Archives > Volume 21 (2024) > Issue 1 > Item 08

DOI: 10.55521/10-021-108

Tamara Kincaid, PhD, LICSW

University of Wisconsin – River Falls

tamara.kincaid@uwrf.edu

Carl Brun, PhD, LISW, ACSW

Wright State University

carl.brun17@gmail.com

Brian Carnahan, MBA, MA

Ohio Counselor, Social Worker, and Marriage and Family Therapist Board

brian.carnahan@cswb.ohio.gov

Tiffany Welch, DSW, LSW

Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania

twelch@commonwealthu.edu

Darrin E. Wright, PhD, LMSW, MAC

Clark Atlanta University

dwright@cau.edu

Michelle Woods, LMSW

University of Michigan

micwoods@umich.edu

Dianna Cooper-Bolinskey, DHSc, MSW, LCSW, LCAC

Campbellsville University

drcooper@campbellsville.edu

Kincaid, T., Brun, C., Carnahan, B., Welch, T., Wright, D., Woods, M. & Cooper-Bolinskey, D. (2024). Seriousness of Social Worker Violations and Importance to Discipline: A Study of Social Work Licensure Board Members. International Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 21(1), 71-97. https://doi.org/10.55521/10-021-108

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of IFSW.

Abstract

This research explored social work licensure board members’ decision-making about alleged violations by social workers and subsequent sanctioning. Participants served within the last five years on a jurisdictional board regulating social workers in the US. The survey included factors related to board member decision-making, rank ordering the seriousness of listed allegations, and four vignettes where participants rated the seriousness of the allegations and the importance for a board to discipline the social worker. Persons serving on twelve US boards that license social workers (n=21) read four vignettes of hypothetical social worker violations and rated the seriousness of the violations and the importance of disciplining the social workers. The violations, in order from most (7) to least severe (1) were fraudulent record keeping (5.63), professional boundaries (non-sexual) (5.37), impairment (5.1), and improper termination (2.63). The importance to discipline, in order from most (7) to least important (1), were: professional boundaries (non-sexual) (6.1), fraudulent reporting (5.68), impairment (4.4), and improper termination (2.47). Having an MSW degree, as opposed to BSW, was the only variable increasing the seriousness of the offense in all four vignettes. Results may help with understanding how licensing boards review alleged violations and determine sanctions.

Keywords: Allegations, board member participants, importance, sanctions, seriousness

US jurisdictions regulate health care and social service providers to protect the public from potential harm. Regulation of social work practice began in Puerto Rico in 1934 and moved to the US in California in 1945 (Goodenough, 2021). It was not until 1992 that every US jurisdiction regulated social work practice (Cooper-Bolinskey, 2019). Once social work was fully regulated, it became important to understand the consequences for improper practice and how boards make these decisions. Unfortunately, to date, there has been little research on this topic. Results from the study being presented in this article explore board decision making from several perspectives. Participants were asked about board member training, rank ordering the seriousness of a list of practice violations, and then asked to review four vignettes and rate the seriousness of the social worker’s behavior as well as the importance to discipline. A brief discussion of the history of regulation is provided, first, in order to frame the context of the study.

Literature Review

Protecting Consumers from Harm by Social Workers

Social work began as a profession in the late 19th Century, initially addressing issues of poverty experienced by immigrants and other oppressed groups. As the profession grew, the Conference of Boards and Charities developed, followed by the National Conference of Charities and Correction, and in 1955 the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) was founded. NASW developed the professional Code of Ethics, which was identified as the gold standard of practice for social workers. Schools of social work developed during this same period, along with the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE), the accrediting body for social work education (Stuart, 2013). The Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB) emerged as the profession’s regulatory-focused organization in 1974, providing support and services to social work boards in the effort to ensure public protection and safe, ethical, and competent practice (CSWE, 2018).

The professional and educational growth of social work, along with a focus on addressing sensitive issues and assisting vulnerable people, led to the passing of laws for protecting the public and regulating social work practice. Through the advocacy of professional organizations, all US jurisdictions have enacted legislation to regulate social work practice (Cooper-Bolinskey, 2019). Some jurisdictions regulate by title protection, some by practice protection, and some use both. Jurisdictional regulatory boards are composed as either only social workers, or a composite board. Composite boards include other professions, for example, professional counselors or licensed marriage and family therapists.

