abilities, social work programs’ academic policies, marketing pressures felt through student evaluations, and faculty attempts to maintain standards and provide academic challenges. The survey contained questions soliciting qualitative and quantitative data. The team developed items that possessed face validity since this exploratory study sought only respondent perceptions. No hypotheses were tested. Once the items were developed, social work faculty colleagues provided feedback to improve the overall survey. This pilot testing ensured face and content validity, which is adequate for exploratory work. Survey items collected demographic information and presented a Likert Scale of 11 questions to assess perceptions of teaching, university pressures, and student abilities. A reliability analysis conducted on the 11 Likert Scale items after the survey administration, showed a Cronbach’s alpha of .86 for these 11 items.

The final survey contained 25 items. All of them, except for the above noted 11 Likert Scale items, collected demographic information, such as whether respondents taught in public or private schools, whether faculty were tenure track or adjunct, and the school’s admissions selectivity for social work. The Likert Scale items tapped into faculty perceptions of their teaching, their perceptions of student skills, and their perceptions of institutional pressures affecting their evaluations of students. The survey ended with a question regarding whether respondents would like to share any comments about student academics that were not asked in the survey.

Participation in the survey was entirely voluntary, and respondents were not provided any incentives to participate. The survey link was distributed via email to potential participants. This research project obtained approval from the University Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects, overseen by the principal investigator’s university.

The research team developed a listing of all Council of Social Work Education (CSWE) accredited social work programs in the Northeast, Northwest, Southeast, Southwest, and Midwest United States. The researchers felt it would be onerous to sample every region of the country, so one region was randomly selected. The Northeast (states on the East Coast from Maine to Maryland) was selected. Research team members visited the school websites to obtain social work faculty email addresses, acquiring 2,000 addresses. A purposive sampling method was used.

Each potential respondent received an emailed explanation of the survey, and informed consent was given upon opening the survey link. The link was emailed every three months with a solicitation encouragement until no new responses were received. At that point, email solicitation ceased. The survey remained open for approximately one year.

Some email addresses were undeliverable, and some faculty responded to inform us they were no longer teaching and would not be answering the survey. The research team estimated that the final survey was sent to about 1800 faculty. Four hundred and twenty-nine surveys were received, providing an estimated response rate of 24%.

Data Analysis

The overall study used a mixed methods approach. Data were exported from the electronic survey into SPSS 28 (IBM, 2021) software. Descriptive data were assessed, and some patterns were sought in that descriptive material. A final question asked if there was anything respondents would like to share about student academics. The narrative material yielded 109 individual responses that could be organized into themes.

Quantitative analyses include the presentation of descriptive statistics and chi-square analyses, and t-tests. Chi-square analysis uses a Pearson chi-square test to investigate possible associations between categorical variables, such as frequency of occurrence. Chi-square analyses were used to determine if associations existed between the perception that a student graduated with academic difficulties and a school’s admission selectivity. The same analysis was performed to assess whether there was an association between the belief that a student graduated with academic difficulties and the perception that not all faculty enforce academic policies uniformly.

Finally, independent t-tests were conducted to explore possible differences between graduate and undergraduate instructors in answers to questions about faculty perceptions of their teaching, student academic abilities, and institutional pressures affecting their evaluation of students. The Likert scale section of the survey was divided into three factors for analysis. The first factor, or dimension, was identified as faculty perceptions of upholding their standards and consisted of items one, two, and seven of the Likert scale questions. The second factor, or dimension, was identified as faculty perception of student abilities and consisted of items three, four, and five. The third factor, or dimension, was identified as the institutional pressures that faculty perceive and consisted of items six, eight, nine, ten, and eleven. The independent variable used for this analysis was the type of social work program (graduate/undergraduate). The dependent variable was faculty impressions of whether they were upholding their standards, perceptions of student ability, and institutional pressures.

Factor scores for each of the dimensions were calculated by summing the scores associated with the items for each factor for each participant and calculating the means of these sums. These factor scores were averaged over all participants to give the three dependent variables: faculty perceptions of upholding their standards (Factor A), faculty perception of student abilities (Factor B), and institutional pressures that faculty perceive (Factor C). Parametric tests are appropriate for analyzing these factors because the three factors are composed of a series of four or more Likert-type items combined into a single composite score/variable during the data analysis process (Boone & Boone, 2012). If item scores and item means are summed over all of the respondents’ items, and if the summed data and summed item means exhibit characteristics of a normal distribution, then both the summed data and item means can be considered interval/ratio data. Therefore, parametric statistical procedures can be used for data analyses.

