Archives > Volume 18 (2021) > Issue 2 > Item 07

DOI: 10.55521/10-018-207

Allan Barsky, JD, MSW, PhD*

Florida Atlantic University

abarsky@fau.edu

*Full disclosure: Allan Barsky, is a member of the JSWVE editorial board. JSWVE uses an anonymous review process in which authors do not review their own work, reviewers do not know authors’ identities, and authors never learn the identity of the reviewer.

Brian Carnahan, MBA

Counselor, Social Worker, and Marriage and Family Therapist Board, Ohio

brian.carnahan@cswb.ohio.gov

Christine Spadola, PhD, LMHC

Florida Atlantic University

cspadola@fau.edu

Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics • Volume 18(2), Copyright 2021 by IFSW

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of IFSW.

Abstract

This qualitative study explored the lived experiences of 13 licensed independent social workers who participated in licensing investigations and received sanctions by a state licensing board for violations of laws, rules, or ethical standards. The researchers used an interpretive approach to analyze the interviews and identify common themes in their experiences. Participants identified 5 key aspects of the investigation process: due process, respect, investigator neutrality, investigator qualifications, and contextual factors. They also described their views on the value of having effective legal representation. This article concludes with recommendations for improving licensing board investigation processes.

Keywords: licensing, complaints, investigations, social work

Introduction

The purposes of professional licensing are to promote safe professional practice and to protect the public from harm (Association of Social Work Boards, n.d.). Licensing supports competent and ethical practice by limiting practice to those who have met particular educational requirements, including basic and continuing professional education (Carnahan, 2019) Licensing laws provide professional guidance about appropriate and inappropriate practice behaviors. Licensure also offers a method of professional accountability and recourse for clients with concerns about their helping professionals. When clients have concerns about professional misconduct, they may submit complaints to their state licensing board. The board conducts an investigation and determines whether the professional has violated any mandatory laws, rules, or ethics governing the professional (Carnahan, 2019). If the board finds that a violation has been committed, the board then determines appropriate sanctions or corrective actions. Sanctions for violations may include reprimand letters, suspension or revocation of licensure, supervision for specific probation periods, or limitations on types of practice (Boland-Prom, 2009). Licensees may also be required to have impairment-appropriate therapy as part of a consent agreement.

Licensing investigation processes are conducted in a confidential manner. Although there have been some published studies on the nature of the complaints against social workers and the types of sanctions provided (Boland-Prom et al., 2015), there is very little published research on what happens within the investigation process (Boland-Prom et al., 2018). The purpose of the present research is to provide greater insight into the investigation process from the perspectives of Licensed Independent Social Workers (LISWs).

The present research was conducted in Ohio. Under the licensing laws in other states, other titles are used (e.g., Licensed Clinical Social Worker or Licensed Master Social Worker). In Ohio, LISWs require a master’s degree in social work from a program accredited by Council on Social Work Education, at least 2 years of post-MSW experience, and at least 150 hours of documented supervision by a licensed supervisor with an LISW-S designation. When the Ohio Counselor, Social Worker, and Family and Marriage Therapist Board receives complaints against social workers, the Deputy Director assesses them for jurisdiction and severity. If the complaint warrants further exploration, a board-approved investigator is appointed to gather information related to the complaint. This may include interviews, research, subpoenaing documents, and legal consultation. The investigators have training in how to conduct investigations. They are not required to have social work degrees or licensure; however, the investigators may consult with social work members of the board. The Social Worker Professional Standards Committee reviews all investigations involving social workers. Four members of this committee must have social work licensure, usually the LISW. The committee also includes a public member who has no social work background. This committee determines whether discipline is warranted based on the investigator’s report. Upon completion of the investigation, allegations may be substantiated or dismissed (Ohio Counselor, Social Worker, and Family and Marriage Therapist Board, n.d.).

The following literature review explores prior research on social work licensing complaints, including the types of complaints that licensing boards receive and the types of sanctions that they impose. Given the relative paucity of research specific to social work licensure, the literature review also explores licensing complaints in other mental health professions. After the literature review, this article describes the qualitative research methods used to explore the experiences and perceptions of LISWs who the subject of licensure complaints. The balance of the article provides the findings of the research and implications of these findings for licensing boards and LISWs.

Literature Review

Until 2003, most research on professional misconduct of social workers was related to professional review processes conducted by the National Association of Social Workers (NASW). Social work licensing did not start until the 1980s, so prior to this time, people with complaints about social worker misconduct had to pursue their issues in court or file a request for professional review with the NASW. Whereas the NASW has jurisdiction to review concerns related to any of the standards in its Code of Ethics, licensing boards may only review cases involving complaints alleging specific violations of the state’s licensing laws.

In a comprehensive study of professional review cases based on ethics complaints against NASW members from 1986 to 1997, Strom-Gottfried (2000a) found that the most common violations involved issues related to sexual and nonsexual boundaries (32%), substandard practice (20%), record keeping (9%), competence (5%), confidentiality (5%), informed consent (5%), infractions with colleagues (4%), reimbursement (3%), and conflict of interest (3%). In a second article, Strom-Gottfried (2000b) studied the literature regarding ethics issues involving social work students, faculty, and field instructors. She found the main areas of ethical concern related to boundaries and dual roles, confidentiality, student evaluation, professional competence, and vicarious liability. She also identified concerns about the fairness of process in handling concerns with students, including problems with notifying students about concerns, fact-finding processes, attempts at resolution, and hearings within the educational institution. In a third article, Strom-Gottfried (2003) describes NASW’s professional review process, including its focus on corrective rather than punitive actions. Unlike licensing boards, NASW cannot prohibit social workers from practicing. Most of NASW’s professional review processes are referred to mediation; hearings are typically used for more serious ethical violations and situations where mediation is not successful. NASW’s review processes are most frequently initiated by clients, family members, employees, and supervisees. Consequences resulting from NASW’s process include censure, supervision, education, suspended membership, restricted practice, personal therapy, refund fees to the client, employer notification, and notification of the state licensing body. Due to concerns about confidentiality of the professional review process, there are no recently published studies about ethics complaints processed by NASW.

