Archives > Volume 18 (2021) > Issue 1 > Item 08

DOI: 10.55521/10-018-108

Josphine Chaumba, Ph.D.

Valdosta State University

jchaumba@valdosta.edu

Alice K. Locklear, Ph.D.

University of North Carolina at Pembroke

alicek.locklear@uncp.edu

Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics • Volume 18(1), Copyright 2021 by ASWB

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of ASWB.

Abstract

This article reports the results of a systematic literature review that sought to understand strategies used by social work practitioners to promote client self-determination. The results showed that practitioners are using a variety of strategies that range from giving clients voice or choice to integration of best practices including elements of self-determination theory, shared decision making, or the Lundy Model. Further analysis of the strategies suggested that they could be enacted at two key stages that include worker-client interactions and the organizational level. Both agency administrators and practitioners have essential roles to play in defining and implementing processes that can promote self-determination in social work settings.

Keywords: client self-determination, social work practice, promoting self-determination

Increasing threats to client self-determination in social and health care settings call for agency and practitioner facilitated strategies to bolster this basic client right. Kirst-Ashman and Hull (2018) observed that in the United States managed care has shifted decision making from practitioners and clients who now experience “significantly decreased choice” to third-party case managers or utilization reviewers who define services implemented during treatment (p. 148). Furthermore, constraints to client self-determination are imposed by involuntary client statuses of service users, limited resources, funding requirements, program logistics, and apparent power imbalances between service providers and client groups. These constraints may cause service providers to become more focused on meeting their work obligations without due consideration to dynamics that may deny clients opportunity to influence decisions regarding their care (Rooney & Mirick, 2018; Wolfer, Hodge, & Steele, 2018). For instance, interviews with 151 adolescents aged 16 to 20 who had been in child welfare protective custody for at least 12 months revealed that only 7% of the youth felt that their level of personal involvement in the decisions made about their case matched what they desired, and 64% desired more involvement suggesting the need for clear guiding policies on how to involve youths in decisions regarding their care (Beal et al., 2019). Given practice realities that stifle client self-determination, service providers need to be intentional and innovative to promote its implementation.

This article presents results from authors’ systematic literature review investigating strategies used by social work practitioners to support client self-determination, as reported in published social work literature. We attempted to uncover processes that social service professionals are using to promote client self-determination and to point out knowledge that is valuable for developing tools that could guide client participation in making decisions about their care. This analysis may also help orient novice social workers and students to practice models and processes that support client self-determination. In the following sections we present a summary of the existent literature on definitions and models of client self-determination, describe our methods, share results of the literature review, discuss major implications, and conclude by noting limitations in this study and directions for future research.

Conceptual Definition of Client Self-Determination

We have identified two main conceptualizations of client self-determination in the social work literature. The first conceptualization views self-determination as an ability that clients possess or a basic right for clients to make independent choices about their care without external coercion. For instance, Hepworth, R. H. Rooney, G. D. Rooney, Strom-Gottfried, and Larsen (2010) wrote that self-determination means that “clients have the capacity to develop solutions to their difficulties, as well as the right and capacity to exercise free choice responsibility” (p. 63). When upholding client self-determination social workers are showing “respect for individuals’ abilities to make their own decisions regarding life’s alternatives” (Abbott, 1999, p. 438). The main limitation of this first conceptualization of client self-determination is that the capacity to make independent decisions regarding one’s care is sometimes impossible due to organizational policies such as when an agency subscribes to a particular model of care limiting allowable activities, due to crisis situations, and in some cases due to client characteristics such as health status, disability, and age. For this reason, a broader view of client self-determination as a process with careful planning becomes necessary.

Hence, the second major conceptualization views client self-determination as a process for ensuring client participation through the different stages of their treatment or services (Barsky, 2019). For instance, within the context of transition to adulthood for teenagers with varying abilities, Wheeler, Lyle, Arnold, Williams, Imagawa, and Kim (2016) defined self-determination as “an individual participating actively in defining what she or he wants to do and how to get there” (p. 210) with the social worker providing needed support instead of taking over the decision making. When client self-determination is viewed as a process, service providers implement ongoing strategies that increase “transparency in decision making , collaboration… accountability, humanity and justice” even in the exercise of legal mandates that child protection workers have to enforce to promote the welfare of clients in their care (Healy, 2000, p. 75, 76).

For the purposes of this article, then, client self-determination is conceptualized as a collaborative process that social service agencies and practitioners make available to their clients to express clients’ values and preferences in order to shape decisions regarding clients’ treatment, care, and services. This process requires intentional ongoing mechanisms by agencies and practitioners that allow clients to be partners in influencing decisions made about their care. Kosko (2013) identified multiple points of entry that organizations and practitioners can offer to clients to facilitate participation in the decision making process with the earliest entry point being at the problem definition and diagnosis stage, followed by selection of possible responses to the identified problem, selection of one course of action, implementation of that chosen course, and evaluation of the course of action. While the entry points suggested by Kosko are common elements of the social work process, specific strategies that social workers are using to promote client self-determination need further exploration.