Before creating the factor scores, nine of the eleven survey items were reverse scored so that all the items and factor scores would be on the same metric, whereby high scores would represent positive results. The items that were reversed scored were three to eleven.

A new independent variable was constructed based on the survey question, “In which social work programs do you teach?” This variable aimed to explore potential distinctions between graduate and undergraduate social work program instructors. The five response options were recoded as follows: BSW = 0, MSW = 1, BSW and MSW = 1, MSW and Doctoral Level = 1, All levels (BSW, MSW, and Doctoral) = 1, and Ph.D./DSW = 1. In this recoding scheme, 0 represents undergraduate teaching, and 1 represents graduate teaching. The resulting variable, T Level, had a frequency count of 92 faculty members teaching undergraduates and 334 teaching graduate students. This allowed for independent t-tests to examine if there were distinct response patterns between faculty teaching undergraduates and those teaching graduate students.

In addition to the quantitative data, the survey asked an open-ended question regarding whether respondents would like to add anything more about student academics. The resultant narrative responses were carefully read to assess for themes. The analysis utilized the process articulated in Strauss’s (2010) classic text on qualitative research entitled “Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists.” The steps to follow his process included organizing the data into themes (called open coding). The research team then reviewed these themes to collapse them further by noting and pooling themes that seemed related (axial coding). The team discussed the data until all members agreed on what core themes the data seemed to illustrate.

Results

Demographic data showed that 39.9% of respondents were tenured, 19% were tenure-track, and 25% were adjuncts. A few respondents selected “other” and were given the option to describe their faculty status. Answers included clinical faculty, research faculty, and field director. Of the 17% selecting “other,” many identified as assistant or associate professors, indicating they were, in fact, tenure track rather than other. Most of this sample (56%) taught in public universities, and 44% taught in MSW programs

A total of 96% of respondents had their highest degree in social work, 2% possessed their highest degree in psychology, 2% had their highest degree in sociology, and .25% had a counseling degree. Some respondents indicated that their highest degree was in another field. Respondents who selected “other” could identify their field. Answers included public health, medicine, education, human development, developmental science, social welfare, and family studies.

Respondents were asked to rank their programs on admissions selectivity. Respondents could rank a program between 1-10, with 0 being “not at all selective” and ten indicating “highly selective.” These rankings were collapsed into categories. Programs rated 1-4 were labeled “minimally selective,” programs rated five were considered “moderately selective,” and six and above ratings were considered “highly selective.”

Respondents were asked, “Have you ever believed that your university/department graduated a student with serious academic weaknesses (e.g., the inability to write coherently, comprehend research, engage in critical thinking, lack of basic quantitative reasoning abilities) that would make it difficult for that student to practice professionally?” Most respondents, 75%, answered “yes.” This basic yes/no answer will inevitably result in a good number of “yes” answers and so a series of Likert scaled questions explored these perceptions in more depth. Ninety-six percent of respondents noted that their programs had academic policies, and 51% felt these policies needed to be uniformly enforced by all faculty. Seventy-seven percent of respondents felt student evaluations weighed heavily in tenure/promotion decisions, yet 63% maintained that this issue did not impact their grading.

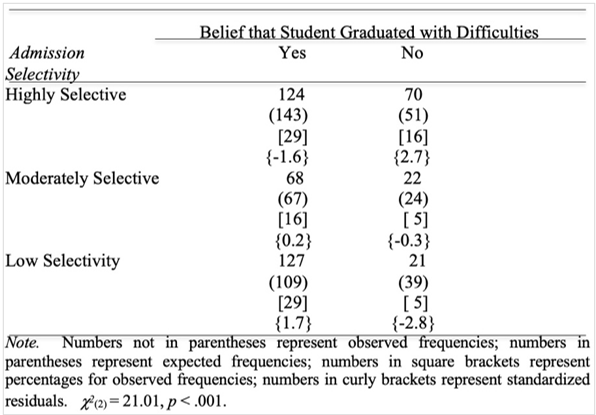

Table 1 is a contingency table for the cross-tabulation between the belief that a student graduated with academic difficulties and school admission selectivity. Table 1 shows a significant association (p < .001) between the belief that a student graduated with academic difficulties and school admission selectivity. Thus, the belief that a student graduated with academic difficulties was not independent of a school’s admission selectivity. In addition to the observed frequencies for each cell of Table 1, the expected frequencies, the percentages of the total for the observed frequencies, and the standardized residuals for each cell are also given. Standardized residuals are used to evaluate each cell’s contribution to the overall significance of the analysis. A standardized residual greater than 1.96 or less than -1.96 indicates a cell’s outsized contribution to the association between the two study variables.

