Archives > Volume 20 (2023) > Issue 2 > Item 09

DOI: 10.55521/10-020-209

Katherine Drechsler, DSW, LCSW-SA

University of Wisconsin-Whitewater

drechslk@uww.edu

Candice C. Beasley, DSW, LCSW-BACS

Tulane University

cbeasley@tulane.edu

Melissa Indera Singh, EdD, LCSW

University of Southern California

singhmi@usc.edu

Drechsler, K., Beasley, C. & Singh, M. (2023). Critical Conversations in Compensating Social Work Field Education: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 20(2), 169-199. https://doi.org/10.55521/10-020-209

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of IFSW.

Abstract

This article challenges social work programs to have the critical conversation of paid/compensated practicum education experiences. The social work profession is embedded in identified values and ethics. Reviewing the historical practice of unpaid practicum education placements from a lens of the social work profession’s fundamental values and ethics is essential for the continued success of social work education and its programs. A systematic review was completed to locate literature that either substantiated the need for paid and/or compensated practicum education placements or provide guidance to social work programs on how to engage in critical conversations regarding the implementation of paid / compensated practicum education experiences. There were no results found in the literature that substantiated the need or reflects that social work education, within the USA, are having conversations on compensated practicum experiences. A call-to-action challenges social work programs to have these conversations as to support the success of social work students. Implications of compensated practicum education for social work students, social work programs, practicum sites, and scholars will be discussed.

Keywords: Social work practicum education, paid practicum placements, compensated practicum education

The Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) has deemed field education, also referred to as practicum education, the signature pedagogy of the social work profession (Council on Social Work Education, 2008). As such, it is the responsibility of the institution to provide equitable practicum opportunities to social work students. Since deeming practicum education as the signature pedagogy, the responsibility of practicum education, as it relates to the student, has not been revisited. The practicum education experience is widely recognized as the most significant component of social work education (Bogo, 2010; Cleak & Smith, 2012; Wayne et al., 2010) as this experience allows the social work student the opportunity to integrate what was learned in the classroom to the development of social work practice skills that will be applied in tangible practice situations. However, in this era of diversity, equity, and inclusion, what has the academy conceptualized, as a collective, in ensuring that all aspects of our social work and practicum education programs are equitable for all students so that practice skill development can be at the forefront of student concern? The National Association of Social Work (NASW) Code of Ethics (2021) calls social workers to be mindful of the inequities and injustices within our communities. Assuredly, social work programs must do the same when analyzing the economic inequities that practicum education may cause for our students, communities, practicum instructors, and community agencies.

Practicum education experiences, in social work education, are highly valued as it plays a critical role in preparing emerging social workers for the social work profession. Social work education researchers have produced substantial knowledge, over the decades, concerning what students believe are helpful approaches, as well as concerns, within their practicum education experience. It has been found that practicum education aims to achieve many goals, with one major goal focusing on student practice competency as to obtain their degree, while concurrently performing well in academic course work. Yet another challenge is the phenomenon of consumerism within higher education. Students enrolling in social work education may have a consumer-focused mindset and make their demands known about what outcomes they expect out of their education (Lager & Robbins, 2004). Some students may approach the practicum experience with an “entitlement philosophy,” and their success, as it relates to their practicum placement grade, should be based on effort and not on the demonstration of skills (Tseng, 2011); all of which may or may not align with social work’s educational and professional competencies.

When analyzing the state of social service agencies and its influence on student practicum outcomes, tacit practice knowledge allows the realization that changes in public services have forced traditional practicum sites to offer more services with less resources. Economic downturns make it challenging to provide student opportunities; thus, social work programs may have difficulty locating timely practicum placements – a challenge that may cause students an unfair delay in practicum hour accrual. Further, the decline in state and federal-funded services has eliminated many positions, held by social workers. Social workers who may have potentially held positions as practicum supervisors; thus, causing an increase in practicum supervision outside of the student’s placement agency. In addition, enrollment changes within the academy have placed pressure on the expansion of social work programs. Diminished resources with increasing expectations for faculty to meet the demands of students with varied needs that are affecting their academics and practicum experience, have exhausted the amount of meaningful skill focused faculty-student engagement within practicum education. The State of Practicum Education Survey found that 47.9% of respondents reported that teaching and research faculty members serve varied and concurrent roles: practicum liaisons, assisting in student monitoring, and communicating with both placement agencies and agency practicum supervisors (Council on Social Work Education, 2015a, p. 17), all responsibilities that reduce faculty-student skill focused engagement. In an already overburdened system, practicum education is being perceived as “resource-intensive” by the placement practicum sites (Preston et al., 2014). When combined with limited resources within both agencies and the academy, these are all assuredly contributing to the already established inequities within the strained practicum education process.

There are also competing demands, outside of the classroom, that the social work student must address if they are to succeed in their practicum education experience. Social work students are entering practicum with varied mental health diagnoses, substance use disorders, trauma histories, and other psychosocial histories that may be managed while engaging in the academic component of their social work education; but, when merged with the additional stressors of practicum education, subsequent psychosocial problems may arise (Bogo et al., 2007; Pooler et al., 2012).