Models and Processes that Foster Client Self-Determination

The National Association of Social Workers’ Code of Ethics clause 1.02 identifies self-determination as a key guiding principle in social work practice (NASW, 2017). Although NASW does not provide specific procedures for promoting client self-determination, models and processes guiding its current implementation are reported in the literature. Following a systematic review of the literature, Kennan, Brady, and Forkan (2018) found that common strategies used to promote participation among children and youths in child welfare included child protection meetings, family welfare conferences, and care planning and review meetings. Gambrill (2013) articulated practitioner initiated strategies that can be used to partner with clients in the self-determination process through open acknowledgment and “discussion of any coercive aspects of contact between social workers and clients, focusing on outcomes that clients value whenever they do not compromise the rights of others, clearly describing goals and methods, and involving clients in decisions made” (p. 47).

While the aforementioned provide general guidelines that could promote client self-determination, conceptual models that identify specific factors that can be used to foster clients’ capacities to participate meaningfully in the self-determination process are also reported in the literature. These models are (a) Self-Determination Theory, (b) Shared Decision Making, and (c) the Lundy Model of Participation.

(a) Self-Determination Theory (SDT). SDT’s mini-theory of Basic Psychological Needs proposes that humans need social environments that recognize their basic psychological needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy in order to achieve full functioning and wellness (Gagné & Deci, 2014, p.4). Of particular relevancy to client self-determination is the need for autonomy defined as the extent that clients feel that their experiences and actions are consistent with their genuine interests and values (Ryan & Deci, 2017, p. 10). In particular, meeting the need for autonomy would have direct influence on promoting client self-determination as the practitioner co-creates an environment where the client’s interests and values are explored and integrated into the treatment plan. Sheldon, Williams and Joiner (2008) suggested that practitioners demonstrate autonomy support by “acknowledging the clients’ perspective, giving the client as much choice as possible and providing meaningful rationales when choice provision is impossible” (p. 6).

(b) Shared Decision Making (SDM). The second conceptual framework guiding implementation of client self-determination is shared decision making (SDM) “a process in which clinicians and patients work together to make decisions and select tests, treatments and care plans based on clinical evidence that balances risks and expected outcomes with patient preferences and values” (National Learning Consortium, 2013, Paragraph 1). A key commonality between SDT and SDM principles is their alignment with the value of self-determination and emphasis on the importance of collaborating and supporting clients to make independent decisions. The main difference between the two is that SDM involves the use of specific tools that clients and practitioners review or develop together. Specific SDM aids include brochures, videos, and print materials that clients are given to read or watch followed by a discussion with the provider to aid with the decision making (Elwyn et al., 2010, p. 971). Other examples of SDM informed interventions used in mental health are joint crisis planning and advance directives (Slade, 2017). Guidelines on how to implement SDM are evolving in social work. Cummings and Bentley (2014) discussed decision making tools that social workers can use in health-related settings. Peterson (2012) provided a case study on how social workers in primary care settings can apply SDM. In this case study, Peterson recommends the use of SDM aids as resources for clients to use to broaden their knowledge before they are engaged in discussions to explore how the proposed interventions fit into their cultural values and preferences as they decide on the best fit. Although there is some support for using SDM in social work (Levin, Gewirtz, & Cribb, 2016; Lukens, Solomon, & Sorenson, 2013), practitioners may still hold contrasting views on its usefulness because of its vague operationalization contributing to “confusion and frustration” in its application in social work (Levin et al., p.519). In addition, critical challenges threaten the implementation of SDM, such as ready access to evidence-based treatment models and decision aids, as well as developing and maintaining a supportive organizational culture that allows for meaningful client engagement (Elwyn et al., 2010; Slade, 2017).

(c) the Lundy Model of Participation. The final model guiding implementation of client self-determination is the Lundy Model of Participation in which practitioners are encouraged to apply the four concepts of space, voice, audience, and influence espoused in Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child to ensure participation by children in the decision making process (Lundy, 2007). Children must have a safe space, voice to facilitate an expression of their views, an audience to listen to their views, and influence as their views are acted upon as appropriate. Successful implementation of the Lundy Model of Participation may give children real opportunities for involvement in decisions regarding their care (Parkes, 2013).

In sum, even though guidelines for implementing client self-determination exist in social work, contexts through which the principle is enacted vary (Barsky, 2019). This systematic literature review pooled together strategies from various social work contexts to put together a comprehensive portrait of strategies for enhancing client self-determination in social work.

