Archives > Volume 18 (2021) > Issue 1 > Item 07

DOI: 10.55521/10-018-107

Donna S. Wang, Ph.D.

Springfield College

dr.donnawang@gmail.com

Derek Tice-Brown, Ph.D.

Fordham University

adebrown@fordham.edu

Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics • Volume 18(1), Copyright 2021 by ASWB

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of ASWB.

Abstract

Contemplative practices such as yoga may have positive mental health outcomes on adolescents. This article reports on a qualitative study that examined how a mindful movement program based on yoga philosophy helped to affect cognitive processes that are compatible to social work values. Three focus groups and one individual interview were conducted for a total of 24 participants. Participants spoke of themes that indicated progress towards understanding the dignity and worth of people, the importance of human relationships, and the need for social justice. These social work values are then aligned with yoga philosophy.

Key words: contemplative practices, social work values and ethics, social justice, mindfulness, yoga

Contemplative practices are interventions that are increasingly more incorporated into social work practice for mental health and emotional, social, intellectual, and spiritual wellness. These practices are consistent with the social work values of self-determination and self-fulfillment, social and societal well-being, and social justice (Sherman & Siporin, 2008). Social workers use these practices to nurture introspection in their clients and themselves, and include activities such as mindfulness, meditation, storytelling, journaling, tai chi, and yoga (Wang, Perlman, & Temme, 2019). Evidence for such practices in social work dates as far back as 1997, when 15.4% of professional social workers surveyed reported that they use bodywork, such as yoga or tai chi, in practice, and 59.4% believed it to be appropriate (Jayarantre, Croxton, & Mattison, 1997).

A commonality of contemplative traditions is the unification of body and mind (Sherman & Siporin, 2008), which yoga is. Yoga is a form of mind-body medicine that provides a comprehensive system of self-development and transformation (Krucoff, 2013). Yoga, loosely translated from the Sanskrit yuj, means union. Yoga, although often seen as a primarily physical practice, also contains other elements of contemplative practices, such as mindfulness, meditation, and breathwork. The complex system is composed of eight limbs (Iyengar, 1966): yama (ethical principles), niyama (individuals’ rules of conduct), asana (physical postures), pranayama (breath control), pratyahara (control of the senses), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation) and samadhi (oneness). Many dimensions of yoga cultivate inner skills, such as self-inquiry and self-efficacy (Wang et al., 2019). However, just the physical practice has the same potential. For example, postures that are forward bending cultivate introspection, balance poses develop concentration, inversions energize the body (which may help alleviate depression), and meditation and relaxation help to combat anxiety.

Empirical support has documented the efficacy of contemplative practices, such as yoga, for emotional, social, intellectual, and spiritual wellness for recipients of social work services, including teens (Auty, Cope, & Liebling, 2017; Gockel, & Deng, 2019; Thomas, 2017). Past qualitative and quantitative studies suggest that yoga has benefited urban high school students (Felver, Butzer, Olson, Smith, & Khalsa, 2015; Ferreira-Vorkapic, Feitoza, Marchioro, Simões, Kozasa, & Telles, 2015; Frank, Kohler, Peal, & Bose, 2017; Noggle, Steiner, Minami, & Khalsa, 2012; Ramadoss, & Bose, 2010; Wang, & Higgins, 2016). One qualitative study among high schoolers found improved self-image and optimism, increased social cohesion with family and peers, and reductions in both stress levels and interest in the use of drugs and alcohol (Conboy, Noggle, Frey, et al., 2013). In another qualitative study, Wang and Hagins (2016) found that high school students participating in a yoga-based program reported increased self-regulation, mindfulness, self-esteem, physical conditioning, academic performance, and stress reduction. Frank, Bose and Schrobenhauser-Clonan (2014) found significant reductions in revenge motivation and reported hostility for at-risk youth participating in a yoga-based program. In another study conducted by Frank, et al. (2017), significant increases in student emotional regulation, positive thinking, and cognitive restructuring in response to stress were found in inner-city youths participating in a yoga-based program.