Further, with the rising costs of student loans, unfunded loan forgiveness programs for social workers, and the stagnant salaries of social work professionals, the lack of direct and indirect compensation for practicum experiences may not attract potential social work professionals as in past decades. Social work programs may need to consider different aspects of compensation related to the labor set forth by social work students, so that the profession may attract students beyond those that can financially support their education. Cultural factors, while engaging in the practicum education experience, must also be considered. A study completed by Srikanthan (2019) reviewed the experience of “Black, minority, and ethnic” students and their accounts of their practicum education experience. A central finding of the study was that the practices of the institution and the context of the practicum education process created a racially stratified experience comparable to the labor market (Srikanthan, 2019). The social work profession is guided by a shared understanding of culture and its function within society and among individuals. This same ethical standard that focuses upon cultural factors, must be considered and applied when conceptualizing and formulating the student’s practicum education experience.

Significance of Social Work Practicum Education

Like other practice-based professions (e.g., education, nursing, and the medical practicum), social work education has both an academic curriculum and a practical component known as “field education” or “practicum education” and is viewed as social work’s “signature pedagogy” (Council on Social Work Education, 2008; Holden et al., 2010; Shulman, 2005) and the “gold standard” (Mullen et al., 2007). Shulman (2005) stated that education for human service professionals socializes students: “to think, to perform, and to act ethically” (Shulman, 2005, p. 52) and better prepare students to provide services to clients. Within the United States of America, practicum education requirements are put forth for accredited schools of social work by the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) and the Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS). CSWE recognizes the importance of practicum education:

The intent of practicum education is to integrate the theoretical and conceptual contribution of the classroom with the practical world of the practice setting. It is a basic precept of social work education that the two interrelated components of curriculum–classroom and practicum–are of equal importance with the curriculum, and each contributes to the development of the requisite competencies of professional practice. Practicum education is systematically designed, supervised, coordinated, and evaluated based on the criteria by which students demonstrate Social Work Competencies (Council on Social Work Education, 2015b, p.12).

The theory and knowledge learned in the classroom are executed in a micro, mezzo, and/or macro practice setting, which may be the most critical learning experience (Jones & Sherr, 2014). Practicum education provides an opportunity for students to apply evidence-based practices (EBP) and builds their knowledge and skills (Beiger, 2013; Washburn et al., 2021).

In addition to the number of hours that students must complete, multiple stakeholders are critical to the practicum experience. For a social work student, at a minimum, they engage with a practicum instructor and a faculty practicum liaison. However, additional stakeholders, in the practicum experience, may include preceptors, seminar instructors, and practicum coordinators. Social work programs may also include practicum directors and/or practicum coordinators that manage the practicum education program. Practicum instructors direct the daily activities of the social work practicum experience at the agency for the social work student, while practicum liaisons are faculty members and represent the social work department and/or school – performing the roles of advisor, monitor, consultant, teacher, mediator, and advocate. Hence, the social work student must be attentive to these varied roles, adding to the additional use of the student’s time and resources.

Uncompensated Practicum’s Impact on Students and Families

Time is Money

While indulging in equitable considerations regarding compensated practicum internships, we must consider how the current structure affects the communities that we serve. Undoubtedly, social work students were considered “community members” before their interest in the social work profession and continue to be so upon entry into the academy. According to the NASW Code of Ethics, “social workers should engage in social and political action that seeks to ensure that all people have equal access to the resources, employment, services, and opportunities they require to meet their basic human needs and to develop fully” (National Association of Social Workers, 2021, section 6.04a). If we, as social workers, apply this ethical code to communities and community members, do we not have the ethical obligation to extend this to social work students who are also community members? Are we ethically obligated to ensure that the time vested in completing social work curriculums do not undermine our students’ ability to meet their basic human needs?

While accomplishing a remarkable feat, a graduate degree, this gain comes at an astronomical cost for many social work students, their immediate families, and their communities. Within the United States of America, at the undergraduate level (BSW), social work students complete a minimum of four hundred supervised practicum hours and at the master’s level (MSW), social work students complete a minimum of nine hundred supervised hours (Council on Social Work Education, 2015b). The uncompensated practicum education hours, at the MSW level, equate to approximately 12-24 hours/week, the equivalent of part-time employment.

It is of note that the hours of supervised practicum do not consider the time spent in non-practicum education social work courses, the time utilized in engaging with their practicum education team, the time utilized in studying, and the engagement of practicum seminar course assignments. Time has value; therefore, in conceptualizing the value of time into dollars by utilizing the federal minimum wage ($7.25/hr.) within the United States of America; each masters level social work student “invests” an additional $6,525 towards their education. This “investment” is in addition to the cost of tuition; thus, transferring wealth/resources from the student’s micro / mezzo construct to subsequent mezzo / macro entities (i.e., government-based practicums).