Methods

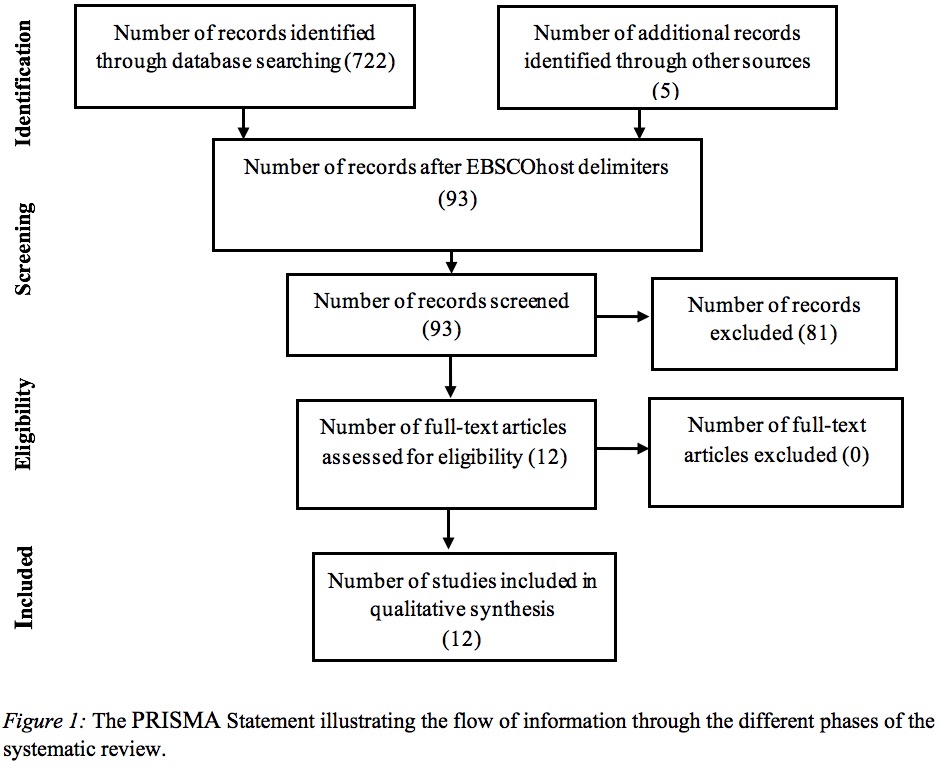

A keyword search was conducted in Social Work Abstracts, PsycINFO, Academic Search Ultimate, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and SocINDEX in May and June 2019 using “social work and self-determination, shared decision making, and client self-determination” as the search terms. The search yielded 722 articles that were first screened using the delimiters or criteria available in EBSCOhost to narrow down the search. Specific criteria that were used included filters such as empirical research, qualitative, quantitative, and peer-reviewed which left 88 eligible articles. Additionally, five articles, including one dissertation, were identified through analyses of reference sections resulting in 93 data sources. Abstracts and methods sections of the 93 studies were read. During this stage, studies (81) that focused on scale development, used student samples, were conceptual, or solely reported literature reviews were excluded from the study. Twelve studies that had used practitioner samples and agency-based reports or minutes of practitioner activities were included for further review. Figure 1 is a flow diagram called a PRISMA statement showing this selection process, as recommended by Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, and The PRISMA Group (2009).