In response to the variations in board composition, ASWB aimed to provide technical and advisory assistance to jurisdictional regulatory boards as they enforce practice regulation. ASWB also provided new board members with training about regulation and disciplinary procedures. In 1997, ASWB developed the Model Social Work Practice Act (MSWPA). The MSWPA served to define a practice standard to guide developing regulatory laws by defining such components as title protection, board structure, and requirements of practitioners (ASWB, 2022).

ASWB (2018) produced another regulation resource for social work board members, the Guidebook on Social Work Disciplinary Actions. The guidebook provided regulatory board members with a resource when deciding on license violations. It described a variety of violations reviewed by board members and types of disciplinary actions board members may consider in social work regulation.

There is little to no literature on how social work boards use these resources. There is also little information on what other sources are available to assist board members about making decisions when disciplining social workers who have had professional violations.

Board Regulation Research

Daley and Doughty (2007) noted that previous research on social worker professional violations was primarily based on records of reports of violations to NASW. Strom-Gottfried (2003) reported on NASW ethics committee reviews of social worker ethics violations complaints between 1986-1997. Daley and Doughty (2007) compared ethics complaints reported to NASW and violations reported to the Texas licensure board between 1995-2003.

The primary focus of social work regulation research has been on ethical violations, including the characteristics of individuals committing violations. Daley and Doughty (2007) focused on license type and level of education, while Boland-Prom (2009) offered insight into the entity disciplining the social worker. Magiste (2020) conducted a study that reviewed disciplinary actions. Common violations included failure to obtain continuing education, the standard of care, and boundary violations. Over 50% of the violations were committed by licensees with ten or more years of experience.

Boland-Prom et al. (2015) collected data on sanctioned social workers and reported that social workers in their twenties were more likely than other age categories to have sanctions for recordkeeping. Continuing education and lapsed licenses were problems for social workers in their thirties and sixties, while those in their fifties had more standard-of-care violations. Sanctions such as license revocation and license surrender were the leading type of discipline. Boards also sanctioned licensees using suspensions, reprimands, and warnings. Boland-Prom (2009) called for more research regarding social worker violations and sanctioning to improve social work supervision, education, and management.

Gricus and Wysierkierski (2021) is perhaps the most influential study, comparable to the one underlying this article. Gricus and Wysierkierski conducted an extensive study in which social workers read vignettes created from actual violations of jurisdiction regulations and rated the seriousness of the violations and the importance of disciplining the social worker. They reported a strong relationship between the perceived seriousness of the incident in the vignette and the importance of discipline. In other words, as seriousness increased, so did the importance of discipline. Additionally, Gricus and Wysierkierski (2021) explained that additional considerations, such as length of time, affected the perception of the seriousness and importance of discipline, while personal characteristics, such as race, did not. They posed several research questions to consider the contextual picture of violations of professional practice. They focused on social workers’ perception of violations, why the Code encourages rank ordering of principles, and whether it is used in regulatory board decision-making. Boland-Prom and Alvarez (2014) recommended increasing the transparency of reported sanctions, including detail regarding the unprofessional conduct and category of the misconduct.

Board Regulation Process

Krom (2019) identified common steps in disciplinary processes among licensing boards. First, a professional violation (wrongful act) must be identified and reported to the jurisdictional licensing board. Most boards have information online about how to file a complaint. Individuals may be reluctant to report unprofessional conduct due to fear of reprisal or belief that the issue was not important enough to report, or they may not know where to register a complaint. Finally, the jurisdictional board must adjudicate the complaint and impose sanction when warranted. Krom (2019) also found variation among the jurisdictions in how they investigate violations and how board members assess investigation results to inform decisions.

Board Member Training

Regulatory boards follow the laws that establish regulations and practice standards; boards also sanction individuals for practice violations as a necessary point in protecting the public. Board members must also be trained to understand their roles as regulators beyond their professional identifications (ASWB, 2018). The need for adequate preparation to become a social work board member has been established; yet previous research has not explored the factors that affect board member decision-making about allegations of unprofessional social work practice.

Rationale for the Study

The US is a world leader in social work regulation and other countries look to the US as a model. Decisions made by regulatory boards have significant impact on protection of the public as well as standards of practice for social workers. It is vital that jurisdictional boards have some measure of consistency in their decision-making processes as well as equity in sanctions. This study aims to develop a body of knowledge that informs board member decision-making regarding the sanctioning of social workers. The knowledge gained from the study can inform board members who review allegations of how other board members might implement violations and sanctions across jurisdictions, thus promoting consistent, equitable, and proportionate sanctions.

Methods

The University of Wisconsin – River Falls Institutional Review Board approved this exploratory mixed methods study. The researchers included six social work educators participating in the ASWB’s Pathway to Licensure Institute (ASWB, 2019), two of whom have served on boards regulating social workers and one executive director of a jurisdictional licensure board.