Most published research regarding social work licensing violations focuses on the numbers and types of misconduct. Daley and Doughty (2007) examined licensing complaints against social workers in Texas between 1995 and 2003. They noted that prior studies focused on social workers with MSWs. BSWs were underrepresented due to prior restrictions on BSWs joining NASW. The authors found that the most common violations included issues related to boundaries, substandard practice, record keeping, honesty, confidentiality, informed consent, reimbursement, and conflicts of interest. The annual rate of licensing allegations against BSWs was 0.4%, which was similar to the rate of complaints against MSWs. BSWs were more frequently the subject of complaints regarding poor practice and record keeping, whereas complaints against MSWs more frequently related to honesty and confidentiality.

In a study comprising 874 sanctions of LISWs from 27 states between 1999-2004, Boland-Prom (2009) found that the most common violations related to dual relationships (sexual and non-sexual), license-related problems (continuing education non-compliance and lapsed licenses), criminal behavior, and practice falling below expected standards of care. Boland-Prom (2009) highlights the importance of understanding the nature of LISW violations to inform social work supervision, management, and education. Chase (2015) notes that requiring more continuing education does not necessarily solve the problem of ethical lapses as there is no firm evidence that additional continuing education reduces violations. Rather, to prevent violations, it is important to understand the constraints, challenges, peer influences, and pressures experienced by LISWs that can lead to violations.

In a study of 2,607 LISWs sanctioned between 2000-2009, Boland-Prom et al. (2015) found the most common violations were related to recordkeeping and confidentiality. The most frequent sanctions for serious offenses were revocation or voluntary surrender of licensure. Social workers in their 20s were more likely to receive sanctions for problems in basic practice functions such as record-keeping, informed consent, and confidentiality. Workers in their 30s and 60s were more likely to be cited for problems in continuing education and lapsed licenses. Workers in their 40s were more likely to be cited for dual relationships. Workers in their 50s were more likely to be cited for standard of care violations. Boland-Prom et al. (2015) note the lack of detailed information regarding LISW misconduct (e.g., practice contexts, factors associated with violations). They encourage licensure boards to make more information available to researchers so educators, supervisors, and practitioners can have a better sense of how to reduce violations and enhance ethical practice.

In a qualitative study of 18 LISWs (in a Midwest state) who experienced investigation processes, Gricus (2018) found one of the main concerns was a sense that the board presumed LISWs were guilty before completing the investigation. Although some workers felt the board treated them with respect, others suggested that they felt shamed, belittled, or intimidated throughout the investigation process. They did not feel the investigators were caring or empathic. LISWs also expressed concerns that investigators gave no “credit” for their long-term service or contributions to the wellbeing of others. This is the only published study exploring the experiences of social workers in investigation processes. The concerns reported in this study, however, are similar to those expressed by other mental health professions, as described below.

In a survey study of 240 psychologists who experienced licensing complaints (in a southern state), Schoenfeld et al. (2001) found licensees expressed concerns about the board’s process, including a sense that board members responded by “gut reaction” rather than following specific guidelines and that investigators assumed guilt. Some licensees felt the board’s approach was unfair, discourteous, and punitive. Some licensees expressed concerns about conflicts between ethical codes and laws. Others expressed concerns about the processes taking too long, adding to their stress. Even exonerated licensees felt they were subjected to painful and unfair processes. Schoenfeld et al. (2001) suggest that boards implement monitoring processes to ensure investigations are fair and appropriate, and to consider the impacts of investigations on licensees. Peterson (2001) submits that licensees who have violated licensing laws are not necessarily malevolent but may have made judgment errors that should lead to remedial responses rather than punishment. Peterson suggests licensing boards should be proactive, compassionate, understanding, and supportive.

In another survey study, Van Horne (2004) found that despite perceptions that licensing boards are overzealous in sanctioning licensees, less than 0.4% of psychologists will face any licensing board actions and less than 0.13% will face any discipline. In more recent research, Wilkinson et al. (2019) found that just 0.67% of psychologists face any discipline. Still, Van Horne (2004) suggests that licensees have legitimate concerns about licensing board processes, as boards can serve as investigators, prosecutors, judges, juries, and appeals courts. In criminal and civil court cases, due process rights would require independent people to serve in each of these roles. Further, the standard of proof required by boards is either the “preponderance of evidence” or “clear and convincing evidence” rather than “beyond a reasonable doubt,” as required in criminal cases. Given that licensees may lose their ability to practice and earn a living, it is arguable that the preponderance of evidence is too low a bar for proving violations. Further, the financial, emotional, personal, and professional costs can be high even when the psychologist is investigated. Some psychologists who have endured inappropriate investigations and adjudications have been quite vocal and/or litigious in their efforts to publicize their mistreatment by licensing boards (Van Horne, 2004). Licensees have expressed concerns that violations are posted on a publicly disciplinary data website, creating a permanent record that affects them personally and professionally.