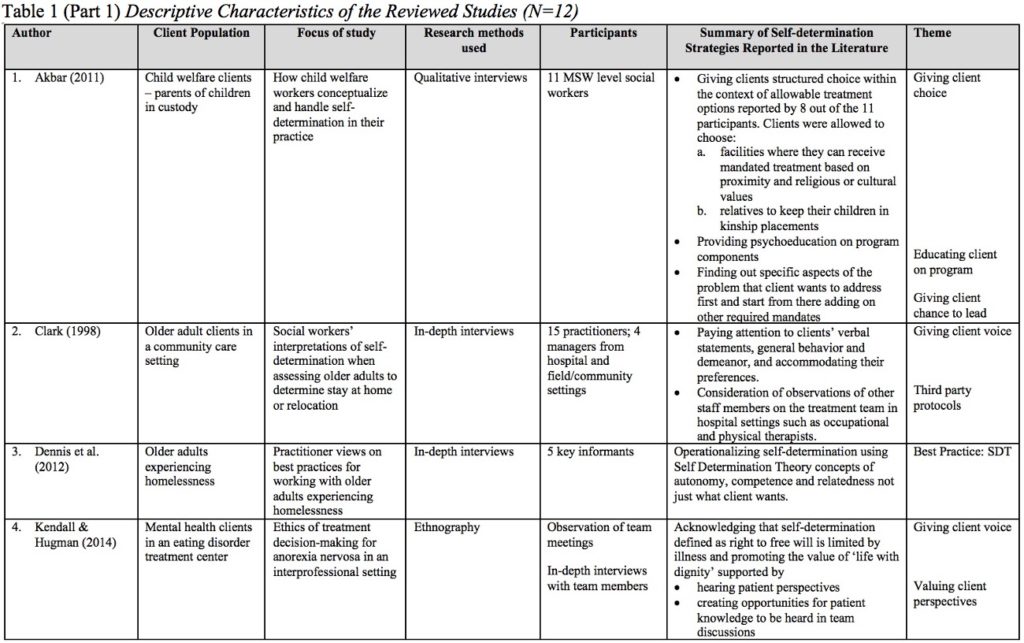

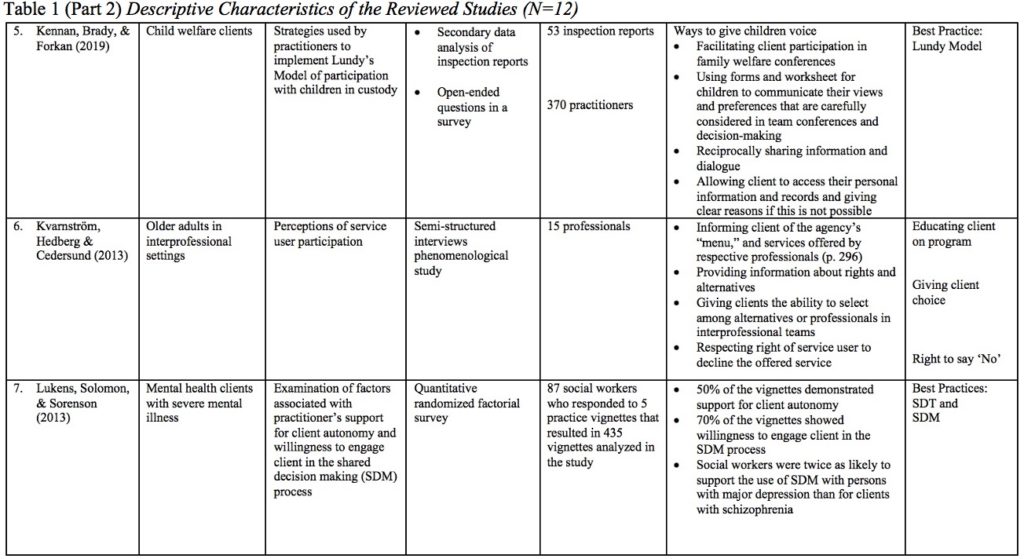

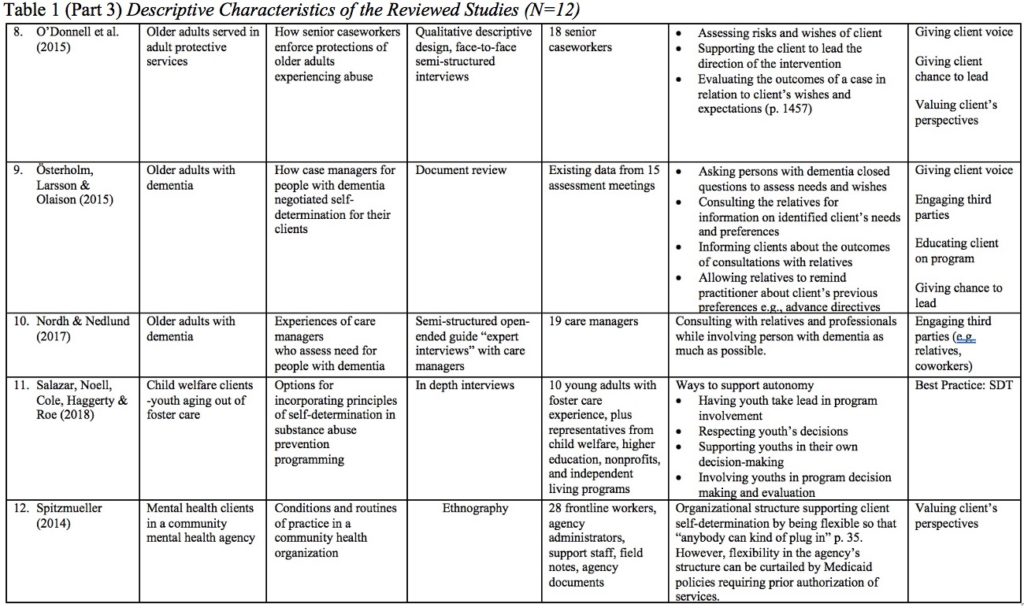

We then read the full text of each of the twelve selected studies; we used a data extraction form to capture information on the authors, client population, participants, and reported strategies for ensuring client self-determination as shown in Table 1. The reported strategies were further categorized to identify main themes and whether or not they were best enacted at the practitioner or organizational level. After completing the data extraction form, we performed frequency counts to determine the type of client population reported in the studies, type of research methods used, and strategies of client self-determination. Additionally, a narrative synthesis was done to organize and identify strategies used by social workers to promote client self-determination based on recurrent themes observed across the studies that we reviewed (Pope, Mays, & Popay, 2007). We both performed the literature identification and analyses. Inter-rater reliability for identifying themes and categories was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the combined total of agreements and disagreements between each of us, as suggested by McAlister et al. (2017). A value of 0.77 was obtained, which suggests satisfactory agreement in the identified themes and categories.