Participants

The researchers conducted an online survey of social work licensing board members across the US, current or having served within the past five years, in order to assess the factors influencing social work board members’ decision-making. A total of 21 board members from 12 jurisdictions participated in the study, though not all respondents answered every question. The participation represents approximately 5% of eligible social work regulators (ASWB personal communication, 2022).

Procedures

To ensure confidentiality, the survey was conducted via Qualtrics, and no identifying data were collected nor provided to the researchers. No incentives were provided to participants. The survey link was posted in a newsletter sent electronically by ASWB to social work licensing board members in all US jurisdictions. The study opened with an explanation of the study and purpose, and participants were asked to verify eligibility. Eligible participants completed demographic questions regarding age (grouped by decade), gender, ethnicity, profession, and years of professional experience. In addition, participants were asked to identify their board type (social work only vs composite) and their board jurisdiction. The survey also asked for years of experience on the board. Participants advanced to the next phase of the study where they were asked to rank order the seriousness of twelve listed violations. The last phase of the study involved review of four vignettes in which social workers were engaged in unprofessional conduct. In each, participants were asked to use a Likert scale to rate the seriousness of the alleged behavior, the importance for the board to sanction, and select the most fitting sanction from a list of options. Participants were also asked if their opinion of the seriousness of the behavior would change using six variables: BSW vs. MSW, less than vs. more than two years of experience, admission vs. denial of the allegation, the client reported no harm vs. harm, the social worker was male vs. female, and race of the social worker was known vs. unknown.

Study Design

Before reading the vignettes, participants were asked to rank the seriousness of licensing violations most reported to jurisdiction licensure boards, as reported in prior studies (Boland-Prom, 2009; Boland-Prom et al., 2015; Daley & Doughty, 2007; Gricus & Wysiekierski, 2021).

The use of vignettes in this study was modeled after Gricus and Wysiekierski (2021). The four vignettes were based on general social worker violations: breaking professional boundaries (non-sexual), fraudulent reporting, improper termination, and impairment. The vignettes were created after reviewing common complaints submitted to one jurisdiction licensing board. Similarly, the questions about the seriousness of violations and the importance of the board to sanction were modeled after the Gricus and Wysiekierski (2021) study. Researchers were intentional in this method in order to offer some basis for comparison between social worker perception and board member perception of these variables.

Upon completing the phase of the study involving vignettes, participants were given opportunity to provide comments. This was an exploratory study; no results were hypothesized.

Results and Discussion

Demographics

Of the 44 individuals who responded to the survey, 27 (61%) reported being eligible to complete the study, 11 did not answer, and six noted ineligibility. Of the 25 participants providing demographic information, the majority were white women between the ages of 51 and 70. Further explanation of demographics include age: one was 31-40 years, seven were 41-50 years, eight were 51-60 years, eight were 61-70 years, and one was 70+ years of age; gender: 12 were female, 11 were male, and two preferred not to identify; and ethnicity: 18 were White, one was Black, two were Asian, two were Native American, and two preferred not to answer.

Twelve jurisdictions were represented, covering all regions of the US; however, 7 of the 19 (37%) respondents indicated living in the Midwest jurisdictions of Ohio, Indiana, and Minnesota. Other jurisdictions represented included Arkansas, California, Georgia, Idaho, Michigan, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and West Virginia.

The professional composition of the sample included 17 social workers, two mental health counselors, two public representatives, one addictions counselor, one academic, and one guardian ad litem. Years of experience in their profession ranged from seven to 49 years, with a median of 26.46 years. Of the 24 that indicated years of professional experience, 11 indicated having between 20 and 29 years of experience, while five had over 40 years of experience, four reported between 30 and 39 years of experience, and four reported 19 years or less of experience.

Participants were asked to describe their board member experience. Of the 21 responses, 12 indicated serving on a social work-only board, while nine served on a composite board. This is a slight overrepresentation of composite board members, as composite boards make up only about 30% of all licensing boards across the US (ASWB, personal communication, 2022). Of the participants, 14 of 20 reported serving on the board for less than ten years.

Open-ended, qualitative data was collected from 19 participants about their experiences with board member orientation. Orientation experience included attending formal new board member training provided by ASWB, face-to-face training by the jurisdiction Executive Director and staff, and self-directed orientation via manuals, emailed documents, and previous board agendas and minutes. Nearly two-thirds of respondents (12 of 19) identified the ASWB training as a critical part of their orientation.