In Table 1, two standardized residuals were greater than 1.96 or smaller than -1.96. These residuals were for the cell for “Highly Selective’” for admission selectivity and “No” for the belief that a student graduated with academic difficulties, and the cell for “Low Selectivity” and “No” for the belief that a student graduated with academic difficulties. In addition, the cell for “Highly Selective” for admission selectivity and “Yes” for the belief that a student graduated with academic difficulties, and “Low Selectivity” and “Yes” for the belief that a student graduated with academic difficulties had standardized residuals that were very near the critical values of 1.96 and -1.96. These four cells had the most significant impact on the overall significance of Table 1. Comparing the expected and observed frequencies within these critical cells reveals that when admission selectivity was high, more faculty than expected did not believe that a student graduated with academic difficulties. Alternatively, when Admission Selectivity was low, fewer faculty than expected did not believe that a student graduated with academic difficulties. Admission selectivity may have impacted the belief that a student graduated with academic difficulty.

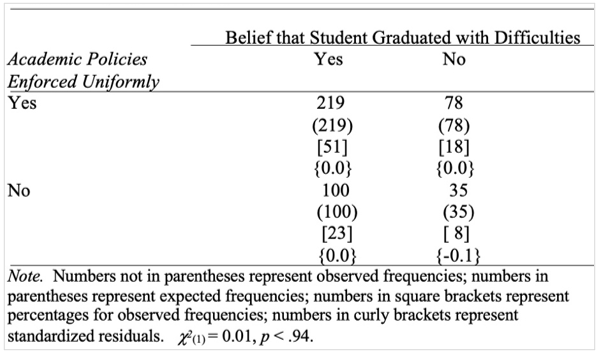

Table 2 is a contingency table for the cross-tabulation between the belief that a student graduated with academic difficulties and the perception that not all faculty enforce academic policies uniformly. A chi-square analysis was performed to determine if an association existed between these two variables. Table 2 shows no significant association (p < .941) between the perception that a student graduated with academic difficulties and the perception that not all faculty enforce academic policies uniformly. Thus, faculty who believed that students had graduated with academic difficulties were as likely to believe that academic policies were enforced uniformly as to believe that they were not. In addition to the observed frequencies for each cell of Table 2, the expected frequencies, the percentages of the total for the observed frequencies, and the standardized residuals for each cell are also given. All of the standardized residuals in Table 2 were far from the critical criteria cited above, reaffirming the lack of significance found for this table.