Results

The systematic literature review examined strategies used to promote client self-determination in social work practice. A descriptive summary of the reviewed studies is presented, followed by the key themes related to the identified strategies.

Descriptive Characteristics of Reviewed Articles

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of the reviewed 12 studies. The majority of the studies were qualitative (n=10), one was quantitative, and one used mixed methods. The most common client populations represented in the reviewed studies were older adults reported in six out of the twelve studies (50%), child welfare clients (25%), and mental health clients (25%). All the reviewed studies reflected conceptualizations of client self-determination that reflected uncoerced expressions of clients’ preferences and wishes and integration of intentional supports provided by practitioners to facilitate the process. For instance, in the study by Clark (1998) practitioners in the study listened to verbalizations of client preferences and also solicited feedback from other practitioners on their teams to gauge the extent of client self-determination.

Strategies for promoting client self-determination

The findings revealed diverse strategies that practitioners are using to promote client self-determination. Further examination of the reported strategies revealed two main levels at which the identified strategies are enacted: (a) the worker-client interactions and (b) the organizational level.

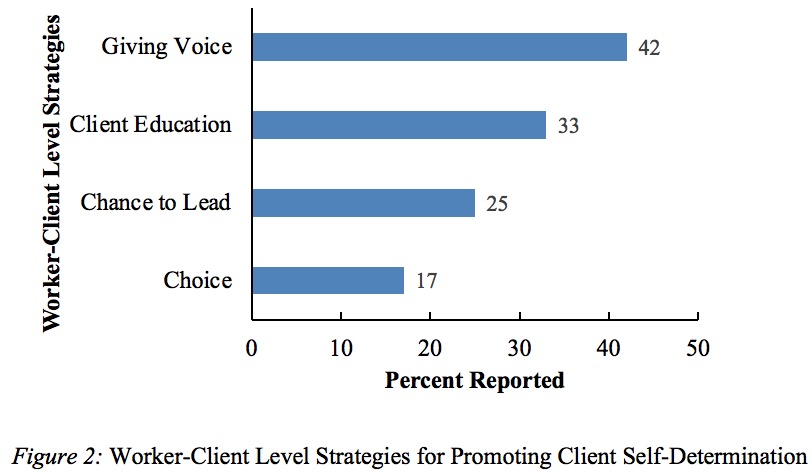

(a) Strategies at the Worker-Client Level. Figure 2 shows specific strategies that were categorized as occurring at the worker-client level.

Giving clients voice involved actions such as “hearing patient perspectives and creating opportunities for patient knowledge to be heard in team discussions” (Kendall & Hugman, 2014). Additionally, clients were invited to communicate their views and wishes during assessments and during treatment through reciprocal information and dialogue, the use of worksheets and forms, and practitioners’ careful consideration given to clients’ verbal communication, behavior and demeanor (Clark, 1998; Kennan, Brady, & Forkan, 2019; O’Donnell, Treacy, Fealy, Lyons, & Lafferty, 2015; Österholm, Larsson & Olaison, 2015). Client education covered broad areas such as program components (Akbar, 2011), the menu of services provided by the agency and alternatives (Kvarnström, Hedberg, & Cedersund, 2012), education on reasoning for particular treatment decisions (Kendall & Hugman, 2014), and expected outcomes (Österholm et al., 2015).

Giving client choice occurred when practitioners informed clients of possible treatment options allowable within their practice context for clients to choose, such as through the notion of structured choice in which parents were encouraged to choose facilities where they could receive the mandated trainings based on proximity, religious or cultural values (Akbar, 2011). Choice was also offered when clients were given information on their rights and alternatives with the ability to select among alternatives or professionals in inter-professional teams (Kvarnström et al., 2012). Giving clients a chance to lead their treatment allowed them to indicate aspects of the problem or situation that they want to prioritize, and the worker helped clients address those priorities first. The worker incorporated required activities and mandates later (Akbar, 2011), in a manner that left clients feeling empowered and supported in leading the direction of the intervention (O’Donnell et al., 2015). Clients also led the direction of the intervention when practitioners allowed them to update their preferences throughout the treatment stages (Österholm et al., 2015).