These outcomes that are a subsequent to participation in yoga-based interventions are important for today’s youth. It is imperative that we evaluate yoga theoretically through our discipline’s unique person-in-environment, empowerment, and strengths-based perspectives. Just as scholars from other disciplines (e.g., psychology, education) are establishing an empirical foundation of knowledge for yoga, social worker scholars also should contribute literature that incorporates our professional lenses. We are committed to formulating research questions and using research-informed practice that are congruent with our values and ethics. Social workers view and understand the human condition through a variety of perspectives, such as the micro/mezzo/macro levels, and use a strengths-based perspective. Additionally, our values and ethics are compatible with at least some aspects of yogic philosophy. For example, both yoga and social work value the dignity and worth of individuals and importance of human relationships. We are in a prime position to incorporate components of the philosophy and teaching of yoga in social work practice.

Although we are beginning to understand the benefits of yoga for adolescents, less is known about how yoga is externalized and may benefit relationships with others or how it translates into values and ethics associated with social work, such as social justice and empathy. Social workers have begun to incorporate elements of yogic philosophy and practice into their interventions, although with perhaps little understanding of its theoretical and practical integration. Wang and Tebb (2018) described how the philosophies of yoga and social work are compatible; however, much work remains to be done in order to demonstrate empirical evidence to support yoga’s applicability and appropriateness for the social work profession. Although there are articles and studies regarding mindfulness and meditation by social workers (e.g. McGarrigle & Walsh, 2011; Lee, Zaharlick, & Akers, 2011), a review of the literature found only nine articles regarding yoga in social work journals (Crews, Stolz-Newton, & Grant, 2018; Derezotes, 2000; Dylan, 2014; Gockel, & Deng, 2019; Jindani & Khalsa, 2015; Mensinga, 2011; Strauss & Northcut, 2014; Thomas, 2017; Warren & Chappell Deckert, 2019).

Although social workers are exposed to ways that social justice may manifest in the profession, less known are the deep philosophical roots of social justice and social action (Reamer, 2018). Aside from the political foundations, there are often personal philosophical underpinnings that contribute to social workers’ commitments to social justice. The ways in which individuals externalize the benefits of yoga to help bring compassion to one’s self and others and to promote social change and social justice need to be explored. Yogic philosophy is believed to be conducive to self-healing and transformation. One study showed that female survivors of sexual violence found yoga to be a beneficial way of (1) establishing better connections between themselves and the world around them, of (2) helping them move from positions of self-judgment to those of self-kindness, of (3) moving from isolation to common humanity, and of (4) moving from over-identification to mindfulness (Crews, Stolz-Newton, & Grant, 2018).

Thus, the purpose of this study was to further delineate the benefits of a yoga-based program and how these practices translate into social work principles and ethics of social justice. To do this, we analyzed empirical, qualitative evidence that was collected from high school students who participated in a Mindful Movement (MM) program and integrated it with social work values and ethics and yoga philosophy.

Background of the Mindful Movement Program

The MM program was offered to tenth graders who had never taken the program before. The program lasted for one semester (eighteen weeks, beginning in September and ending in January) and consisted of five sessions per week. Class periods were 56 minutes long, but after students changed and settled, the actual program time was about 45 minutes for four days per week and 30 minutes on the fifth. The program was intended to provide a balance of yogic elements, including pranayama (breathwork), asana (physical posturing), relaxation, positive visualization, and reflection (via journaling). Most sessions began with two to three minutes of active breath work (such as three-part breath, alternate nostril, breath counting) followed by at least twenty minutes of asana focusing on an awareness on the relationship with the body. There was a balance of vigorous (vinyasa flow) and restorative poses throughout the week. Sessions concluded with three to seven minutes of conscious relaxation, followed with either positive visualization or body scan relaxation. Journaling sessions included celebrating our gifts, telling our stories, and reflecting on growth throughout our lives.

The MM program was independently designed and implemented in an urban charter high school in Brooklyn, New York. The researchers were not involved in the design or implementation of the program. At the time of the study, the MM program was in its fourth year at the high school as an established part of the school’s curriculum. Because the program has had time to develop and because the school had received a great deal of positive feedback, school staff members sought out a more formal evaluation and contacted the lead researcher for program evaluation.

METHOD

School personnel were responsible for the recruitment of students to participate in the focus groups. All students assigned to the MM program were invited to participate, and the researchers obtained parental consent and assent for each student participant. The school staff sent informational letters and informed consent forms home to the parents to return. A total of 25 out of 50 parental consents were returned, resulting in a 50% response rate. These students were then gathered during their normal class time, at which time the researcher explained the procedures of the focus group, then obtained assents from the students. Students were audiotaped and the co-researcher also recorded notes. These procedures were approved by the authors’ Institutional Review Board at their home university.