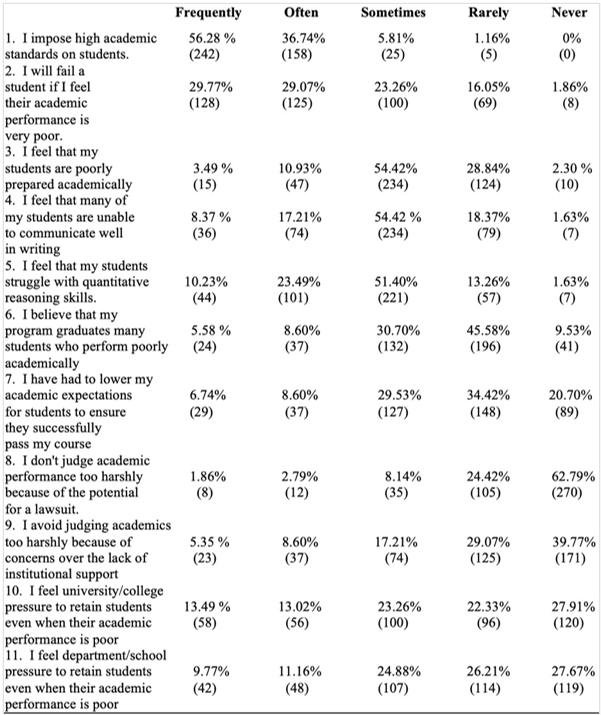

Table 3 displays answers to 11 Likert scale questions regarding faculty perception of student academic performance, their teaching, and institutional pressures affecting their evaluation of students. The table shows that 93% of all respondents either frequently or often believe they impose high academic standards. The majority (59%) report that they will fail a student whose academic performance is poor. However, 41% report that they will sometimes, rarely, or never fail a poorly performing student. When it comes to this sample’s perception of their student’s performance, half or more endorse “sometimes” to the items assessing their feeling that students are poorly prepared academically, unable to communicate well in writing, and unable to engage in quantitative reasoning. While there is a sense of students struggling, most (55%) respondents rarely or never feel that their programs graduate poorly performing students. Sixty-eight percent of respondents felt they were not institutionally pressured regarding their grading, and 87% of respondents rarely or never felt they were impeded from judging academics over potential lawsuits.

Regarding institutional pressures, most respondents (54% ) rarely or never feel department pressure to retain poorly performing students. Similarly, 50% rarely or never feel university pressure to retain poorly performing students. Yet, 26 % of respondents always or often feel this university pressure while 25 % feel it only sometimes.

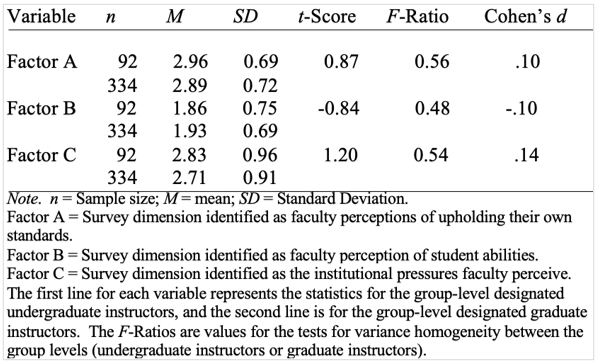

Independent t-tests were then conducted to explore possible differences between graduate and undergraduate instructors on the three factors from the survey (Table 4). Because the factor scores were highly correlated and we were making repeated tests of the same procedure, the Bonferroni Correction was applied to the overall alpha level (.05) to reduce the risk of making a Type I error. This correction was accomplished by dividing the alpha level by the number of t-tests to be conducted (three), resulting in a new alpha level of .017 (.05/3). Table 4 shows no significant differences between graduate and undergraduate instructors for any of the three-factor scores.

One hundred and eighty-six respondents answered an open-ended question inquiring whether there was anything about student academic preparedness and ability that respondents would like to add. Several comments were “no,” “thank you,” “great survey,” or “bad survey.” Some of them were simply notes on how to improve the research. Once these were deleted, there were 162 comments left. Of those, 109 contained remarks that could be organized thematically by following Strauss’ (2010) process described above in the data analysis section. These comments were coded into five themes: academic readiness and importance of academics, money and marketing concerns, student challenges, Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS), and innovative pedagogy. Each of the 109 comments comes from a different respondent.

Fifty-six comments organized into the theme of academic readiness and the importance of academics indicated that faculty must consistently assess academics once students are accepted into social work programs. Some illustrative remarks are reproduced:

I believe the ability to apply academic knowledge to practice situations effectively is the single most important strength we cultivate as social work faculty.

However, some respondents noted there is debate about the importance of mastery of basic grammar, reading, and writing skills, and the ability to read academic texts.

There is debate in the field about how much academic performance really predicts professional success, especially for students going into direct practice. Can a student who writes poorly still engage clients and help them achieve their personal goals?

Other responses that fit this theme noted the importance of a challenging education for professional social work practice.

I think it’s important to have high standards and strong and robust student supports of all kinds.

Two respondents expressed concern that emphasizing academics would reproduce racism and a Eurocentric point of view. One wondered how the phrase “writing well” should be defined. Does it mean “white English?” Another respondent worried that the term “academic rigor” may be promoting racism since a historical impact of that term was to deliberately exclude students of color. Rigor may often be misunderstood as burdening students with additional or more challenging work. However, the academic challenge is essential to growth in many personal and cognitive areas. Since rigor can be misunderstood as undermining social justice, another way of explicating academic challenge should be considered.