Williams (2001) suggests boards should ensure licensees are aware of their rights, including their right to an attorney and their right to know that investigators may use the licensee’s self-incriminating statements or admissions in further actions against the licensee. In some cases, an investigator may find the initial complaint is not validated, but still find other violations in the records or other information shared by the licensee. Sometimes, investigators invite licensees to provide admissions in order to facilitate quick resolution of cases. Investigators should ensure licensees have access to legal advice before they provide such admissions.

In a literature review on the experiences of psychologists facing licensing complaints, Thomas (2005) found that psychologists report feeling terror, outrage, shock, disbelief, guilt, anger, and embarrassment upon being notified of complaints. The stress associated with facing such allegations can compromise psychologists’ objectivity and effectiveness in their clinical work, as well as their responses during the investigation. To cope with the stresses of investigation processes, Thomas (2005) suggests that licensees should consider legal representation, supervision, clinical consultation, therapy, and other sources of support, as needed.

The time between notification and resolution of complaints may be very stressful. Some complaints are reviewed and dismissed quickly when the allegations are unfounded. Others may be dismissed shortly following receipt of an explanatory letter from the licensee. In some cases, complaint processes may continue for months or years (Thomas, 2005). The longer the complaint continues, the greater the costs to the licensee in terms of legal fees, time away from work, and emotional costs. Licensees may also incur costs for clinical consultation and personal therapy. Some licensees, wanting to avoid the costs and stress of a prolonged process, may prematurely agree to a resolution plan, admitting to violations they did not actually commit.

Research Methods

This research used qualitative methods and an interpretive approach (Grinnell et al., 2018) to explore the lived experiences of 13 LISWs in Ohio who had been sanctioned by their state licensing board for violating laws, rules, or ethics. Potential research participants were identified through the website of the Ohio Counselor, Social Worker, and Family and Marriage Therapist Board (n.d.), which lists LISWs who received sanctions. From 2014 to 2019, the average number of complaints received by the Ohio Board was 400 cases per year. Of these cases, an average of 33 cases resulted in a finding of no jurisdiction (e.g., complaints against people who were not licensed social workers), 155 were unfounded (insufficient proof of a violation), 123 resulted in a private caution letter but no sanctions, and 45 cases resulted in sanctions. This research drew a sample from the LISWs who received sanctions.

The first author attempted to contact a random sample of 82 LISWs (by email and/or phone) to invite them to participate in the research. Among those contacted, 13 agreed to participate, 9 said no, and 40 did not respond (including people whose email addresses or phone numbers were not working). The first author conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews, including questions related to participants’ perceptions of the fairness and validity of the investigation process. Each interview lasted 30 to 60 minutes. Eleven participants allowed the interview to be audio recorded and transcribed. One participant requested no audio recording, so the interviewer took detailed notes. One participant submitted responses in a text document.

The first interviewer analyzed transcripts and notes using qualitative data analysis, including word coding to identify patterns of words, phrases and contexts within the transcripts and notes. He then identified common themes and subthemes within the answers to the primary questions (Grinnell et al., 2018). To enhance the rigor of the study and verify the accuracy of the themes, the third author conducted an external audit of the themes identified by the first author by reviewing each transcript and comparing participant data to the themes and subthemes generated (Creswell & Miller, 2000). The second author did not have access to the original data. He participated in writing the literature review and conclusions for this article.