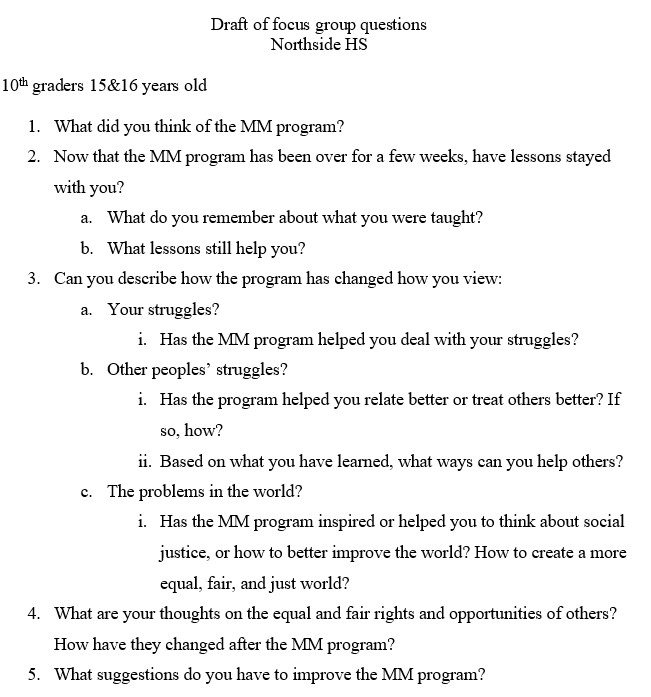

Three focus groups and one individual interview were held from January to March of 2018. The first focus group had seven students, the second had eleven, and the third had six students, for a total of 24 students. Each focus group lasted approximately 35-45 minutes. An individual interview was granted to one participant, who was unable to attend a focus group but who wanted to participate. The research team developed set of questions (see Appendix A) in advance to structure the focus groups; however, the researchers also allowed the participants to guide the discussion themselves. The recordings of the focus groups were transcribed by a graduate research assistant. Data were analyzed using the qualitative software analysis package Atlas.ti 8.

The data were first analyzed by two researchers independently to ensure validity. Informed by Miles and Huberman (1994), each researcher began the analysis with open coding, during which the researchers independently read each transcript and noted key descriptive words and phrases. The researchers’ next level of coding was interpretive, followed by pattern. Three key themes emerged that were related to the professional values of the field of social work: (1) the dignity and worth of the person, (2) the importance of human relationships, and (3) social justice.

RESULTS

Social Work Value: Dignity and worth of person

According to the NASW Code of Ethics, “social workers promote clients’ socially responsible self-determination. Social workers seek to enhance clients’ capacity and opportunity to change and to address their own needs. Social workers are cognizant of their dual responsibility to clients and to the broader society (NASW, 2017).” The participants spoke about learning or recognizing the dignity and worth of people, including themselves. Many students spoke about their own increased self-esteem, but also their increased compassion and empathy towards others, as well as broadened perspectives about other people’s actions and situations. Further, these broadened perspectives translated into decreased judgment toward others. The following are examples of quotes from participants that illustrate increased in self-value.

“As long as you’re happy with yourself and what you’re doing, how you’re doing it or whatever you’re doing, then that’s all that really matters.”

“My favorite lesson was self-value. Believing in yourself and being independent. We would do poses that you had to struggle and depend on yourself that you wouldn’t fall and to ground yourself.”

In addition to their own self-value, participants’ appreciation for other people also increased. As participants detailed how their self-esteem increased during the program, they also described their epiphanies regarding the interconnectedness of human beings, which deepened their understanding of the lived experiences of others. This also appeared to lead to increased compassion for others.

“The lesson was everyone’s connected in some way, we all have trouble but we can all get through it altogether, get through it together.”

“Sometimes you think they’re [referring to people who are homeless asking for money] going to buy drugs with it or something like that, so I’m not going to give you money if you’re just going to waste it, but then there’s some people that haven’t eaten and they want money to buy food for themselves and stuff. It makes you see stuff differently.”