I don’t think academic achievement always equates to a student being a good social worker.

Critical thinking is a cognitive process that requires making sound, ethical decisions through reasoned discernment, appraising, and integrating multiple sources of knowledge (Mathias, 2015). Critical thinking demands active learning by challenging previously held assumptions through serious examination (Brookfield, 2017). Social work encourages and engages students to broaden their thinking skills and to probe deeply into solving problems. Those cognitive processes necessitate challenging academics.

Innovative teaching that promotes critical thinking skills in a supportive and inclusive manner appears essential to the respondents in this study. Ninety-one percent of respondents believed the academic expectations for social work should be rigorous. The following perceptions from three respondents underscore the significance of critical thinking and academic challenge in social work education:

Rigor is crucial in our profession. Social workers make decisions every day, and they need to be critical thinkers. I believe as social work educators, we need to teach these skills to support their development.

In my teaching experience, interpersonal skills/emotional readiness have been much more of an issue in gatekeeping. They are harder to evaluate and harder to address. But academic issues are relevant as well, and the largest within that has been writing ability. Occasionally, critical thinking.

I feel there are two problems. 1. Many courses are not rigorous in their demands/expectations of the students & the assignments, etc., e.g., a clinical course may have most assignments as reflections rather than assignments that require students to think critically. 2. Many faculty do not take grading seriously. They do not review for grammar, organization, etc. If the student has at least written at least something, they seem to get a good grade. Moreover, these same faculty do not provide constructive feedback to students so they can improve their skills. I have had many students say to me that I am the first faculty member who has given them detailed feedback on their papers. I get students in the advanced year who can’t even conduct a literature review, let alone write this up in any organized way.

Lastly, some respondents felt academic standards were compromised by a lack of faculty consistency in applying them. The quantitative results noted a perception among 75% of the sample that their programs were graduating students with academic weaknesses that would make practice difficult. However, most faculty in the sample felt they were not simply pushing their students through their programs. Instead, the perception of 52 % was that other faculty needed to be more consistent. A few comments illustrate this:

The lack of consistency of expectations & grading across faculty results in mixed messages & confusion for students and puts instructors who try to uphold standards at a significant disadvantage.

Consistency in faculty practice & skills within the programs. Huge variability in grading & their expectations sends highly mixed messages, which is unfair to both students & faculty & also impacts evaluations.

Thirty-three respondents mentioned that enrollment and retention pressures affect academic assessment. These comments were organized under the theme money and marketing concerns. None of the respondents’ comments indicated these pressures were positive; all respondents saw these as driving down faculty autonomy to evaluate students objectively. Some typical remarks are presented below:

The game is rigged. So long as tenure decisions or contract renewals for adjuncts are based even in part on student evaluations, there is a disincentive to grade rigorously—those faculty who do usually get poor student ratings.

Enrollment pressure is related to the university budget.

I feel a great reluctance from the school to remove or fail any students.

It is a very sad state of graduate education. School admits almost anyone to meet enrollment goals & make $$. Then complicit in graduating nearly everyone regardless of academic performance. Virtually no effort to make sure students are minimally competent on all levels.

The narrative data contained comments about faculty worries regarding students’ mental health and emotional challenges. Approximately 16 respondents noted these issues in a theme labeled “student challenges.” Some of these comments expressed concern about providing appropriate remediation and student support. A few respondents wondered if students could practice effectively without remediating issues interfering with professionalism and boundaries. An example is reproduced below:

I have seen a significant decline in the emotional maturity and the commitment of the social work graduate students admitted to the program.

Four comments remained. Three were complaints about the Council of Social Work Education’s Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards. These were organized under the theme, CSWE EPAS. The complaints about CSWE represented opinions that problems with education were due to the accrediting body’s failure to allow for assessments that could be more objective and overcome institutional pressures to pass students along. There was one comment about the need to be innovative in distance education modalities due to COVID.

Discussion

This study assessed United States’ social work faculty’s perception of student ability, their teaching, and institutional pressures affecting faculty evaluation of students. Overall, a substantial percentage of faculty in this sample noted that their programs graduated at least some unprepared students. This perception occurred more often when an institution with low student selectivity for program admission employed the responding faculty.