Participants were asked an open-ended question about how their board conducts investigations. There was some variety in the details of responses. However, most followed a general process of complaint received, assigned to an investigator, the subject of the complaint was allowed to respond, the board chair or other member reviewed information, then the entire board formally voted on outcomes. About half of the participants reported that their boards have staff complete the investigations. In contrast, just over a third used investigators from their jurisdiction’s Attorney General’s (AG) office, and the others reported a combination of staff and AG office investigators. Some participants mentioned using settlement conferences or consent agreement processes before being sent to the entire board for review. In some situations, a committee of board members or the board chair was primarily responsible for final outcomes. However, the majority involved the entire board in the final sanctioning decision.

Ranking of violations

Participants were asked to rank order a list of licensing violations from 1 (most important) to 12 (least important). Table 1 provides details of these results. The most apparent consensus among the participants regarded the breaking of professional boundaries, with sexual, as the most severe violation. From there, breaking client confidentiality, breaking professional boundaries, non-sexual, and billing fraud was considered less severe but similarly important. Impairment, inadequate standard of care, practicing without a license or with an expired license, and felony conviction after receiving a license were in the third most important group of violations. Inadequate record keeping, improper termination, and committing a misdemeanor during practice were among the fourth most important violations. Most participants saw not meeting continuing education requirements as the least important violation. The greatest variation in determining importance was found for practicing without a license or with an expired license, billing fraud, improper termination, and inadequate care.

| Range of rank | Most frequent rank | Mean | Median | Rank Median | Rank Mean | |

| Breaking professional boundaries, sexual | 1st-5th | 1st | 1.6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Breaking client confidentiality | 2nd-9th | 2nd, 3rd | 4.3 | 3.5 | 2 | 2 |

| Breaking professional boundaries, non-sexual | 2nd-9th | 4th | 4.35 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Billing fraud | 1st-9th | 3rd, 7th | 4.45 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Impairment | 1st-11th | 5th | 5.25 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Inadequate standard of care | 6th-12th | 10th | 5.85 | 5.5 | 6 | 6 |

| Practicing without a license or with an expired license | 1st-12th | 4th, 7th | 6.5 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Felony conviction after receiving license | 2nd-10th | 8th | 6.65 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Inadequate or lack of required record keeping | 6th-12th | 10th | 8.95 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Improper termination | 5th-12th | 7th, 9th | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| Misdemeanor in the course of practice | 6th-12th | 11th | 9.75 | 10.5 | 11 | 11 |

| Not meeting continuing education requirements | 8th-12th | 12th | 11.35 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

Vignettes

For each vignette, respondents were asked to determine the seriousness of the incident, the importance of disciplinary action, and recommendations for disciplinary action. They were also asked whether the level of education (bachelor or master), more vs. less than two years of experience, social worker admission vs. denial of the violation, client reports harm vs. no harm, the social worker was male vs. female, or if race of the social worker were known vs. unknown would change the seriousness of the incident.

Vignette 1

A complaint that a social worker blurred professional boundaries was submitted by a client’s mother. The client is a 21-year-old White female who sought help for anxiety one year earlier. The social worker diagnosed anxiety and depression. As treatment progressed, the social worker offered the client her cell phone number and personal email. The client indicated she called the social worker frequently just to talk “like I would with my mom”. These calls and texts were not always documented in the social worker’s progress notes. The client asked to follow the social worker on social media. The social worker occasionally “liked” posts from the clients. The social worker attended the client’s birthday party at a local pub where the client’s friends, family, and co-workers were present. The social worker indicated she was invited.

Overall, 17 of the 19 participants ranked the violation a 5 or higher on a 7-point scale from 1 (not at all serious) to 7 (very serious), and 17 of the 19 participants ranked 5 or higher that it was important to discipline the social worker. See Table 2.

Of the 21 participants who identified sanctions, 15 indicated a reprimand was the appropriate sanction, four selected non-public caution, and two selected suspension. Of the 15 who recommended a reprimand, 13 recommended additional training, and 12 indicated that supervision should be required.

In considering the factors that might change the seriousness of the incident, most agreed that the various factors would not change the seriousness of the violation. Of the 20 who responded, nine stated the seriousness of the violation was increased if the social worker had a master’s degree, and four indicated an increase if the social worker was male. Five responded that the seriousness was decreased if the social worker had less than two years’ experience, and three responded with a decrease in seriousness if the social worker admitted behavior. See Table 3.