First Gen Families & Financial Hardships

When assessing the holistic construct of the student, social work programs must also consider the intersectionality of first-generation college/graduate students among communities of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and among those from disadvantaged socioeconomic communities. Although social work is a “calling” for many, the decision to enter social work programs is the expectation of acquiring an improved socio-economic status post-graduation by entering a “working” profession. At the same time, social work programs market the plethora of employment opportunities that the student will have access to post-graduation; a marketing strategy that is not entirely forthcoming in divulging the salary of a nuanced social worker within the profession. Social work programs are less transparent in divulging the debt (total debt the student will incur post-curriculum completion) to income (the starting salary acquired post-graduation) ratio for nuanced professionals. The reality is that for many nuanced social work professionals, it may take many years before one’s social work income surpasses the incurred educational debt. For others, it is possible that their educational debt will continue to absorb their social work salary, leaving the question that when considering the economic status of the student and their families, “is it more beneficial to have never embarked upon this professional journey?”

Further, social work programs must be attentive to the evolution of the family construct. Gone are the days when families offer full financial support to students entering higher education. Most students entering social work programs are considered “non-traditional,” including students who are head of household and students who are also parents of college students. According to Parker & Patton (2013), the “sandwich” generation carries the burden of caring for both elderly and/or debilitated parents while also raising their own children. This shift in the family causes a financial burden upon the student and their family, which was not as prominent at the inception of practicum education’s construction. This financial burden may lead to increased student stress, exacerbation in mental health diagnoses, and perhaps the catalyst in the student being forced to utilize the same services within the agencies they intern. Johnstone et al. found a relationship between unpaid internships and financial hardship on social work students in human service agencies that created stress and possibly compromised their learning experience (2016).

Spector & Infante (2020) explored best practices for social work practicum pedagogy and suggested that practicum supervisors should initiate discussions about financial hardships to offer resources such as stipends or vouchers through agency budgets or workshops such as financial literacy. In an exploratory study performed by Unrau et al. (2019), an anonymous survey was conducted on students enrolled in BSW or MSW programs and found that approximately one-third of respondents lacked awareness of the degree cost and received less financial aid than expected. Therefore, as it relates to the academy, uncompensated internships may inadvertently cause an increase in student attrition rates.

Compensation Defined

It is probable that historically, administrators within social work programs have avoided discussions regarding practicum compensation as it is a concept that generally equates to an increase in budgetary considerations. To the contrary, compensation for social work practicum students may include many different features, not just financial. Due to it being understood that “students” are not synonymous to “employees,” as to be considered as an operational definition, the U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics defines compensation as:

the entire range of wages and benefits, both current and deferred, that employees receive in return for their work. In the Employment Cost Index (ECI), compensation includes the employer’s cost of wages and salaries, plus the employer’s cost of providing employee benefits (U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics, 2021, para 19).

Although financial compensation should become a consideration for students engaged in their practicum education, social work programs can include indirect compensation for social work students under the auspices of “benefits.” Nonetheless, through the exploration of direct or indirect compensation, considerations should be through an equity-minded perspective as it is imperative that programs begin to formulate policies and procedures that identifies the individual needs of the student, determines if the program has access to the resources in meeting the identified needs, and how the student will be linked to the available resources or linked to subsequent programs that offer the supportive mechanisms needed for the individual student’s success.

Exploring Compensation

Although financially compensated practicum is not a nuanced concept as it is a practice implemented across the United States, the general concept of compensating students for their practicum placement is seemingly controversial. One argument is that practicum placement experiences are part of an educational process and should not incur financial compensation. Under this opinion, because the student is not an agency “employee,” and functions under the title of “student,” the “educational experience” itself is to be deemed as the compensation. In contrast, a more current opinion that is gaining popularity is that social work practicum time investment is being considered as “unpaid labor.” For many social work students, their productivity level, within their practicum experience, is equal to that of, at the very least, a “part-time employee.” Therefore, can social work education begin to change the narrative and view the practicum experience as an educational experience that also prepares students with realistic professional opportunities, including paid compensation? Social work programs must begin having dialogue surrounding themes that include: should social work programs consider the financial compensation of students when the practicum agency is financially reimbursed for the services provided by the practicum student? Is it unethical and/or immoral to compensate students for their practicum placement hours if it is indeed to be viewed solely as an educational experience? If so, how are students that are engaged in practicum experiences at more financially prominent agencies / institutions able to obtain financial compensation for their educational experience? Finally, if a practicum education program has opportunities for paid practicum placements, how are students informed of these opportunities—are there fair, equitable, and transparent policies in place to decide who should be awarded these opportunities? Is this practice ethical? Was the student included in the decision-making process?

Again, the discussion regarding the financial compensation of social work students’ practicum experience although seemingly controversial, warrants critical conversation and exploration. As social work educators, it is not only our responsibility to prepare future social workers to engage in competent practice, but it is also our responsibility in assisting our students with the practice of self-care. As it relates to this topic, self-care includes the awareness of feasible financial compensation, exploring if social work provides a livable wage for their family construct, and linking one to opportunities where the student may subsidize their income post-graduation.