The sample reported on in this study, revealed that 84% of faculty respondents reported they sometimes, rarely, or never lowered their expectations for students to complete coursework. The findings of this research are consistent with the results of Rebman et al. (2018), who conducted a nationwide survey of higher education faculty to assess faculty opinions of student readiness for college, their academic performance, and the effect that student evaluations had on teaching. They found that while faculty in their sample believed that assigning higher grades and making content easier would result in better student evaluations, few faculty felt themselves giving into that pressure to lower their standards. In this study’s sample, about 26 % always or often felt institutional pressure to pass students along and 25% felt it sometimes. This represents a minority, with about 54 % reporting not feeling institutional pressure to pass students.

While most faculty in this sample report never lowering their standards, 30% reported they sometimes felt they did lower standards to assist a student in passing their courses. This indicates that some faculty consciously perceive that they “push” students along.

Results showed that a substantial majority of faculty stated that they frequently (56%) or often (36%) imposed high academic standards on students. However, 41% of respondents reported that they only sometimes, rarely, or never failed poorly performing students. Despite this, most respondents felt they were promoting high academic standards, but most felt their colleagues needed to be promoting the same.

Few respondents in this sample felt university pressures in the form of fear of lawsuits for judging academics too harshly, lack of institutional support for their grading, or department or university pressures to retain students. However, when it came to feeling students were poorly prepared academically, 54% felt that was sometimes an issue. Similar percentages were found for the “sometimes” answer regarding student struggles with quantitative reasoning and the ability to write well. Very few faculties felt these student issues were frequently or often a problem.

The qualitative results add to the quantitative findings. The narrative responses indicate that faculty want to offer high standards, but 53 comments emphasized constraints on academic standards imposed by needing to retain students and the pressures of student evaluations. Some respondents may have felt the impact of open admissions and retention pressures as evidenced by comments about needing to support students once they were admitted. Thus, while unable to screen students for entry, once students were in the program, faculty wanted to assure the supports needed for their success were available.

While the quantitative findings show that most respondents do not allow university pressures to affect grading, the narrative comments illustrate the perceptions of those who feel institutional pressures. Those who do not allow those pressures to affect grading may feel them but not allow them to have an impact. Respondents in this sample expressed worry about marketing pressures, manifesting as an emphasis on results of student evaluations of teaching for tenure and promotion decisions and emphasis by the administration on student retention. Although the narrative material indicated that faculty in this sample felt these pressures, they also felt the desire to be socially just and help students succeed.

Study respondents mostly report wanting the profession to produce knowledgeable and competent practitioners. The respondents struggle with promoting critical thinking and communicating well in writing without reproducing a Eurocentric perspective. They wanted students to be screened better but did not want to be too harsh. Some comments articulated concern that better screening would result in students with some hidden strengths not being acknowledged. The results reflect the felt pressures of the business model driving higher education along with unique social work concerns about how to educate for a profession in a just and equitable manner. This dilemma indicates an ethical struggle that faculty in this sample strive to resolve.

Limitations

The data of this study are limited by the exploratory nature of the research and the consequent use of a survey tool that could only be psychometrically assessed for face and content validity. The results can only be understood as exploring a phenomenon with a limited sample, and the results should not be considered generalizable to the experience of all faculty in schools of social work. In addition, only respondents in a limited geographical region were surveyed, the response rate needed to be higher, and there is no way of knowing whether those who answered significantly differed from those who did not. Other limitations include a failure to collect the race and ethnicity of respondents, which may have resulted in varying opinions about education rooted in culture. This should be explored in future research. There is also the chance that faculty who responded could have answered in a biased manner to present what they felt were socially desirable responses. If that were a potential bias, it might have led many to deny that institutional pressures affected their pedagogy and assessment of students. Finally, the survey itself was very basic. It was not rigorously tested psychometrically to measure a phenomenon or prove a hypothesis. It was developed for face and content validity, so there was concern about a lack of rigor that could account for spurious variables.

Conclusions

In summary, this exploratory work showed that most faculty in this sample did not feel that students were poorly prepared or that they allowed institutional pressures to impact them to grade leniently. Most respondents (54 %) did not feel a pressure to pass students along. However, about one quarter of the sample did feel that they often or always (26 %) felt university pressure to pass students along and another quarter (25 %) felt that pressure only sometimes. Overall, in this sample, faculty care about being socially just and fair educators. Most respondents feel very committed to a challenging education that prepares students for professional practice.