“Some people lost their dads and sometimes I don’t appreciate my dad the way I should, you know? So you think you have it so bad but, look at the….yeah. And then, there’s this one girl, she has it really bad, but you see her smiling all the time. She has it so bad, but she doesn’t look at it negative, she looks at it positive. This shaped me to be a better person, all these things I went through, it made me better. She doesn’t like, oh my God, I went through this, I’m a failure blah blah, she sees it like, I’m ok. It made me better.”

“There was this other activity that I liked, and we taped a piece of paper on our backs and then we go around writing things you like about that person.”

Social Work Value: Importance of human relationships

Understanding the importance of human relationships is another value of the social work profession. Thus, social workers “seek to strengthen relationships among people in a purposeful effort to promote, restore, maintain, and enhance the well-being of individuals, families, social groups, organizations, and communities (NASW, 2017).” Yoga also stresses the importance of honorable relationships and stresses virtues such mindful listening, compassion, and working towards acceptance of a “difficult person (Krucoff, 2013).”

Improved relationships seemed to be a theme among these participants. Along with recognizing the worth of their peers and themselves, the participants also suggested that they internalized the importance of a greater good. A common theme that emerged from the focus groups was that yoga increased the quality of students’ personal relationships, including relationships with peers and family members. Participants also reported decreased sense of self-centeredness or duality with others. This adolescent phase in human development is largely focused on self-achievement and development; therefore, it may be helpful to have a perspective that decreases self-absorption and simultaneously increases self-awareness.

“Everybody else in the class has also been nicer, like genuine and caring for one another. So, I feel like it’s definitely had a positive impact on them.”

“It’s an open book with the people in the class. You just get to be yourself. You get to express yourself…. And she makes the class trust each other. I have really bad trust issues, but in that classroom, I felt I could trust people I never even spoke to.”

“It’s not my business, it’s not me being mistreated, it’s not any of my family. I said, I was really selfish. But now it’s, ‘Oh, that’s my friend that’s being treated like that.’ I feel like now, ‘You’re messing with her, you’re messing with me.’”

“I need to appreciate my mom. When I heard other people’s stories [about me] … Oh my God! I sound, I sound like a brat.”

“She’s made me not react to certain things. she’s made me not take out my emotions on everybody else. To center myself and fix myself and with the breathing, some poses, to just ground myself and not take out those emotions to people that don’t deserve for me to be mean to them.”

“I feel like it made me more understanding of other people. You see how we opened up in the room? They act a certain way and now you know why they acted that way.”

“A bunch of us got a clear understanding of why certain people act a certain way, and most of us, that day where we all like expressed our feelings or said what we were going through, we came much close with each other because now we knew what we go through, why we do the things we do.”

“Because there’s people out there that they’re going through situations and sometimes a negative approach will only make their day worse, so she told us to have empathy for everyone around us. That one I take home as well, because I don’t know if my mom had a rough day at work or my teachers, so that one is what I carry the most.”

Social Work Value: Social justice

The actions of helping others and taking responsibility for others in the above theme is progress towards social justice. Social workers pursue social change, particularly with and on behalf of vulnerable and oppressed individuals and groups of people (NASW, 2017). Students discussed learning the difference between action and reaction, and knowing when action is needed and not needed. Additionally, students showed increased awareness of inequality, compassion, and empathy.

“We all realized that not everybody is okay. Somebody’s always dealing with something. So, she always tells us, ‘If you see somebody in need, help them.’”

“I started to take a lot of things into consideration and then I just try to think of anything I can [to help]. I’m much more peaceful and calm now and I do help my peers calm down during certain things when they see other things.”

“It helped, the mindfulness, the conversations everyone had helped me. My own peers are going through some of this stuff, so let me help.”

“Don’t act on your feelings in the moment – think about it. Breathe first, and then react. Because the reaction you have automatically to the situation might be wrong.”

“Maybe you kind of pick and choose what you can do about something and you should be active or some things that you should just ignore and not give it any more thought.”

“I live on Long Island, so I often take three trains and a bus here and on a lot of the trains I see homeless people asking for change, or in the subway I’ll see them, or out on the streets. Before, I would just put my headphones on, put it on blast, so that I didn’t hear what they had to say or that I’d try to ignore them, so I didn’t have to give them money. My father is a boxer and my mother, she’s a nurse, so I come from where I have enough and if I have it, I can give it and I know that. But at that time I was just selfish, so now when I do see people on the train and I do see that they don’t have it, the little bit of money I can give, I give to them now. It makes me know if I do good, good will come back to me.”