Aim of the Review

This systematic review aims to locate a body of literature that may either substantiate the need for paid and/or compensated practicum placements or provide guidance to social work programs in formulating critical conversations regarding the implementation of paid / compensated practicum education experiences. This review would establish the foundation for social work education in having the critical conversations regarding the implementation of paid / compensated practicums that are not contingent upon federal financial aid, work-study programs and / or agency intern programs. With the high stakes to perform in practicum education and the noted competing demands on the social work student, it leaves one to question: is social work education providing support to the best of their abilities for the success of students during their practicum education experience, and is social work education supporting the best pedagogical approach to practicum education? Although institutions may have differing concepts of “compensation,” the challenges go beyond students being offered antiquated compensation packages deemed suitable by social work departments and /or schools. Institutions must begin to have critical conversations regarding their responsibility in providing tangible compensation to their social work students, ones that include financial compensation for social work practicum placement experiences. It is also of note that within this study, the MSW degree will be focused upon as the MSW is the terminal degree for the Social Work profession within the United States.

Methodology

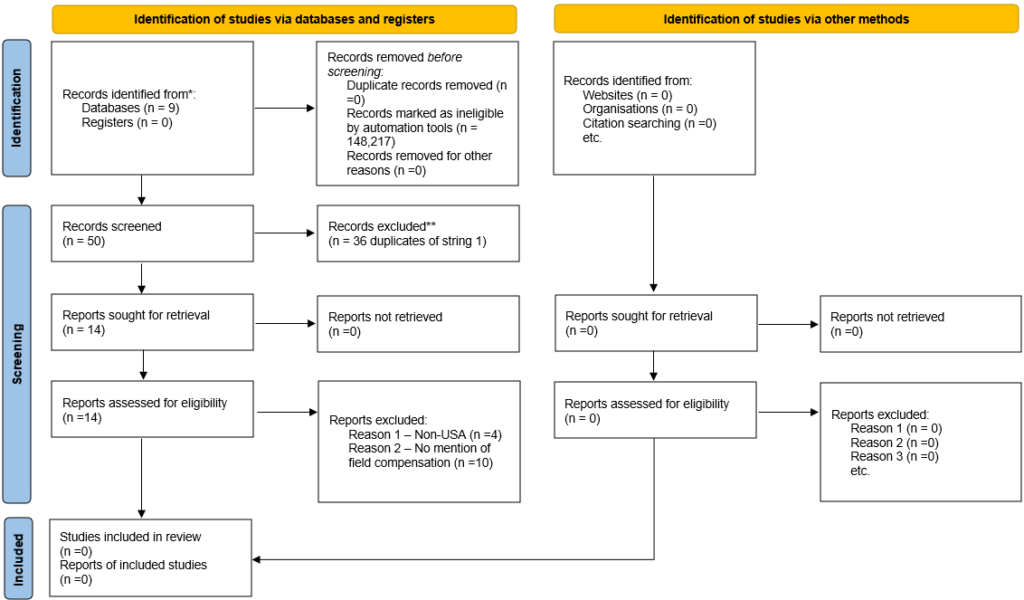

This systematic review was completed using three distinct Boolean threads using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Flow Diagram and PRISMA Statement (Page et al., 2021). The PRISMA Statement and the PRISMA Flow Diagram allowed for the structured flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review. The authors completed a review of the literature that used explicit and systematic methods to collect the findings of the studies. The use of the PRISMA Flow Diagram allowed a consistent research design to review identified articles. The articles and book chapters were reviewed independently by three separate reviewers to identify inclusionary and exclusionary literature. Consensus was reached on the conclusion of inclusionary criteria. The data was organized in a document that included the title of the article, keywords, abstract, inclusionary criteria, and exclusionary criteria. Heterogeneity among Boolean strings were noted and considered.

The first literature review gathered generalized, operational, and current literature regarding paid practicum placements in social work education. To locate this body of literature, a systematic electronic search was performed utilizing the following databases: EBSCO-Academic Search Complete, APA PsycINFO, APA PsychArticles, Educational Administration Abstracts, E-Journals, Professional Development Collection, Psychology & Behavioral Science Collection, Social Work Abstracts, SocINDEX w/Full Text. A 10-year review from June 1, 2011 to June 1, 2021, in the aforementioned databases, screening for: “social work education” or “social work practicum education” or “social work practicum” or “social work internships” and “paid social work practicum placements” and “paid social work internships” was completed. In addition, inclusionary criteria entailed articles and book chapters published between the dates of June 1, 2011 to June 1, 2021; the articles, journals, and books must have been peer-reviewed, published in the United States of America, in the English language, and with full text available. In contrast, exclusionary criteria included articles, book chapters, books and journals that were not peer-reviewed, that were not published prior to the last 10 years, were not published within the United States of America, and were not in the English language. Further, exclusionary criteria were articles and book chapters that did not include Boolean search terms of: “paid practicum placements” and/or “practicums” as well as articles and book chapters that solely focused on BSW programs while failing to incorporate MSW programs.