Findings

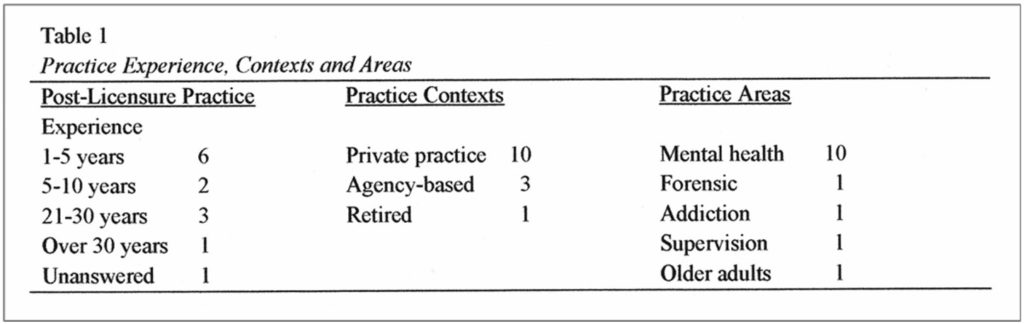

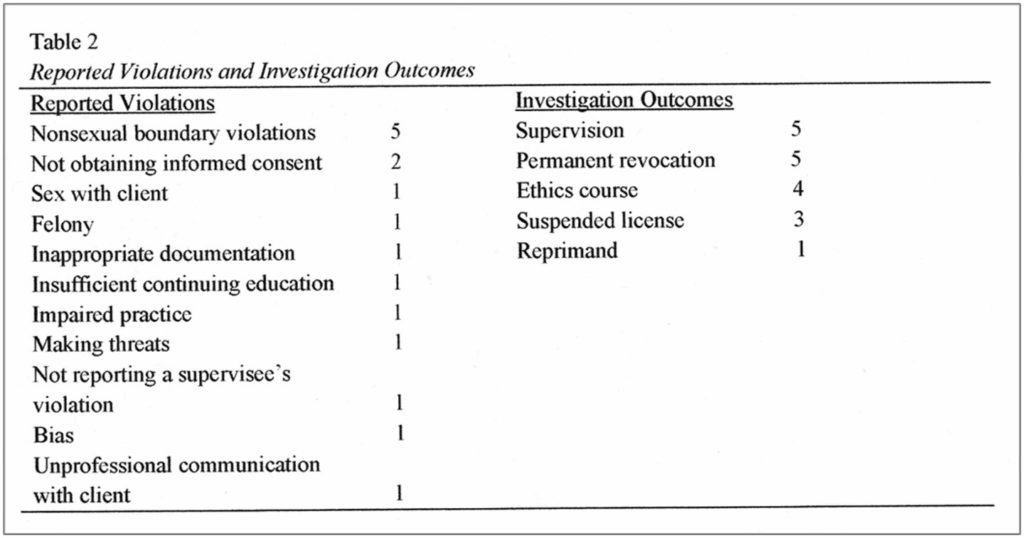

The sample included 11 female and 2 male LISWs who experienced investigations between 2004 and 2020. Tables 1 and 2 illustrate the demographics of the sample. In terms of post-licensure experience at the time of the investigation, 6 participants had 1 to 5 years, 2 had 5 to 10 years, 3 had 21 to 30 years, and 1 had over 30 years [one did not answer]. The participants’ practice contexts at the time of investigation included private practice (10), agency-based practice (2), and retired (1). Their primary practice areas included mental health (10), forensic social work (1), addiction (1), supervision (1), and older adults (1). The reported violations included nonsexual boundary violations (5), not obtaining informed consent (2), sex with client (1), felony (1), inappropriate documentation (1), insufficient continuing education (2), impaired practice (1), making threats (1), not reporting a supervisee’s violation (1), bias (1), and unprofessional communication with client (1). The investigation outcomes included, permanent revocation (5), supervision (5), ethics course (4), suspended license (3), and reprimand (1). Some LISWs received 2 consequences. Some demographic information cannot be reported to maintain the participants’ anonymity. The following sections describe the participants’ initial reactions to learning that they were being investigated, their experiences with the investigation process, and their perspectives on the value of obtaining legal representation.

Numbers in each column may not add up to 13 because more than one response may have applied to certain research participants.

Initial reactions

When participants learned that licensing complaints were initiated against them, their reactions ranged from shock, fear, and embarrassment to resignation or hope. Some participants were shocked or “dumbfounded” because they had never experienced prior complaints and they had no idea that clients, family members, or professional colleagues were planning to file complaints. Some participants were immediately afraid that they would lose their license and their ability to earn a living. As one participant noted, “I was scared to death. I opened the letter with some friends at a restaurant and couldn’t speak.” The stress levels were so great that participants found it difficult to respond to the allegations. Other participants felt embarrassed, understanding that they had violated a law or ethical standard. They felt badly about “screwing up” despite having good intentions. Some participants felt resigned and decided relatively quickly that there was no point in contesting the complaint. They would simply accept the Board’s determination, even if that meant losing their license and leaving the profession. Finally, some participants felt hopeful. They believed the board would listen to them and either dismiss the case or find a violation but impose a relatively minor consequence. Upon meeting with the investigator, however, those who felt hopeful quickly learned that they would likely face more serious consequences than they had initially expected.

Experiences with the investigation process

Three participants described having positive experiences with the investigation process. They felt the process was fair, the investigator treated them with respect, and the investigation was conducted in a timely manner. These participants acknowledged early on that they violated laws or ethical standards and decided not to contest the matter. Among the 10 participants reporting negative experiences, most contested the validity of the allegations. However, some felt the process was unfair or disrespectful even in cases when they acknowledged wrongdoing. The following subsections describe 5 key aspects of the investigation process from the participants’ perspectives: due process, respect, investigator neutrality, investigator qualifications, and contextual factors.

Due process

The three participants who felt the process was fair said they were made aware of the allegations against them, they had an opportunity to present their evidence, the investigator did not assume guilt, and the investigator offered them an opportunity to sign a consent agreement (admitting a violation) or proceed to a full hearing. These participants said they voluntarily admitted the violations and agreed to sign the consent agreement. Although two participants felt the consequences were harsh, all three appreciated the timely matter for handling the complaint.

Among the 9 participants sharing strong concerns about fairness of the process, some indicated that they were not told about the specific allegations and they were denied information that would have been useful to respond to the investigator. They noted that they were unprepared and caught off guard when they met the investigator. They felt that they should be afforded similar due process rights as if they were being tried in a criminal case. As one participant noted:

If there’s a criminal case… you’re provided with the evidence that somebody has against you, so you can defend yourself. If the prosecutor has this, that, or the other, you have some information. You can make decisions about how to proceed… Do you plead guilty, do you plead no contest, or do you just take it to trial? And when I asked for that information, they said you’re not privy to that.

Participants suggested that statutory provisions limited what information could be shared, including names of complainants and what specific evidence they had shared with the board. Although they understood why complainants’ names might be protected, the absence of this information made it impossible to respond to possible motivations behind the complaints. For instance, if a client made a complaint, the client may have been unhappy with services; if a family member made a complaint, the family member might have been upset that the worker was advocating for the client. Participants wanted access to the particular evidence being presented against them so they could have a fair opportunity to defend themselves. If complainants submitted particular documents, being able to see the documents would enable the worker to either contest the document or accept it as valid evidence.

One of the strongest concerns expressed by participants was that the investigator believed the complainant and assumed the participant was guilty even prior to the social worker having an opportunity to present evidence or explanations for their actions. Some believed the investigator acted on hearsay (second-hand information) and was not open to hearing anything from the participant’s perspective. One participant said the investigator relied on information from a family member and did not even speak with the client for first-hand information. Several participants felt the investigators lacked objectivity, assumed what the complainant said was true, and had their “mind made up” before the interview process. These participants felt the investigators treated them as if they were guilty even before they were even afforded a chance to provide evidence. One participant’s attorney explained, “This is administrative law. You’re guilty until you can prove your innocence.” One participant indicated that the investigator would not allow questions about the allegations or incriminating evidence. Various participants suggested that they had no opportunity to make their cases because the investigators had already made up their mind. One participant said, “I offered to show them the records. They said it didn’t matter. I showed them why I was concerned and why I did what I did. It didn’t matter.”