Vignette 2

Following an investigation based on a 67-year-old, African American female client asking about her appointment, an agency supervisor submitted a complaint that a licensed social worker falsified visitation records of five clients. The public agency serves the physical, mental, and social needs of clients 65 and older in a seven-county region. Each social worker has a caseload of approximately 90 clients, with whom they need to visit in the home at least once every three months. The supervisor submitted the allegations, providing evidence that on five different occasions the social worker documented that she visited the client, but each of the clients told the supervisor there was not a visit on those dates. The social worker stated she was unable to keep up with the minimum agency deliverables.

For this vignette, 19 participants responded. The vignette was deemed slightly more serious than the first, with 16 responses scoring 5 or higher on the Likert scale. No response was rated lower than 4. The respondents were less likely to deem it important that the licensure board discipline the social worker, although there were no responses of 2 or 1 (not important). Fewer respondents, in this case, 15 of the 19, indicated that discipline was important compared to the first vignette. See Table 2.

In Vignette Two, the sanction recommended was more likely to be a reprimand vs. a non-public caution or a suspension. Of the 18 participants who identified sanctions, 11 indicated a reprimand was the appropriate sanction, two selected non-public caution, three selected suspension, and two selected revocation. Of the 11 who recommended a reprimand, 10 recommended additional training, eight recommended supervision be required, and one recommended a fine.

When examining the qualifying factors, the results were similar to the first vignette. The race of the worker was least likely to change the seriousness. Being a master’s level practitioner was seen as most likely to increase the seriousness though substantially less significant than in Vignette One. Admitting the offense and lack of experience were perceived as lessening the seriousness. The gender of the social worker was viewed as having no effect on the seriousness. See Table 3.

Vignette 3

A director of a chemical dependency prevention agency submitted an allegation that a licensed social worker did not terminate properly with her support group clients. The attendance in the support group ranged from 8-10 persons, ranging in age from mid-20s to mid-50s, and from diverse cultural groups. During the investigation interview, the social worker stated she had many disagreements with her supervisor’s evaluation of her and many complaints about the agency over the last six months. She gave a two week notice and did contact her individual clients, either by phone or in person. None of those clients were in the support group, and the support group did not meet during the social worker’s last two weeks of employment. The social worker felt it was inappropriate to notify the support group members by phone. The support group was co-led by another social worker, so the licensee felt there was no discontinuation of services for the group. The licensee felt the agency director filed the allegation because the agency director was upset that the social worker only gave two weeks’ notice when resigning.

Unlike the first two vignettes, the majority, 15 of the 19 participants, indicated the violation rated lower in seriousness (rating of 3 or lower). Only one respondent rated with score of 4 or higher on the Likert scale. Not surprisingly, the majority, 16 of the 19 respondents, also deemed it of low importance for discipline (rating 3 or lower). See Table 2.

Of the 18 participants who identified sanctions, 16 selected non-public caution, and two selected reprimand. Of the two who recommended a reprimand, both recommended additional training, and one recommended supervision.

The qualifying factors contributed little change to the perception of seriousness by the respondents. The social worker as a master’s level practitioner was perceived to increase the seriousness of the incident; this factor aligns with the previous two vignettes. See Table 3.

Vignette 4

A Clinical Director of an outpatient setting submitted a complaint alleging that a licensed social worker had been cancelling an inappropriate amount of client appointments. The director alleged that many were cancelled last-minute, without appropriate or timely notice to clients, often not showing up to appointments even though clients arrived for the service. The director reported having evidence to prove that the social worker has “no-showed” on at least six occasions over the course of four weeks and has cancelled “more than 15 sessions”, but with only three clients more than once. Also alleged within the complaint is that clients had reported to the clinical director that the social worker had often been negligent during sessions, for example texting or stepping out briefly to take personal phone calls. The director heard this from at least four clients over the last month. Two clients reported that they think the social worker dozed off briefly during a session. The social worker cancelled several appointments due to personal reasons and reported having been under a “large amount of stress.” The social worker reported to the board that her mother recently became terminally ill, and she is now the full-time caregiver of her mother outside of her work hours.