The second systematic review looked for literature on the generalized concept of “compensated” practicum placements in social work education. To locate this body of literature, a systematic electronic search and 10-year review; from June 1, 2011 to June 1, 2021, was performed utilizing the following databases: EBSCO-Academic Search Complete, APA PsycINFO, APA PsychArticles, Educational Administration Abstracts, E-Journals, Professional Development Collection, Psychology & Behavioral Science Collection, Social Work Abstracts, SocINDEX w/Full Text. The Boolean terms used were: “social work education” or “social work practicum education” or “social work placement” or “social work practicum” or “social work internships” and “compensated internships.” Inclusionary criteria entailed articles and book chapters that were published between the dates of June 1, 2011 to June 1, 2021, were peer-reviewed, published in the United States of America, in the English language, and with full text available. Exclusionary criteria were articles, book chapters, books, and journals that were not peer-reviewed, were not published between the dates of June 1, 2011 to June 1, 2021, were not published within the United States of America, and were not in the English language. Further exclusionary criteria were findings that did not include the Boolean search terms of “compensated practicum placements” and/or “practicums” and articles and book chapters that solely focused on BSW programs while failing to incorporate MSW programs.

The third systematic electronic review searched for literature on uncompensated practicum placements in social work education. In an attempt to locate this body of literature, a systematic electronic search and 10-year review; from June 1, 2011 to June 1, 2021, was performed utilizing the following databases: EBSCO-Academic Search Complete, APA PsycINFO, APA PsychArticles, Educational Administration Abstracts, E-Journals, Professional Development Collection, Psychology & Behavioral Science Collection, Social Work Abstracts, SocINDEX w/Full Text. The Boolean terms used were: “social work education” or “social work practicum education” or “social work practicum placements” or “social work practicum” or “social work internships” and “uncompensated internship or internships.” Inclusionary criteria entailed articles and book chapters that were published between the dates of June 1, 2011 to June 1, 2021, were peer-reviewed, published in the United States of America, in the English language, and with full text available. Exclusionary criteria were articles, book chapters, books, and journals that were not peer-reviewed, were not published between the dates of June 1, 2011 to June 1, 2021, were not published within the United States of America, and were not in the English language. Further exclusionary criteria were findings that did not include the Boolean search terms of “uncompensated practicum placements” and/or “practicums” and articles and book chapters that solely focused on BSW programs while failing to incorporate MSW programs.

Results

In an attempt to capture all aspects of “compensated” practicum internships and / or practicum placements, three separate systematic reviews were conducted using the PRISMA Flow Diagram (Page et al., 2021). The first systematic review includes the search string: “social work education” or “social work practicum education” or “social work practicum” or “social work internships” and “paid social work practicum placements” and “paid social work internships.” The second systematic review includes the search string: “social work education” or “social work practicum education” or “social work placement” or “social work practicum” or “social work internships” and “compensated internships.” Finally, the third systematic review includes the search string: “social work education” or “social work practicum education” or “social work practicum placements” or “social work practicum” or “social work internships” and “uncompensated internship or internships.” Each systematic review was cross-referenced against the remaining two reviews to exclude duplicate studies.

In the first systematic review, the Boolean search string of “social work education” or “social work practicum education” or “social work practicum” or “social work internships” and “paid social work practicum placements” and “paid social work internships,” yielded a total of 148,266 results. Out of this total number, 148,217 were marked as “ineligible” by the EBSCO database automated tool. Of the initial total, 50 articles were screened, with one duplicate. Of the remaining 49 articles, all 49 were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Of the 49 articles, 2 articles were excluded as the articles were not peer-reviewed. Of the 47 remaining articles, 27 articles had research not conducted in the United States of America. Of the 20 remaining articles, 19 articles were excluded as the literature did not mention the Boolean term “paid social work practicum and/or internships,” and 1 article was excluded as it solely focused on BSW practicum education. In conclusion, the first systematic review yielded zero inclusionary studies (Figure 1).

In the second systematic review, which included the Boolean search string of “social work education” or “social work practicum education” or “social work placement” or “social work practicum” or “social work internships” and “compensated internships,” 148,267 results were yielded in total. Out of this total number, 148,217 were marked as “ineligible” by the EBSCO database automated tool. Of the initial total, 50 articles were screened; however, when cross-referenced with the first Boolean string, 36 of the articles were duplicates and therefore, were excluded. Of the remaining 14 records, all 14 were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. After review of the 14 remaining articles, four articles were excluded as the research was not conducted in the United States of America, and 10 articles were excluded as the literature made no mention of the Boolean search term “compensated social work practicum,” “social work practicums,” and/or “social work internships.” In conclusion, this second systematic review yielded zero inclusionary studies (Figure 2).

In the final systematic review, the Boolean search string included the terms “social work education” or “social work practicum education” or “social work practicum placements” or “social work practicum” or “social work internships” and “uncompensated internship or internships,” 148,664 results were yielded in total. Out of this total number, 148,613 were marked as “ineligible” by the EBSCO database automated tool. Of the initial total, 51 records were screened; however, when cross-referenced with the first and second Boolean strings, 27 of the records were duplicates of the first string and one of the records was a duplicate of the second string; therefore, 28 articles were excluded due to these duplications. Of the remaining 23 records, all were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. After reviewing the 23 remaining records, 11 records were excluded as the research was not conducted in the United States of America, 1 record was published outside of the inclusionary time frame; 10 records were excluded as the literature made no mention of the Boolean terms “uncompensated social work practicum,” “social work practicums,” and/or “social work internships.” Finally, 1 record focused solely on BSW programs. In conclusion, this third and final systematic review yielded 0 inclusionary studies (Figure 3).