Some participants felt the investigators pressured them into signing consent agreements. “They just want an open and shut case.” Some participants said they were told to sign the agreement and that the consequences would be harsher if they requested a hearing. Some participants acquiesced because they wanted to end the process as quickly as possible or because they could not afford an attorney to represent them in a hearing. Others suggested that there was no point in requesting a hearing because the Board would simply rubber stamp the investigator’s decision. They did not think Board members would be any more willing to hear their evidence than the investigator. Two participants had hearings. Both suggested the hearing was unfair because the Board simply went along with what the investigator presented; they were not open to evidence or arguments presented by the participants. One participant appealed the consent agreement, suggesting it was not a true agreement. The participant said the Board moved to enforce the agreement despite the objections. They would not allow the participant to renegotiate the agreement or conduct a fair hearing.

Some participants suggested the Board should not initiate investigations of concerns raised by professional colleagues unless and until the colleague first tried to resolve matters informally with the subject of the allegation. They suggested this prerequisite would fit with Standard 2.10(c) of NASW Code of Ethics and also offer them an opportunity to understand the nature of the allegations. They felt it may also deter false allegations.

Some process concerns were identified by a single participant. One participant questioned the integrity of how information was gathered. The participant said the investigator called work colleagues, pretending to be someone else in order to gather incriminatory evidence. The participant suggested that, when gathering evidence, investigators need to identify themselves and their purpose for calling. Other participants expressed concerns that there was no opportunity to delay hearings due to personal or family hardships, including illness or death. One participant felt the Board could have accommodated the participant. The Board’s decision forced the participant to attend despite having a compromised ability participate effectively in the hearing. The participant also had to choose between attending to family concerns or attending the hearing.

Respect

Three participants indicated they were treated with kindness and respect. They felt the investigator was nonjudgmental and professional. The investigators acted in a matter-of-fact manner and focused on the allegations in a professional manner. They allowed the participants to speak openly and ask questions. The participants did not feel that they were being treated as “bad” people. One participant expressed gratitude about an investigator showing empathy for the personal challenges experienced by the participant.

For the nine participants who felt the investigator treated them with disrespect, the main concerns were that the investigator grilled them, used judgmental language, and facilitated an intimidating process. By grilling, some participants suggested the investigators acted like criminal law investigators trying to get them to present incriminating evidence and admit violations. Some felt the investigators used interrogation for “power and control.” One described feeling “pounded by questions” and pressured to admit particular violations. Another stated, “They brought me in and it was basically gestapo grilling for two hours.”

Some participants felt the entire structure was intimidating, from having to drive several hours to the investigator’s office, to lack of parking, to having their pictures taken by security upon entering the building, to being forced to wait alone. Some knew of colleagues who met with investigators on neutral territory closer to where they lived. They expressed distress about why they were being set up for a more intimidating process. One participant expressed concerns that the investigator scheduled their interview at a restaurant. Although the location was neutral and convenient, it was not a private or confidential setting.

Various participants expressed concerns about the investigators’ training, suggesting investigators were trained in criminal law and interrogation. They believed investigators should be trained with social work skills such as empathy, respect, neutral fact finding, and holistic assessment. Some felt the investigator was very argumentative, for instance, telling them what they should have done or should have known. One described the investigator as “a pit bull” whose mind was made up from the outset. Another suggested the investigator’s hostility was projected through an angry tone of voice, phraseology, and attitude.

Some participants suggested investigators intimidated them by raising their voices or standing over them with threatening body language. One participant said, “She was just going after me. She was never friendly. From the outset, from the greeting. She was not congenial or collegial at all. She was just on me.”

One participant said that when she answered questions the investigator would yell, “That’s not what happened.” She wondered why the investigator asked questions if she did not want to hear the answers. A participant who described the overall process as “fair,” described the investigator as “hostile and antagonistic.”

Some participants expressed concerns about the investigator’s cold tone and adversarial style of questioning. One participant noted, “It was like a trial, so I was pretty much questioned about everything that happened in the incident. It was very cold… Very judgmental… The way [she] asked questions and made me feel like a repeat offender.”

Examples of questions viewed as curt or disrespectful included, “Didn’t you know better?” or “Didn’t you know you committed a conflict of interest?” Participants suggested these questions were meant to intimidate or demean rather than to gather information. The investigator’s questions and tone suggested the participants were “creepy” or “scummy.”

Various participants said investigators used language and tones insinuating the participants were terrible people, the equivalent of sexual predators or heinous criminals. Concerns about judgmental language were raised by participants who readily admitted they messed up, as well as by those who believed they did nothing wrong. Some mentioned that the investigator’s interrogations and insinuations made them feel sick or brought them to tears. Others felt they could not open their mouths without getting into further trouble. One mentioned that she was initially prepared to disclose additional violations, but then felt too intimidated to be open and honest with the investigator.

Some participants said the investigator lacked empathy, not acknowledging their feelings or experiences. Some participants recently experienced death, illness, or separation in their families, but the investigator showed no compassion. They felt the process was punitive, as investigators did not demonstrate concern for their hardships or wellbeing. Some participants suggested that investigators could have acknowledged that the client and worker could have different perceptions of what happened rather than dismissing the worker’s perceptions.