Responses in the first three vignettes were consistent; however, this vignette had notable variability in the responses. While the mean perception of seriousness was 5.1, the responses were split between very and moderately serious. Of the 19 respondents, 13 selected a seriousness rating of 5 or higher on the Likert scale, and six selected ratings of 3 or 4, and no participant selected seriousness less than 3. Ratings of importance to discipline were slightly different with 11 selecting a rating of 5 or higher in importance, three selecting ratings of 3 or 4, and five selecting the importance to discipline as low. See Table 2.

| Vignette (n=19) | Measure | Seriousness | Importance to Discipline |

| Vignette 1 | 7 (very) | 3 | 11 |

| 6 | 6 | 3 | |

| 5 | 8 | 3 | |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 (not at all) | 0 | 0 | |

| Analytics | Mean 5.37 Median 5 Mode 5 | Mean 6.1 Median 7 Mode 7 | |

| Vignette 2 | 7 (very) | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | 8 | 8 | |

| 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 (not at all) | 0 | 0 | |

| Analytics | Mean 5.63 Median 6 Mode 6 | Mean 5.68 Median 6 Mode 6 | |

| Vignette 3 | 7 (very) | 0 | 1 |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | |

| 5 | 0 | 1 | |

| 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| 3 | 5 | 5 | |

| 2 | 7 | 5 | |

| 1 (not at all) | 3 | 6 | |

| Analytics | Mean 2.63 Median 2 Mode 2 | Mean 2.47 Median 2 Mode 2 | |

| Vignette 4 | 7 (very) | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | 7 | 4 | |

| 5 | 4 | 5 | |

| 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| 1 (not at all) | 0 | 1 | |

| Analytics | Mean 5.1 Median 5 Mode 6 | Mean 4.4 Median 5 Mode 5 |

Of the 21 participants who identified sanctions, 14 indicated a reprimand was the appropriate sanction, six selected non-public caution, and one selected suspension. Of the 14 who recommended a reprimand, eight recommended supervision, six recommended additional training, six recommended counseling, and one recommended a fine. The respondent who recommended suspension also recommended supervision and training. No one recommended revocation of license.

The importance to discipline leaned toward more important, although a quarter of the respondents indicated it was not at all or not important. At a higher rate than the other three vignettes, counseling was recommended in addition to reprimand and suspension. Supervision and training were also more utilized in sanctions.

As in the first three vignettes, the qualifying factors were perceived as having little impact on changing the seriousness of the offense. Having a master’s degree was perceived to increase seriousness. The client reporting no harm reduced perceived seriousness. Admission by the social worker produces interesting results in this vignette as some perceived it to increase seriousness while others perceived it to decrease. See Table 3.

Vignette Comparisons

There were significant differences across the vignettes in terms of both perceived seriousness F (3.54) = 22.94, p < .001, and importance for the board to sanction the social worker, F (3.54) = 21.79, p < .001. Vignette 3 was perceived as notably less serious and less important for the board to sanction.

The ranking of vignettes by importance to discipline mean scores (see Table 2) aligns with respondents’ rank ordering seriousness of violations (see Table 1). Vignette 1 was ranked being most important to discipline, followed by Vignettes 2, 4, and then 3. However, the seriousness mean scores, per vignette, did not follow the same pattern (see Table 2). Vignette 2 ranked most serious, followed by Vignettes 1, 3, and then 4. One would expect to see a pattern of the highest perceived seriousness and highest importance to discipline. The difference here is most likely explained by the mean seriousness scores for Vignette 1 (5.37) and Vignette 2 (5.63), indicating very similar levels of seriousness and different perceptions by respondents on the most relevant sanctions for the different behaviors demonstrated in the vignettes.

Most participants reported no change in the seriousness when considering six factors in the vignettes; however, a few differences were found and are worthy of discussion. The perceived seriousness of allegations increased or greatly increased (26%) if the social worker was master’s level educated in all four vignettes. The social worker having less than two years of experience was perceived to decrease the seriousness in Vignettes 1 (non-sexual boundary violation and lack of documentation) and 2 (inadequate standard of care and inadequate recordkeeping), but potentially increase the seriousness in Vignette 4 (impairment and inadequate standard of care). The social worker admitting the behavior was perceived to decrease seriousness in Vignettes 1, 2, and 3; however, the effect of admission in Vignette 4 was less clear. Gender of the social worker was perceived as increasing seriousness in Vignette 1, but no effect in Vignettes 2, 3, or 4. See Table 3.

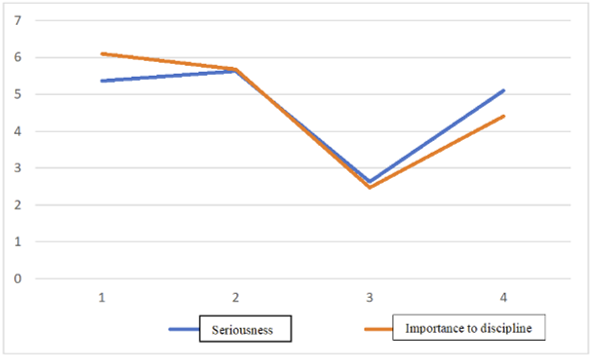

Graph 1 visually demonstrates the significant relationships between mean scores of Seriousness and Importance to discipline among the four vignettes. While there is a slight variation, the mirroring of the pattern of means between seriousness and importance to discipline represents consistency in the performance of the vignettes and the validity of the responses by participants.