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to locate literature that (a) substantiated the need for providing differing types of compensation, including those that are financial, to social work practicum students for their time investment in addition to their educational experience; and (b) explored how social work programs engage in critical conversations regarding the implementation of compensated practicum experiences. Out of the myriad of reviewed articles, one article researched in Canada discussed practicum compensation. It is unfortunate that within the period of this systematic review, social work research, within the United States of America, has seemingly not produced accessible peer reviewed literature offering insight on such an important topic.

In a Canadian study, Srikanthan (2019) compares the process of preparing social work students for practicum placement as the equivalent to “securing paid employment” (p. 2175). Srikanthan also refers to the social work practicum experience as the “unpaid and invisible labour of students” and that for BIPOC students specifically, these students are often directed to practicum placements that are historically positions that are “devalued, of low status and underpaid within the labour market” (Srikanthan, 2019, pp. 2174-5). With the pressures of a global pandemic and sociopolitical unrest within the United States, student practicum compensation is needed more than in previous years. COVID-19, especially, has forced many universities outside of their comfort zones, allowing for financial relief that may not have previously occurred in the history of many universities. For example, through the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund (HEERF), the Historically Black Colleges & Universities (HBCUs) of Clark Atlanta University and Spelman College canceled outstanding account balances for students that COVID-19 impacted. CSWE, through policy changes, created accommodations for social work students and practicum agencies impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic; these accommodations were nuanced, were implemented on a national level expediently, and would have never been previously considered, but are now considered “cutting edge,” and are integral parts of social work practicum curricula. The “so what” of this is that if institutions make the active decision to become mindful of student-centered practices, ideas that have never been previously considered can be actualized and implemented. As with the erasure of student debt and the launching of student and agency accommodations on a national level, all of which were conceptualized and implemented during a global pandemic, is it possible that social work programs can collectively conceptualize, actualize, and implement a plan for student compensation for their practicum hours on both a programmatic and a national level?

Future Implications for Social Work Programs

Social work education, and the profession, collectively agree that developing best practices for social work’s signature pedagogy is of utmost importance. Because of this, there has been significant focus on the pedagogical benefits of social work practicum education. Consequently, there has been no significant focus on the differing financial burdens, stressors, and barriers that the practicum education experience potentially imposes upon the social work student. Further questions for programs to consider: are the cultural aspects of a social work student considered when making the practicum placement? Are practicum placements “driven by” the impact of market demand with the personal, cultural, and structural factors influencing the social work student overlooked or not taken into consideration? Is the allocation of resources influencing practicum placement decisions fidelitous to the program’s pedagogical intent? Is the traditional practicum placement process a rigid format built for a particular group of individuals with privilege and power? Does the practicum placement process consider systemic discrimination and racial biases? These critical processing questions are imperative for social work programs to consider as research indicates that students in social work programs have experienced more trauma than their peers that study business and even medicine (Black et al., 1993).

The practicum education experience, if supported by a structured, well-defined experience through the learning agreement, is an investment in the social work student’s education, the mission of the practicum agency, and the social work profession. Social work education must protect the practicum experience and hold this part of the social work educational experience to a high standard. Challenges in the practicum education process can be at the policy, university, and the community organizational level, not just at the individual level with the student. Some of these challenges include finding qualified practicum placements, supervising students during the practicum placement, and providing quality training for practicum instructors. In addition, best-practice teaching strategies to integrate classroom theory into the practicum education experience whilst supporting the ongoing professional development opportunities for social work students may present further challenges.

There has been an accelerated level of discussion in academia, particularly in social work education, about “unpaid” practicum placements. Are social work practicum students “working for free,” “volunteering,” or shall we continue conceptualizing students’ invested efforts as an educational experience? A solution to the financial burdens of practicum placements is to allow practicum placements that will intentionally serve as future places of employment for the practicum student. Although work-based placements may provide challenges, with the practicum student balancing expectations of being a student with the duties of being an employee (Pelech et. al., 2009), exploring and procuring this genre of practicum may alleviate many of the economic hardships incurred by practicum students. Although financial compensation is widely discussed, it is essential to be mindful that the practicum education experience may also be compensated with the development of social work skills, values, knowledge, and academic credit hours (i.e., academic hours earned via skills acquired through personal experiences). We have a responsibility in determining the relationship between unpaid practicum placements, the financial hardships this may cause, and the compromise these stressors may have on the practicum education learning experience.

Social work programs may consider alternatives to direct compensation (i.e., paid internships, stipends, etc.), such as indirect compensation models (i.e., tuition assistance, access to free licensure prep courses, continuing education assistance, etc.). Further, in the spirit of equity-minded practice, a subsequent alternative is offering choice to the student. Some students may view the act of providing their personal time to communities as a form of indirect compensation; thus, choosing “volunteerism” over competing compensation alternatives. The assessment of the student’s compensation preference can be initially explored during the practicum orientation.