Social work students deserve a quality education that assuages a desire to learn and prepares them for competent social work practice. In an era where neoliberalism has colleges marketing for prestige and public institutions of higher education experiencing state reductions in higher education investment, students today are increasingly engaged in a “paper chase” for an expensive degree that places them in debt for many years (Bunch, 2022). This steers the emphasis away from pursuing knowledge as an end and onto the “purchase” of a degree as a means to a job. Social work students and their future clients deserve better than that. Social work faculty in this sample maintain their ethics to teach and to prepare their students for professional practice in the context of colleges run as businesses that emphasize student retention and satisfaction over measures of actual learning.

References

Apgar, D. (2022). Linking social work licensure examination pass rates to accreditation: The merits, challenges, and implications for social work learning. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 42(4), 335-353. DOI: 10.1080/08841233.2022.2112809.

Arum, R., & Roksa, J. (2011). Academically adrift. University of Chicago Press.

Baglione, S.L., & Smith, Z. (2022) Grade inflation: undergraduate students’ perspective. Quality Assurance in Education, 30(20), 251-267. DOI. 10.1108/QAE-08-2021-0134.

Boone, H.N., Boone, D.A. (2012). Analyzing Likert Data. Journal of Extension [On-line], 50 (2), Article 2TOT2. http://www.joe.org/joe/2012april/tt2p.shtml

Brookfield, S. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Browne, T., Keefe, R., Ruth, B., Cox, H., Maramaldi, P., Risshel, C., & Marshall, J. (2017). Advancing social work education for health impact. American Journal of Public Health, 107(S3), S229-S235. https://doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304054.

Bunch, W. (2022). After the ivory tower falls. Harper Collins Publishers.

Cannella, G.S., & Koro-Ljungberg. (2017). Neoliberalism in Higher Education: Can we understand? Can we resist and survive? Can we become without neoliberalism?

Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies, 8 pages. https://doi:10.117/1532708617706117

Chen, R.K., (2018) Determinants of course grades in allied health sciences. Journal of Allied Health, 47(1), 35-44. PMID: 29504018.

Copeland, S. (2018). BPD president’s address to the 2015 annual conference: Gatekeeping for the future. The Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 23(1), 232-235. https://doi.org/10.18084/1084-7219.23.1.231

Cote, J., & Allahar, A.L. (2007). Ivory tower blues. University of Toronto Press.

Croaker, S., Dickinson T., Watson, S., & Zuchowski, I. (2017). Students’ suitability for social work: Developing a framework for field education. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 19(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol31iss2id633

Crumbley, L.D., Flinn, R., & Reichelt, K.J. (2012). Unethical and deadly symbiosis in higher education. Accounting Education: An International Journal, 21(3), 307-318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2012.667283.

Dew, J.R. (2012). The Future of American Higher Education. World Future Review, Winter, 7-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/194675671200400403

Garland, C. (2008). The Mcdonaldization of higher education?: Notes on the U.K. experience. Fast Capitalism, 4 (1), 107-110. https://doi.10.32855/fcapital.200801.011

Hall, R.E. (2022). Grade inflation investigation: Ethical challenges to the social work academy. Social Work Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2063829

Hayes, D., Wynyard, R., & Mandal, L.(([2002] 2017). The McDonaldization of Higher Education, Retrieved 8/9/2023 from: https://repository.derby.ac.uk/item/953wq/the-mcdonaldization-of-higher-education

Hersh, R.H. & Merrow, J. (2005). Declining by degrees. St. Martin’s Griffin.

IBM Corp.(2016.). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. IBM Corporation.

Khinduka, S.K. (2007). Toward rigor and relevance in U.S. social work education. Australian Social Work, 60(1), 18-28.

Kirk, S.A., Kil, H.J., & Corcoran, K. (2013). Picky, picky, picky: Ranking graduate schools of social work by student selectivity. Journal of Social Work Education 45(1), 65-87. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2009.200700088

Kostal, J.W., Kuncel, N.R., & Sackett, P.R. (2016). Grade inflation marches on: Grade increases from the 1990s to 2000s. Educational Management: Issues and Practice, 35(1), 11-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12077

Lincoln, Y.S. (2011). “A well-regulated faculty…:” The coerciveness of accountability and other measures that abridge faculties’ right to teach and research. Cultural Studies Critical methodologies 11 (4), 369–372. https://doi.10.1177/53270861141668

Mathias, J. (2015). Thinking like a social worker: Examining the meaning of critical thinking in social work. Journal of Social Work Education, 51(3), 457-474. https://doi.org/10/1080/10437797.2015.1043196

Miller, G. (2014). Grade inflation, gatekeeping, and social work education: Ethics and perils. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 11(1), 12-22.