There was consistency in the outcomes of each vignette regarding seriousness. Each vignette skewed highly toward either very serious or not at all serious and there was little variability on the opposite ends. The participants collectively deemed Vignette 2 as the most serious. It was surmised that the falsification of records, which required a conscious decision by the social worker to act unethically, contributed to the determination of a high level of seriousness in this situation. This was followed by Vignette 1, which also alleged inadequate documentation but withheld suggestions of intentional behavior. Vignette 4, which described unprofessional conduct on the part of the worker but in the context of personal struggles, was not seen as serious as other violations, but still serious. Researchers assume that context mattered in this vignette; however, the impact on clients was clear, which likely maintained some level of seriousness in the case. Vignette 3 was regarded as improper termination which seemed to suggest that context mattered. Perhaps participants considered the situation to be more of a disagreement between the worker and the supervisor since there was no reported impact on clients.

The recommendations for disciplinary action followed the same tendencies as the perceptions of seriousness. The most variability occurred in Vignette 4, which indicated an overall intent by the participants to address the issue, but not in a punitive manner. When selecting sanctions, training, and supervision were the most frequent addition to the sanction. Fines and counseling were rarely chosen, with the exception of Vignette 4 where the social worker reported personal stress as a contributing factor to the violation.

Graph 1 visually demonstrates the significant relationships between mean scores of Seriousness and Importance to discipline among the four vignettes.

Limitations

As with any exploratory study, there were several limitations. First, the sample size was very small, representing fewer than 5% of the members serving on social work regulatory boards. It was possible that a larger sample may have produced more variability in the responses. In addition, the sample was strongly represented by white, female, and older respondents, which may have impacted the results, especially regarding the question about the race of the social worker. Participants from composite boards were overly represented in this sample, which also may have impacted the results. This is important to consider in future research, given the need to understand how much decision-making is tied to social work values versus those of other behavioral health professionals, those in other helping professions, or the values of board members who are not licensed professionals. Finally, at least half of the respondents were from only three jurisdictions, which may have overrepresented the consistency of board member perceptions.

There were also limitations within the study design. Participants could answer any part of the study which may have contributed to inconsistency among the data. Because results were received in the aggregate, the pattern to which questions were skipped was unclear. The survey completion timeline was less than four weeks and spanned end-of-the-year holidays. This may have affected available time and who was willing to participate in the study. Another factor affecting participation was the time intensity of up to thirty minutes to complete the study with no incentive or remuneration.

Regarding whether the social worker’s race changed the seriousness of the violation, two responses may have been due to misapplication of the scale as they seem inconsistent with other responses. Participants were not given information about the race of the social worker in initial vignettes, so changing the race later in the questions may not have been accurately assessed. Further, consent agreements, disciplinary supervision, and diversionary measures may have influenced the ways different board members viewed the ranked misconduct in the vignettes. Balancing the provision of enough information for the participants to make good decisions and not making the survey take an inordinate amount of time also may have contributed to some participants unintentionally adding their own contexts from experience. Finally, it cannot be overstated that this study collected only a small sample of participants, and while the results are meaningful in many ways, they cannot be generalized about board member decision-making. The results promote substantial thoughts, and raise more questions for further consideration for future research.

Implications

As stated in the literature review, some research has explored social workers’ perceptions of violations already sanctioned by jurisdictional licensing boards or reviewed by NASW. This exploratory study examined the perceptions of board members who make the decisions about social worker violations and the sanctions for those violations. Although the sample size was small, the results of this study are important because, as the quantitative data demonstrated, many non-social workers serve on boards that hear allegations and determine sanctions for social worker violations. The qualitative data reveal that board members may make decisions based on investigations done by other personnel, often persons with legal expertise, who determine if the allegation violates the jurisdictional licensure law. The results of this study may be more influenced by respondents’ familiarity with the legal regulation of social work practice than knowledge of the NASW Code of Ethics as the basis for judging the seriousness of the violations and the importance to discipline.