Study Limitations

Notable limitations to this study are (a) exclusion of gray literature that may have addressed the topic, (b) exclusion of literature from countries outside of the United States of America, (c) exclusion of literature that was not encompassed within the chosen EBSCO databases; (d) exclusion of literature due to the date of publication, and (e) exclusion of literature that does not have full-text availability.

As to address the common journal bias of only publishing studies with successful outcomes, dissertations are sometimes included in research manuscripts (Campbell Collaboration, 2014). Although considered scholarly work, dissertations were not included in this study as dissertations generally do not comply with the inclusionary criteria of “peer-reviewed.” One article mentioned the compensation of social work students; however, this article was published in Canada. This article was not included in the systematic review, as it is probable that the socio-economic structure of social work and the cultural influences of social work students are different between students in Canada and students in the United States of America. Nonetheless, Covid-19 has caused financial strain to all world citizens on a global level and because of this, subsequent countries may have viable research that may assist the United States’ social work programs with these critical conversations. As it relates to excluded articles, it is probable that the articles which address the context of this research may not have been published in the databases used, may be outside the time parameters, or may not have full-text article accessibility; all of which are definitively limitations of this study.

Conclusion

This systematic review of the literature concluded that there has been no peer reviewed research, that is accessible, regarding either the need or benefits of compensated practicum education in social work programs within the United States. The validation of the importance of practicum education is well noted; therefore, it is critical for social work research to be conducted and accessible as to identify how social work students may be holistically supported throughout their practicum education experience. Conceptualizing research which acknowledges the need for varied types of compensation for student practicum participation, as well as research efforts that include equity-minded compensation opportunities for BIPOC social work students, are all needed to sustain the quality of social work programs and the social work profession.

As indicated by the results, there is a significant gap in the literature on compensating practicum placements, and this has implications for social work education and the future of the social work profession. Social work education aims to prepare competent and ethical social workers with practicum education being a critical component of the social work educational experience. It is clearly stated in the Practicum Education Survey conducted by CSWE in 2018 that “because students become practitioners, the functioning of social systems, the needs of clients and consumers, and the fabric of society are at stake” (Council on Social Work Education, 2018, p. 6). Practicum education looks different today, than in past years, due to a consistently changing world. The results of this systematic review clearly reflect that authentically utilizing compensation as an option in recruiting prospective students to the profession, retaining students, and allowing student success within the practicum education experience is not documented in the literature and shows that perhaps our understanding and verbiage is shifting, as it relates to student needs; however, our practices are not.

In conclusion, now is the time to perform further research and perform comprehensive reviews on the standards and policies guiding practicum education so that we may expediently implement equity-minded supportive solutions as to ensure student success while in practicum. It is not to be viewed as difficult for social work programs to facilitate critical conversations in determining if their individual programs authentically support the individual success of their social work students. Continuing this critical conversation with CSWE, NASW, and subsequent social work programs, on both national and global levels; ultimately allows us to share ideas as one global social work collective, which is essential to the ever-changing dynamics and continued success of social work practicum education.

References

Beiger, R. (2013). Incorporating EBP in practicum education: Where we stand and what we need. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 10(2), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/15433714.2012.663663

Black, P. N., Jeffreys, D., & Hartley, E. K. (1993). Personal history of psychosocial trauma in the early life of social work and business students. Journal of Social Work Education, 29(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.1993.10778812

Bogo, M. (2010). Achieving competence in social work through practicum education. University of Toronto.

Bogo, M., Regehr, C., Power, R., & Regehr, G. (2007). When values collide: Practicum instructors’ experiences of providing feedback and evaluating competence. The Clinical Supervisor, 26, 99-117.

Campbell Collaboration. (2014). Campbell systematic reviews: Policies and guidelines. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 1 doi:10.4073/csrs.2014.1

Cleak, H., & Smith, D. (2012). Student satisfaction with models of practicum placement supervision. Australian Social Work, 65, 243-258.

Council on Social Work Education. (2008). Educational policy and accreditation standards. https://cswe.org/getattachment/Accreditation/Accreditation-Process/2008-EPAS/Reaffirmation/2008educationalpolicyandaccreditationstandards(epas)-08-24-2012(1).pdf.aspx

Council on Social Work Education. (2015a). State of practicum education survey: final report.https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/05519d2d-7384-41fe-98b8-08a21682ed6e/State-of-Practicum-Education-Survey-Final-Report

Council on Social Work Education. (2015b). Educational policy and accreditation standards. https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/Accreditation/Standards-and-Policies/2015-EPAS/2015EPASandGlossary.pdf.aspx

Council on Social Work Education. (2018). Field education survey. Final report. https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/05519d2d‑7384‑41fe‑98b8‑08a21682ed6e/State‑of‑Field‑Education‑Survey‑Final‑Report.aspx

Holden, G., Barker, K., Rosenberg, G., Kuppens, S., & Ferrell, L. (2010). The signature pedagogy of social work? An investigation of the evidence. Research on Social Work Practice. doi:10.1177/1049731510392061

Johnstone, E., Brough, M., Crane, P., Marston, G., & Correa-Velez, I. (2016). Field placement and the impact of financial stress on social work and human service students. Australian Social Work, 69(4), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1181769

Jones, J. M., & Sherr, M. E. (2014). The role of relationships in connecting social work research and evidence-based practice. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 11(1-2), 139-147.