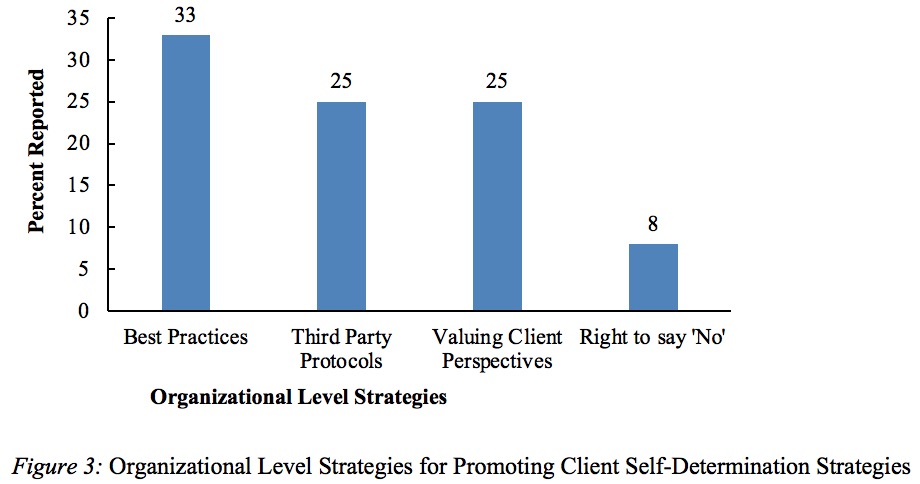

(b) Strategies at the Organizational Level. Figure 3 shows four strategies that were classified as occurring at the organizational level.

Strategies at the organizational level included safeguards on clients’ right to say “No” (Kvarnström et al., 2012), using third-party protocols, following best practices, and valuing client perspectives. Third-party arrangements involved consultations with relatives and other professionals to document the client’s wishes and preferences in instances where the identified client had significant limitations in their ability to fully participate in the self-determination process such as older adults with dementia or minors (Clark, 1998; Nordh & Nedlund, 2017; Österholm et al., 2015). Best practices reported in the articles were informed by models such as Self-Determination Theory’s (SDT) concept of client autonomy (Dennis, McCallion, & Ferretti, 2012; Lukens et al., 2013; Salazar, Noell, Cole, Haggerty & Roe, 2018), Shared Decision Making (SDM) reported by Lukens et al. (2013), and the Lundy Model (Kennan et al., 2019). Use of SDT principles allowed practitioners to operationalize client self-determination beyond what the client wants (Dennis et al., 2012) as practitioners let clients lead, demonstrated respect for clients’ decisions, supported clients in making their own decisions, and involved clients in program decision making and evaluation (Salazar et al., 2018). The strategies reported by Salazar et al. are consistent with Sheldon et al.’s (2008) recommendations for promoting client autonomy and giving consideration to clients’ interests and values in the decision making process. Another study that reported use of client autonomy was conducted by Lukens et al. (2013), who analyzed 435 vignettes completed by social workers; they found that 50% demonstrated support for client autonomy. However, practitioners were more likely to support client autonomy in vignettes with male clients, clients were not using substances, clients not living in group homes, and clients with major depression or bipolar disorder compared to those with schizophrenia (Lukens et al.).

One study out of the twelve studies focused on shared decision making. In this study, Lukens et al. (2013) found that 70% of the vignettes completed by social workers in the study sample demonstrated a willingness to engage clients in the shared decision making process, but its application also varied depending on client diagnosis with those experiencing schizophrenia less likely to be engaged in the SDM process compared to other diagnoses. The Lundy Model of Participation was reported in the article by Kennan et al. (2019), who reviewed 53 child welfare reports and open-ended responses from 370 practitioners and identified ways that children in care received space, voice, audience, and influence. Of direct importance to client self-determination is the concept of voice that was demonstrated by inviting children to participate in conferences in-person or through the use of forms and worksheets that the children completed prior to the meetings and gave to the practitioners for consideration during decision making.

The last strategy at the organizational level reported in the reviewed studies relates to agency commitment to valuing client perspectives that is demonstrated when mechanisms are developed and implemented agency wide to foster clients’ participation in the decisions making process and evaluation of whether or not their expectations were met (Kendall & Hugman, 2014; O’Donnell et al., 2015). Agencies can also express commitment to promoting client self-determination by fostering organizational cultures that are responsive to unique client needs and are flexible so that “anybody can kind of plug in” (Spitzmueller, 2014, p. 35).

Discussion and Implications for Practice

This systematic literature review sought to identify strategies that social workers use to promote client self-determination. The reviewed studies reported strategies that fall under two main categories, (1) worker-client level and (2) organizational level. Strategies for promoting client self-determination at the worker-client level included giving clients voice reported in 42% of the studies, educating clients (33%), giving clients opportunities to lead (25%), and giving clients choice (17%). Strategies at the organizational level ranged from best practices involving integration of components of Self-Determination Theory, the Lundy Model, or Shared Decision Making (reported by 33% of practitioners), valuing of client perspectives through evaluations or maintain responsive organizational environments (25%), using third party protocols (25%) and honoring clients’ right to turn down services (8%).

The first major finding is that all the reviewed studies described efforts to promote client self-determination that combined attention to clients’ uncoerced expression of their preferences and intentional actions by practitioners such as engaging third parties. Consequently, descriptions that combined various aspects of both worker-client and organizational level strategies were reported in the reviewed studies, suggesting the need to view client self-determination as best promoted on a continuum with enhancing clients’ individual capacities on one end to intentional manipulation of intervening variables in the broader environment that can facilitate or hinder clients’ self-determination on the other end. The identified strategies at the worker-client and organizational levels can be useful in developing frameworks that could guide procedures for ensuring client self-determination in social work practice.