Though the respondents connected the seriousness of the offense to the importance to discipline, which matched conclusions from prior studies (Boland-Prom, 2009; Gricus & Wysiekierski, 2021), there were some contradictions. For example, Vignette 2 had the highest mean score on the seriousness scale, but Vignette 1 was rated higher on the importance to discipline scale. Respondents may have focused on other variables in the vignettes besides the primary allegation. Additionally, jurisdictional legislation may influence the perception of the seriousness of the violation. Further, Vignette 3 was used in the study because it was a common violation written into the law in some jurisdictions; however, respondents rated this violation low in both seriousness and importance to discipline. In some jurisdictions, improper termination may not be stated explicitly as a violation but rather subsumed under a more general category, such as standards of ethical practice and professional conduct. Future research may include a content analysis of different jurisdictional legislation to assess whether laws highlight some more serious violations than those in other jurisdictions. This study also identified that sanctions, primarily reprimands with training and supervision required, were often recommended for more serious offenses. Other factors identified as important include the educational degree of the social worker, whether the social worker admitted the offense, and the number of years of experience of the social worker, and these influenced the seriousness of the offense for some respondents.

The majority of respondents reported attending the ASWB new board member training, which uses case examples to apply the Model Social Work Practice Act (ASWB, 2018). The vignettes and survey questions used in this study, followed by discussion, could be used as tools for board member training. Further exploratory and descriptive studies of board member training may provide more understanding of the contextual influences of board decision-making.

Since the majority of participants reported attending ASWB new board member training as part of their orientation, it would be helpful to understand if the consistencies observed in this study were due to attending the same training; thus, board members are trained to think similarly about violations and expect similar outcomes. If there is belief that the measures are adequate for seriousness, the importance of the need to discipline, and the sanctions themselves, then the influence of this orientation serves jurisdictional regulatory boards well. If not, then ASWB’s new board member orientation may be a place to influence board member decision-making. Further research is needed to explore how jurisdictional legislation uses the Model Social Work Practice Act (ASWB 2018) in creating board regulatory practices. Additional research regarding how boards and board members determine sanctions imposed would be useful.

References

Adams, T., (2020). Health professional regulation in historical context: Canada, the USA and the UK (19th century to present). Human resources for health, 18(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00501-y

Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB), (2018). Model social work practice act. https://www.aswb.org/regulation/model-social-work-practice-act/

Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB), (2019). Path to licensure institute. https://www.aswb.org/licenses/path-to-licensure/path-to-licensure-institute/

Boland-Prom, K., (2009). Results from a national study of social workers sanctioned by state licensing boards. Social Work, 54(4), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/54.4.351

Boland-Prom, K. & Alvarez, M., (2014). School social workers sanctioned by state departments of education and state licensing boards. Children & Schools, 36(3), 135-144. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdu012

Boland-Prom, K., Johnson J., & Gunaganti, G., (2015). Sanctioning patterns of social work licensing boards, 2000–2009. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(2), 126-136. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2014.947464.

Cooper-Bolinskey, D., (2019). An emerging theory to guide clinical social workers seeking change in regulation of clinical social work. Advances in Social Work, 19(1), 239-255. https://doi.org/10.18060/22622

Council on Social Work Education (2018). Curricular guide for licensing and regulation: 2015 EPAS curricula guide resource series. CSWE Press.

Daley, M. & Doughty, M., (2007). Preparing BSWs for ethical practice: Lessons from licensing data. Journal of Social Work Values & Ethics, 4(2), 3-9.

Goodenough, K., (2021). Exemption from social work licensure: A historical perspective. Doctoral Dissertation: County exemption from social work licensure in Minnesota: Understanding the past and present to affect the future. University of Minnesota School of Social Work: St. Paul, Minnesota.

Gricus, M., & Wysiekierski, L., (2021). Social workers’ perceptions of their peers’ unprofessional behavior. Journal of Social Work, 0(0), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680173211012576

Krom, C. L., (2019). Disciplinary actions by state professional licensing boards: Are they fair? Journal of Business Ethics, 158(2), 567-583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3738-5

Magiste, E.J., (2020). Prevalence rates of substantiated and adjudicated ethics violations. Journal of Social Work, 20(6), 751-774. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017319837521

National Association of Social Workers (NASW), (2021). The NASW Code of Ethics and State Licensing Laws.

Strom-Gottfried, K., (2003). Understanding adjudication: Origins, targets, and outcomes of ethics complaints. Social Work, 48(1), 85-95. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/48.1.85

Stuart, P., (2013). Social work profession: History. Encyclopedia of Social Work. Oxford Research Encyclopedias.