Miller, E.J., & Seldin, P. (May/June 2014). Changing practices in faculty evaluation: Can better evaluation make a difference? American Association of University Professors. Retrieved 5/23/2023 from: https://www.aaup.org/article/changing-practices-faculty-evaluation

National Association of Social Workers (2022). NASW Code of Ethics. Retrieved 8/10/2023 from: https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

Otters, R.V. (2013). Social work education: Systemic ethical implications. Journal of Social Work Values and ethics, 10 (2), 58 – 69. Retrieved 8/7/2023 from: https://www.jswve.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/10-010-209-JSWVE-2013.pdf

Radice, H. (2013). How we got here: U.K. Higher Education under neoliberalism. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographics, 12 (3), 407-418. Retrieved 8/9/2023 from: https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/969

Reamer, F.G. (2013) Distance and online social work education: novel ethical challenges. Journal of Teaching in Social work, 33, 369-384. Retrieved 8/7/2023 from: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/facultypublications/392.

Rebman, C.M., Wimmer, H., & Booker, Q.E. (2018). A nationwide exploratory study on faculty opinions on student preparation, performance, and evaluations. Proceedings of the EDSIG Conference. Norfolk, Virginia, USA.

Ritzer, G. (1993). The mcdonaldization of society. Sage Publications.

Rossi, A. (2014, May 22). How American universities turned into corporations. Time. https://time.com/108311/how-american-universities-are-ripping-off-your-education

Savage, G.C. (2017). Neoliberalism, education and curriculum. Retrieved 8/8/2023 from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Glenn-Savage/publication/320069681_Neoliberalism_education_and_curriculum/links/59cc4808aca272bb050c6a7e/Neoliberalism-education-and-curriculum.pdf

Schneider, G. (2013). Student evaluations, grade inflation, and pluralistic teaching: Moving from customer satisfaction to student learning and critical thinking. Forum for Social Economics, 42(1), 122-135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07360932.2013.771128.

Selingo, J.L. (2013). College unbound: The future of higher education. Amazon Publishing.

Shore, C. (2010). Beyond the multiversity: neoliberalism and the rise of the schizophrenic university. Social Anthropoligy/Anthropologie Sociale, 18 (1), 15-29. https://doi.10.1111/j.1469-8676.2009.0094.x

Stoesz, D., Karger, H.J., & Carillio, T. (2010). A dream deferred: How social work education lost its way and what can be done. Transaction Publishers.

Strauss, A. L. (2010). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press.

Stroebe, W. (2016). Why good teaching evaluations may reward bad teaching: On grade inflation and other unintended consequences of student evaluations. Perspectives on Psychological Science,11 (6), 800-816. DOI:10.1177/1745691616650284.

Stroebe, W. (2020). Student evaluations of teaching encourages poor teaching and contributes to grade inflation: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 42(4), 276-294. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2020.1756817

Supiano, B. (2020). The real problem with grade inflation. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-real-problem-with-grade-inflation

Thyer, B.A. (2011). LCSW examination pass rates: Implications for social work education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 39, 296-300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-009-0253-x

Valen, J. (2003). Grade inflation: A crisis in college education. Springer Publications.

Washburn, J. (2006). University inc.: The corporate corruption of higher education. Basic Books.

Wright, R.E. (2014). Student-focused marketing: Impact of marketing higher education based on student data and input. College Student Journal, 48(1), 88-93. http://essential.metapress.com.proxyesu.klnpa.org/link.asp?target=contribution&id=82403634538J6687

Young, C. (2003). Grade inflation in higher education. ERIC Digest (ED482558). www.eric.gov.

Zuchowski, I., Watson, S., Dickinson, T., Thomas, N., & Croaker, S. (2019). Social work students’ feedback about students’ suitability for field education and the profession. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work Review, 31 (2), 42-56. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol31iss2id633