The second major finding is that giving clients voice was the most common strategy, which is consistent with Gambrill’s (2013) recommendation that emphasized the importance of open dialogue between clients and practitioners to discuss client values, experiences and expectations in the client self-determination process. The social work assessment and diagnosis process remains an important point of entry into the client self-determination process (Kosko, 2013) as clients are encouraged to express their preferences and wishes. Social workers can use tailored agency forms and allowable media to facilitate continued expression of client voices regarding their care (Kennan et al., 2018).

The third major finding is that giving clients choice was the least common strategy, and this can be explained by the existence of factors that limit client choice and options such as funding requirements, health insurance policies, and program logistics (Rooney & Mirick, 2013; Wolfer et al., 2018). There is need for persistent advocacy and negotiation to expand options and opportunities to exercise choice for clients in spite of the restrictive contexts. This can be achieved by developing clear procedures at the agency level that outline how choice can be promoted and negotiated for clients. A useful tool that can be adopted to guide agency practices is person-centered planning, a process that involves consultation with a team of individuals and professionals in clients’ lives to support clients in articulating their preferences and sharing information that is used to formulate treatment goals and reviewed periodically to stay up to date with the clients’ preferences (American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person‐Centered Care et al., 2016).

Organizational policies can be pivotal in the promotion of client self-determination when they provide clear guidelines on the client self-determination process, best practices, and protocols for engaging third parties. Self-Determination Theory (SDT), Shared Decision Making (SDM), and the Lundy Model of Participation have concepts that can be integrated into agency procedures to strengthen client self-determination. The SDT concept of client autonomy lends itself into activities that facilitate the self-determination process as observed in the study by Salazar et al. (2018). Whereas adoption of SDM equips clients with tools that explain clinical information and options available to them to aid in reaching informed decisions about their care (Elwyn et al., 2010, p. 971), SDT’s concept of client autonomy ensures creation of a supportive environment where client perspectives and interests are considered. However, further research is needed to clarify integration of SDT, SDM, and the Lundy Model in efforts to enhance client self-determination.

Conclusion

Social workers have always championed the principle of client self-determination with varied implementation strategies to honor the unique needs of the diverse client groups. The reported systematic literature review has identified possible core elements, evolving best practices, and a multilevel framework for understanding and implementing client self-determination in social work practice. Key limitations of this research are that the studies reviewed in this project may not reflect the entire array of strategies used in social work practice. The client groups in the reviewed studies do not represent the entire spectrum of populations served by social workers. Furthermore, the reported strategies were not evaluated for their effectiveness. Future research can examine the effectiveness of the identified strategies and their utility with populations not reflected in the articles reviewed for this study. Even if tools for promoting client self-determination are available, there are specific instances where self-determination is limited, such as when there are competing values or client choices are illegal (Barsky, 2019). Other factors external to the organization, such as cultural expectations, may shape an individual’s participation in the self-determination process (Beckett & Maynard, 2005). Therefore, both agency administrators and practitioners play essential roles in collaborating and deliberating with their clients in the self-determination process.

References

Abbott, A. A. (1999). Measuring social work values: A cross-cultural challenge for global practice. International social work, 42(4), 455-470.

Akbar, G. L. (2011). Child welfare social work and the promotion of client self-determination. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Doctorate in Social Work (DSW) Dissertations. Paper 28. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/28

American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person‐Centered Care, Brummel‐Smith, K., Butler, D., Frieder, M., Gibbs, N., Henry, M., & Saliba, D. (2016). Person‐centered care: A definition and essential elements. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(1), 15-18.

Barsky, A. E. (2019). Ethics and values in social work: An integrated approach for a comprehensive curriculum (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Beal, S. J., Wingrove, T., Nause, K., Lipstein, E., Mathieu, S., & Greiner, M. V. (2019). The role of shared decision making in shaping intent to access services for adolescents in protective custody. Child Care in Practice, 25(1), 64-78.

Beckett, C., & Maynard, A. (2005). Values and ethics in social work: An introduction. London: Sage.

Clark, C. (1998). Self-determination and paternalism in community care: Practice and prospects. British Journal of Social Work, 28(3), 387-402.

Cummings, C. R., & Bentley, K. J. (2014). Contemporary health-related decision aids: Tools for social work practice. Social Work in Health Care, 53(8), 762-775.

Dennis, C. B., McCallion, P., & Ferretti, L. A. (2012). Understanding implementation of best practices for working with the older homeless through the lens of self-determination theory. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 55(4), 352-366.

Elwyn, G., Laitner, S., Coulter, A., Walker, E., Watson, P., & Thomson, R. (2010). Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ, 341, c5146.