Participants expected the investigators to be friendlier and more respectful. When one participant expressed concerns about the investigator’s approach, the investigator said, “Look, you don’t understand this. I’m not your friend. I’m not here to help you.” The participant said she stopped and started to cry. “What a terrible thing to say.”

Participants knew that investigators were not their friends; however, they expected the investigators to be respectful and supportive rather than degrading.

Investigator neutrality

Participants believed that it was important for investigators to have and to demonstrate neutrality throughout the investigation process. Although some participants felt that investigators conducted unbiased investigations, others suggested that investigators operated on various biases. Some felt that investigators were biased toward clients or family members who initiated complaints, assuming their allegations were true. These participants did not feel they had fair opportunities to be heard. They suggested investigators asked leading questions and were not interested in unbiased information gathering. As one said, “I’m guilty because I am accused.” They said investigators ignored the fact that some complainants had personality disorders or other mental health conditions that led to dubious complaints. One participant said, “I felt like I was being accused and prosecuted for things that were inaccurate. I was dumbfounded by how closed-minded the investigator was. They took the word of one person over 30.”

Some participants believed investigators were biased against women and that women receive harsher treatment than men. Other participants felt that investigators had biases based on their type of practice or methods of intervention. Participants working in custody cases or high-conflict family situations, for instance, suggested that investigators said they should not be practicing in those areas. These participants acknowledged working with clients who may be more likely to initiate complaints; still, they felt that investigators should not treat them more harshly because of their practice areas. Some participants indicated that investigators lacked objectivity regarding nontraditional models of practice; that is, investigators assumed that participants committed malpractice simply because they employed naturopathy or non-Western approaches to health and mental health. They suggested investigators were not open to hearing about the positive effects of their methods. Some participants noted that investigators treated them as “evil” because they used alternative medicine or other nontraditional approaches.

Contextual factors

Some participants felt the process was unfair because the investigator did not consider contextual factors, including the participant’s past conduct, the impact of the alleged violation on the client, the participant’s intentions, and the motivations of the complainant. Participants believed the investigator should have gathered information about the participants’ past conduct, including all the good work and positive impact they had with their clients and communities. After many years of exemplary service, they felt they should not be punished harshly for a single “questionable act” or “lapse in judgment.” Some believed that suspending or revoking their licenses would do more harm than good, so it was vital to assess alleged violations in context.

Participants noted that investigators did not seem interested in the impact of alleged violations on their clients. In situations of alleged boundary violations or dual relationships, for instance, they noted that the client did not suffer or that the client actually benefited from the conduct in question. If there was no harm to the client, how could there be a violation? In the words of one participant, “Although there was a conflict of interest, which I agreed, there was no harm. I acted ethically.”

Participants also expressed concerns that investigators did not take their intentions into account. They suggested that if they crossed a boundary or did something out of their ordinary scope of practice, they meant well. As one participant stated, “I told [the investigator] all the good things that I did for my client… And she said, ‘Your intentions mean nothing.’ And I about fell off my chair, because my intentions mean everything to me. Everything. When I intend for a client to get better, I will do whatever needs to be done.” Participants were concerned that investigators did not seem to care about their intentions when their intentions and the outcomes for the client were positive.

Some participants said investigators would not consider the motives of complainants. Although investigators did not disclose names of complainants, some participants surmised that family members initiated the complaints. They believed the clients were happy with the services but family members were unhappy with the social worker for acting as an advocate for the client. They felt family members may not like that workers advocate for what the client wants rather than what the family wishes. Other participants thought that a begrudged colleague initiated the complaint. One participant stated, “It’s a retaliatory complaint. I knew my partner was behind it. I knew my client appreciated what I did.” Participants expressed concerns that investigators did not want to hear why the colleague may have initiated the case in bad faith.

Legal representation

Some participants decided to hire attorneys shortly after receiving notice of the investigation. Most had liability insurance covering legal costs. One did not have insurance and personally paid for legal fees. Participants who hired attorneys felt it was important to have legal representation because their license and livelihood were at stake. Some participants did not hire an attorney until after their first meeting with the investigator. Some thought the process would be relatively informal and swift, so they did not need attorneys. Some participants believed the allegations would be dismissed as soon as they presented their side of the story. As one noted, “You don’t go to the investigator’s office and answer questions without an attorney. It all seemed so innocent. I thought you could just go there and explain what happened and it will be ok.”

Participants decided to “lawyer up” when they felt the investigator was not treating them fairly or when they feared harsh consequences were impending. Some participants felt investigators gave more credence to arguments presented by attorneys than they would have received without an attorney. Participants noted the importance of having an attorney who specialized in licensing cases. One participant suggested that having a prior relationship with board members helped the attorney negotiate more favorable results.

Some participants decided not to hire attorneys because they did not intend to contest the case. Others declined legal representation because they did not have insurance and could not afford the legal fees. They received estimates that legal fees would surpass $10,000—and much more if the case went to court. Among these participants, some quickly agreed to have their licenses revoked, thinking there was no point in contesting the allegations without the aid of an attorney. Others contested the allegations but felt that they were at a disadvantage without an attorney. Participants noted that it was particularly expensive to pay for attorneys who had to drive long distances to attend investigation meetings or hearings.

Among those who hired attorneys, perceptions of the value of legal representation varied widely. Those who valued legal representation appreciated having the attorney explain the process, provide them with reassurance, and defend their rights. In the words of one participant,

My lawyer did a much better job explaining the process than the investigator did. He said, “The investigators are like your parents, and you’re like a 16-year-old and you get in a car accident. It’s no use saying the car was old or it wasn’t your fault. Just bow your head and apologize profusely, and things will go better for you.” That spoke to me. I understood my position. So, I said, “I’ll bow my head and learn my lesson—no excuses.”