Lager, P. B., & Robbins, V. C. (2004). Field education: Exploring the future, expanding the vision. Journal of Social Work Education, 40(1), 3–4.

Mullen, E. J., Bellamy, J. L., Bledsoe, S. E., & Francois, J. J. (2007). Teaching evidence-based practice. Research on Social Work Practice, 17, 574–582.

National Association of Social Workers. (2021). Code of ethics. https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffman, T. C., Muldrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Stewart, L. A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A. C., Welch, V. A., Whiting, P., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

Parker, K., & Patton, E. (2013). The sandwich generation: Rising financial burdens for middle-aged Americans. PEW Research Center. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/01/30/the-sandwich-generation/

Pelech, W. J., Barlow, C., Badry, D. E., & Elliot, G. (2009). Challenging traditions: The practicum education experiences of students in the workplace practica. Social Work Education, 28, 737-749. doi:10.1080/02615470802492031

Preston, S., George, P., & Silver, S. (2014). Practicum education in social work: The need for Reimagining. Critical Social Work, 15(1), 57–72.

Pooler, D., Doolittle, A., Faul, A., Barbee, A., & Fuller, M. (2102). An exploration of MSW Practicum education and impairment prevention: what do we need to know? Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 22, 916-927.

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027998

Spector, A. Y., & Infante, K. (2020). Community college practicum placement internships: supervisors’ perspectives and recommendations. Social Work Education, 39(4), 462–480.

Srikanthan, S. (2019). Keeping the boss happy: Black and minority ethnic students’ accounts of the practicum education crisis. British Journal of Social Work, 49, 2168–2186.

Tseng, M.T. (2011). Ethos of the day- Challenges and opportunities in twenty-first century social work education. Social Work Education, 30(4), 367-380.

Unrau, Y. A., Sherwood, D. A., & Postema, C. L. (2020). Financial and educational hardships experienced by BSW and MSW students during their programs of study. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(3), 456-473.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021). Glossary. https://www.bls.gov/bls/glossary.htm#top

Washburn, M., Parrish, D. E., Oxhandler, H. K., Garrison, B., & Ma, A. (2021). Licensed master of social workers’ engagement in the process of evidence-based practice: Barriers and facilitators. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 1-17.

Wayne, J., Bogo, M. S., & Raskin, M. (2010). Practicum education as the signature pedagogy of social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(3), 327-339. doi:10.5175/JSWE.2010.200900043

Appendix A: Prisma Flow Chart 1

*Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers).

**If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Database: EBSCO-Academic Search Complete, APA PsychInfo, APA PsychArticles, Educational Administration Abstracts, E-Journals, Professional Development Collection, Psychology & Behavioral Science Collection, Social Work Abstracts, SocINDEX w/Full Text.

Dates: June 1, 2011 to June 1, 2021

Appendix B: Prisma Flow Chart 2

*Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers).

**If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Database: EBSCO-Academic Search Complete, APA PsychInfo, APA PsychArticles, Educational Administration Abstracts, E-Journals, Professional Development Collection, Psychology & Behavioral Science Collection, Social Work Abstracts, SocINDEX w/Full Text. Dates: June 1, 2011 to June 1, 2021

Appendix C: Prisma Flow Chart 3

*Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers).

**If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. http://www.prisma-statement.org/ Database: EBSCO-Academic Search Complete, APA PsychInfo, APA PsychArticles, Educational Administration Abstracts, E-Journals, Professional Development Collection, Psychology & Behavioral Science Collection, Social Work Abstracts, SocINDEX w/Full Text.

Dates: June 1, 2011 to June 1, 2021

Appendix D: Prisma 2020 Checklist

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist item | Location where item is reported |

| TITLE Critical Conversations in Compensating Social Work Field Education: A Systematic Review | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Title Page |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. (purpose, method, results, discussion, and conclusion) | Page 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | Pages 2-11 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | Page 11 |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | Pages 12-14 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | Page 12 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | Page 12 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Pages 11-14 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 12 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g. for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | Pages 15-17 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g. participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | Pages 9-11 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 12 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g. risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | Pages 15-17 |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g. tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | Pages 11-14 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | Pages 11-14 | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | Figure 1,2,3 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | Pages 11-14 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g. subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | Pages 11-14 | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | Page 12 | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | Page 21 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | Pages 11-12 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | Pages 15-17 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | Pages 15-17 | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | Pages 15-17 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | Pages 15-17 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | Pages 15-17 |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | Pages 15-17 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | Pages 15-17 | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | Pages 15-17 | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | Pages 15-17 | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | Pages 15-17 |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | Pages 15-17 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | Pages 17-21 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | Page 21 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | Page 21 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | Page 21 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | None |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | None | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | None | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | Page 23 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | Page 23 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | Page 14 |

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/