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2014). The history of Self Determination Theory in psychology and management. In M. Gagné (Ed.). The Oxford handbook of work engagement, motivation, and self-determination theory (pp. 1-9). New York: Oxford University Press.

Gambrill, E. (2013). Social work practice: A critical thinker’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press.

Healy, K. (2000). Social work practices: Contemporary perspectives on change. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

Hepworth, D. H., Rooney, R. H., Rooney, G. D., Strom-Gottfried, K., & Larsen, J. (2010). Direct Social Work Practice: Theory and Skills (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Nelson Education.

Kendall, S., & Hugman, R. (2014). Power/knowledge and the ethics of involuntary treatment for anorexia nervosa in context: A social work contribution to the debate. The British Journal of Social Work, 46(3), 686-702.

Kennan, D., Brady, B., & Forkan, C. (2018). Supporting children’s participation in decision making: A systematic literature review exploring the effectiveness of participatory processes. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(7), 1985-2002.

Kennan, D., Brady, B., & Forkan, C. (2019). Space, voice, audience and influence: The Lundy Model of Participation (2007) in child welfare practice. Practice, 31(3), 205-218.

Kirst-Ashman, K. K., & Hull Jr., G. H. (2018). Generalist practice with organizations and communities (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Kosko, S. J. (2013) Agency vulnerability, participation, and the self-determination of indigenous peoples. Journal of Global Ethics, 9(3), 293-310.

Kvarnström, S., Hedberg, B., & Cedersund, E. (2013). The dual faces of service user participation: Implications for empowerment processes in interprofessional practice. Journal of Social Work, 13(3), 287-307.

Levin, L., Gewirtz, S., & Cribb, A. (2016). Shared decision making in Israeli social services: Social workers’ perspectives on policy making and implementation. British Journal of Social Work, 47(2), 507-523.

Lukens, J. M., Solomon, P., & Sorenson, S. B. (2013). Shared decision making for clients with mental illness: A randomized factorial survey. Research on Social Work Practice, 23(6), 694–705.

Lundy, L. (2007). Voice is not enough: Conceptualizing Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6)(6), 927-942.

McAlister, A. M., Lee, D. M., Ehlert, K. M., Kajfez, R. L., Faber, C. J., & Kennedy, M. S. (2017). Qualitative coding: An approach to assess inter-rater reliability. In ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Columbus, Ohio. https://peer. asee. org/28777.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman D.G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100.

National Association of Social Workers (NASW). (2017). Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

National Learning Consortium. (2013). Shared decision making. Retrieved online from https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/nlc_shared_decision_making_fact_sheet.pdf

Nordh, J., & Nedlund, A. (2017). To coordinate information in practice: Dilemmas and strategies in care management for citizens with dementia. Journal of Social Service Research, 43(3), 319-335.

O’Donnell, D., Treacy, M. P., Fealy, G., Lyons, I., & Lafferty, A. (2015). The case management approach to protecting older people from abuse and mistreatment: Lessons from the Irish experience. British Journal of Social Work, 45(5), 1451-1468.

Österholm, J. H., Larsson, A. T., & Olaison, A. (2015). Handling the dilemma of self-determination and dementia: A study of case managers’ discursive strategies in assessment meetings. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 58(6), 613-636.

Parkes, A. (2013). Children and international human rights law: The right of the child to be heard. New York: Routledge.

Peterson, K. J. (2012). Shared decision making in health care settings: A role for social work. Social Work in Health Care, 51(10), 894-908.

Pope, C., Mays, N., & Popay, J. (2007). Synthesising qualitative and quantitative health evidence: A guide to methods. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Rooney, R. H., & Mirick, R. G. (Eds.). (2018). Strategies for work with involuntary clients. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Publications.

Salazar, A. M., Noell, B., Cole, J. J., Haggerty, K. P., & Roe, S. (2018). Incorporating self‐determination into substance abuse prevention programming for youth transitioning from foster care to adulthood. Child & Family Social Work, 23(2), 281-288.

Sheldon, K. M., Williams, G., & Joiner, T. (2008). Self-determination theory in the clinic: Motivating physical and mental health. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Slade, M. (2017). Implementing shared decision making in routine mental health care. World psychiatry, 16(2), 146-153.

Spitzmueller, M. C. (2014). Shifting practices of recovery under community mental health reform: A street-level organizational ethnography. Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice, 13(1), 26-48.

Wheeler, B. Y., Lyle, A. D., Arnold, C. K., Williams, M. E., Imagawa, K. K., & Kim, M. A. (2016). Lifespan perspectives with developmental disabilities In E. M. P. Schott and E. L. Weiss (Eds.), Transformative social work practice (pp. 201-221). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Wolfer, T. A., Hodge, D. R., & Steele, J. (2018). Rethinking client self-determination in social work: A Christian perspective as a philosophical foundation for client choice. Social Work & Christianity, 45(2).