In some instances, participants originally believed that they did not violate any laws, but attorneys were able to help them understand that they had done so. In some cases, attorneys took responsibility for communication with the board. Several participants felt the attorneys negotiated better consequences than they could have done themselves (e.g., reducing the period of a suspension). Some participants also appreciated that their attorneys demonstrated care and concern for how they were feeling and coping.

Certain participants believed that hiring an attorney led to investigators becoming more defensive, more adversarial, or more punitive. They noted changes in the investigator’s demeanor, describing instances when investigators bristled or raised their voices. One participant suggested the investigator brought the Board’s director into meetings because she had an attorney. Another suggested that the investigator allowed the attorney to be present but would not permit the attorney to speak: “They literally told him to shut up.” Another participant suggested that hiring an attorney led investigators to think the participant was admitting guilt. “Having a lawyer may have made it look like I was guilty. Otherwise, why would I need one?”

Participants who contested whether they violated any laws tended to have more concerns about involving attorneys than those who were willing to admit fault. When attorneys were primarily negotiating consequences, participants felt that having an attorney was particularly helpful. When participants hired attorneys to contest the allegations, they often felt the investigators became more antagonistic and punitive.

Limitations

Given that this study was based on a sample of 13 participants from one licensing board, the primary limitation is the transferability of the findings (Grinnell et al., 2018). Although the sample was drawn randomly from a list of LISWs who had received licensing sanctions, the sample may be skewed by the fact that nine people declined to participate in the research and 40 others did not respond to calls or emails (including the possibility of incorrect email addresses or phone numbers). People with stronger feelings about the process may have been more likely to respond. People who felt embarrassed or anxious about their investigation experiences may have been more likely to decline participation. Others may have felt they had nothing important to share regarding their experience. Still, the sample generally reflected the demographics of the Ohio Counselor, Social Worker, and Family and Marriage Therapist Board’s cases in relation to gender, agency-based versus private practice, practice areas, and the range of violations. The findings may be more transferable to licensing boards with similar investigation processes to those of Ohio (e.g., paid professional investigators rather than board members or licensed volunteers recruited by the board).

Discussion

Feedback from research participants suggests the investigation process comprises 5 essential elements: due process, investigator qualifications, respect, investigator neutrality, and contextual factors. In terms of due process, participants believe it is important for LISWs to have access to the specific allegations and evidence submitted by the complainants. They believe that they needed this information to have a fair opportunity to defend themselves. They think they should be treated as innocent until violations were proven and investigators should avoid suggestions of guilt throughout the investigation process. Some participants compared licensing investigations to criminal court cases, expecting to be provided with the same rights as a person charged with a crime. Given this feedback, licensing boards should consider what types of rights or due process protections should be afforded to LISWs under investigation (Williams, 2001). Some changes may be made by updating internal policies; other changes may require reforms to licensing statutes or regulations. Licensing investigations are different from criminal prosecutions, so boards should ensure that LISWs fully understand their procedural rights and how these rights may differ from those in criminal proceedings. According to the principles of due process, LISWs should have a right to know the specific allegations against them, a right to a timely process, and a right to provide their evidence and arguments to an impartial investigator before the investigator determines whether any violations have been committed. Investigators should inform LISWs about the standard of proof used to determine violations (Van Horne, 2004). Boards should ensure that they provide LISWs with clear information (in writing and orally) regarding the nature of the investigation process, their right to a hearing, and the implications of signing a consent agreement. Some participants in the present research said they did not understand that they were waiving all their rights and could not have a hearing once they signed a consent agreement. Boards should also institute methods of gathering feedback from LISWs so they can ensure the investigation process is fair and can take corrective actions when necessary.

When laws prevent investigators from sharing certain information with LISWs, investigators should provide clear explanations so LISWs can understand why such information is unavailable. Policymakers might also consider ways to allow protected information to be shared upon consent of the complainant. For instance, if a complainant agrees to share particular documentation, then this information could be shared with the licensee.

In terms of investigator qualifications, investigators should be skilled at gathering information in a fair, respectful, and impartial manner (Gricus, 2018). Participants noted the importance of using body language, verbal skills, and vocal tones to convey respect. Leading questions, for instance, may cause LISWs to believe that investigators predetermined the LISW committed the alleged violations. The use of stern tones may suggest the investigator is angry or disappointed with the licensee. Participants felt investigators should be trained to demonstrate empathy, compassion, and unconditional positive regard just as social workers afford these qualities to their clients. Investigators should be aware of any negative feelings toward licensees so they do not allow these feelings to interfere with the need for neutrality and respect.

Participants understood the value of having legal representation, but some felt that investigators responded angrily or defensively when they brought attorneys into the process. It is important for investigators to support the use of attorneys (Williams, 2001). Boards may need to offer investigators training and support on how to work effectively with attorneys.

Some participants believed that boards should take contextual factors into account; for instance, their prior history of professional service, their good intentions, and personal and familial concerns that they were experiencing. Licensing laws typically do not allow these factors to be considered when determining whether violations have been committed. These factors could be considered in terms of the consequences for violating licensing laws. A licensee who had good intentions and a prior history of stellar practice, for instance, may be provided with corrective actions for relatively minor violations. Suspensions and revocations should be reserved for the most serious violations. Boards should educate LISWs about what types of factors are considered in determining violations, as well as what types of factors are considered when determining appropriate consequences. Investigators should also be trained to validate concerns expressed by LISWs, even if the concerns are not directly relevant to the decision about whether a violation has occurred. When LISWs describe their good work, their good intentions, or personal hardships, they would appreciate empathy and compassion. They view licensing boards as part of the social work profession. They feel betrayed by the board when investigators come across as uncaring or judgmental. They believe that boards should be supportive and offer corrective actions rather than punitive ones.

Conclusion

Licensing investigations are stressful processes. LISWs fear for their livelihoods and reputations. LISWs may benefit from greater guidance about working with licensing boards, including how to advocate when they believe investigators are acting in an inappropriate manner. Whenever social workers receive notice of a complaint from their investigatory bodies, they should obtain legal consultation. Experiences from the research participants suggest that contacting an attorney early is vital to understanding the nature of the allegations, potential consequences, and the best course of action moving forward. When seeking legal representation, social workers should consider attorneys who specialize in licensing complaints and are familiar with the investigation process. Attorneys can provide suggestions for how to respond to the licensing body, including how to respond in writing and how to prepare for meetings with the investigator. Some participants noted that costs were a barrier to hiring an attorney. Thus, it is important for social workers to have professional liability insurance that covers the cost of legal advice and representation to assist with any licensing complaints. Social workers under investigation may also benefit from consultation with another social worker who has specific training and experience related to the issues under investigation. Specialized consultants can assist the social worker in identifying any past concerns about their practice, as well as helping the worker take corrective action to ensure safe, effective, and ethical practice moving forward.

In terms of continuing education, LISWs may benefit from further education about the types of cases that come before licensing boards, as well as the types of consequences issued by the boards for various types of misconduct. Trainers or practitioners could consult the National Practitioner Data Bank to obtain information about malpractice cases and other adverse actions against social workers and related professionals in the fields of health and mental health. Although information about cases filed may be confidential, state licensing boards do publish information in cases that have resulted in a finding of misconduct. Learning about specific cases may help LISWs appreciate the nature and severity of recent complaints.

The present research focused on the views of LISWs who experienced investigation processes. Future research could compare the perceptions of LISWs with those of investigators, complainants, and attorneys who participate in investigation processes. It would also be instructive to compare perceptions of investigation processes in different states (Krom, 2019). Historically, licensing boards may have shied away from opening their processes to researchers due to concerns about confidentiality, as well as concerns about responding to negative feedback. Although confidentiality is certainly important, these concerns can be managed through informed consent and ensuring that findings are presented without identifying information (Barsky, 2019). Licensing boards play a key role in promoting ethical practice and investigating the validity of complaints against licensees. Given the potential impacts of investigations for LISWs and the people they serve, it is vital that boards ensure their processes are fair, safe, and constructive.

References

Association of Social Work Boards. (n.d.). About licensing and regulation.

Barsky, A. E. (2019). Ethics and values in social work: An integrated approach for a comprehensive curriculum (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Boland-Prom, K. (2009). Results from a national study of social workers sanctioned by state licensing boards. Social Work, 54(4), 351-360.

Boland-Prom, K., Krcatovich, M., Wagner, S., & Gilbert, M. C. (2018). Social work educators’ evaluations of regulatory boards. Journal of Social Work Values & Ethics, 15(2), 81-92.

Boland-Prom, K., Johnson, J., & Gunaganti, G. (2015). Sanctioning patterns of social work licensing boards, 2000 to 2009. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(2), 126-136.

Carnahan, B. (2019). Examining professional licensure risks. Risk Management, 66(3), 18-20.

Chase, Y. E. (2015).Professional ethics: Complex issues for the social work profession. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(7), 766-773.

Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into practice, 39(3), 124-130.

Daley, M., & Doughty, M. (2007). Preparing BSWs for ethical practice: Lessons from licensing data. Journal of Social Work Values & Ethics, 4(2), 3-9.

Gricus, M. (2018). “Of all the social workers … I’m the bad one:” Impact of Disciplinary Action on social workers. Social Work Research, 43(1), 5-16.

Grinnell, R. M., Williams, M., & Unrau, Y. A. (2018). Research methods for social workers: An introduction (12th ed.). Pair Bond.

Krom, C. L. (2019). Disciplinary action by state professional licensing boards: Are they fair? Journal of Business Ethics, 158(2), 567-583.

Ohio Counselor, Social Worker, and Family and Marriage Therapist Board. (n.d.). https://cswmft.ohio.gov

Peterson, M. B. (2001). Recognizing concerns about how some licensing boards are treating psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32(4), 339-340.

Schoenfeld, L. S., Hatch, J. P., & Gonzalez, J. M. (2001). Responses of psychologists to complaints filed against them with a state licensing board. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32(5), 491-495.

Strom-Gottfried, K.J. (2003). Understanding adjudication: The origins, targets and outcomes of ethics complaints. Social Work. 48(1), 85-94.

Strom-Gottfried, K.J. (2000a). Ensuring ethical practice: An examination of NASW Code violations, 1986-1997. Social Work, 45(3), 251-261.

Strom-Gottfried, K.J. (2000b). Ethical vulnerability in social work education: An analysis of NASW complaints. Journal of Social Work Education, 36(2), 241-252.

Thomas, J. T. (2005). Licensing board complaints: Minimizing the impact on the psychologist’s defense and clinical practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(4), 426-433.

Van Horne, B. A. (2004). Psychology licensing board disciplinary actions: The realities. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35(2), 170-178.

Wilkinson, T., Smith, D., & Wimberly, R. (2019). Trends in ethical complaints leading to professional counseling licensing boards disciplinary actions. Journal of Counseling and Development, 97(1), 98-105.

Williams, M. H. (2001). The question of psychologists’ maltreatment by state licensing boards: Overcoming denial and seeking remedies. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32(4), 341-344.