“Recently I’ve been seeing it a lot and I’ve been helping the community and others.”

“Sometimes we buy a lot of food and we just throw it out, but like, there’s people that actually need the food or are hungry.”

“She (MM teacher) said his (her husband’s) neighborhood is very poor and she showed us pictures. It makes you appreciate what you have. Sometimes she goes there, and she does poses with those other kids, and it helps them, because they don’t get that, they don’t get that over there. So, she brings what she learns here over there. It makes me want to do a difference. In the school, sometimes we have drives where we all bring cans and they donate it, or we bring clothes that don’t fit us, and they donate it to other schools and stuff like that. And my mom, if I have clothes that don’t fit me, she packs it and she send it to DR (Dominican Republic) when she goes.”

DISCUSSION

These results support past findings that yoga practices help to promote positive outcomes in adolescents in many areas. Students spoke about how they learned how to relax, manage stress, and self-regulate through this program. These findings are similar to those of Wang and Hagins (2016), who also conducted focus groups with urban high school students about the effects of a yoga-based program. Another finding of our study, increased connections with and sense of responsibility for others, was also a main theme found by past researchers (Conboy et al., 2013). As theorized by Kohlberg (1976), this movement towards decreased self-centeredness is critical to moral development and to working for social justice.

Because these students were able to strengthen both their own relationships and connections to others, they were also able to see the need for social change and social action. This is suggestive of their understanding of relationships and of redistribution, in that there is some sense of equity and fairness. Some theories of justice suggest that justice is the calculation of who owes whom what and how much (Gasker & Fischer, 2014); however, there is also the concept of distributive justice, or allocation of resources (Reamer, 2018). Study participants recognized the need for distributive justice by understanding the need to reallocate resources to others who were in need. This might also be the beginning of the transformation from rational egoism, which is when a person is always acting in his or her self-interest, to altruism, which is doing an act for others in which one has no stake or claim (Pandya, 2017).

Although much is written about the social work value of social justice, less is articulated regarding the dignity and worth of persons or the importance of human relationships. Although these two values may seem self-explanatory, there is opportunity to unpack how individuals understand, value, and articulate these concepts on an individual basis and how they can be strengthened and transferred to others. Much research has done regarding how social workers understand and apply social work values, but transmitting those same values to and strengthening them within clients and society are also integral to creating the more just and equitable world for which we strive.

Yoga, although commercialized in the West and heavily marketed as a physical practice, is a “pragmatic science evolved over thousands of years dealing with the physical, moral, mental, and spiritual well-being of man as a whole (Iyengar, 1966, p. 13)”. A complete yoga practice is rooted in what can be considered to be moral living, which includes non-violence, truth, non-stealing, continence, non-coveting, purity, contentment, austerity, self-study, and devotion. It is generally accepted that the two main philosophical texts of yoga philosophy are the Bhagavad Gita (author unknown) and the Yoga Sutras by Patanjali. These two ancient texts have been translated into several languages and interpreted by many.

The Bhagavad Gita has been dated back to the fifth century BC (Mitchell, 2000). It is a poem depicting the main character, Arjuna, at war with his family. The Gita is a discourse between Arjuna and Krishna (God) about life, death, duty, nonattachment, the Self, love, spiritual practice, and the depths of reality (Mitchell, 2000). It is through this discourse that some of the ideas that are compatible to social work values can be found. For example:

“You must realize what action is, what wrong action and inaction are as well” (verse 4.17).

“Wise men regard all beings as equal: a learned priest, a cow, an elephant, a rat, or a filthy, rat-eating outcaste” (verse 5.18).

“They (wise men) can act impartially towards all being, since to them all beings are the same” (verse 5.19).

“This is true yoga: the unbinding of the bonds of sorrow…. Abandoning all desire born of his own selfish will, a man should learn to restrain this unruly sense with this mind” (verses 6.23-24).

“Even the heartless criminal, if he loves me with all his heart, will certainly grow into sainthood” (verse 9.30).

The above verses are examples of lessons that are applicable to social work, such as understanding reaction versus action, treating all as equal as means of achieving social justice, and valuing all people with a capacity to grow and change. They also reflect some of the concepts expressed (albeit articulated differently) by the student participants in this study.

The Yoga Sutras outline similar elements of nonattachment as the Bhagavad Gita, but also the complete practice of yoga. Book 2 verse 30 discusses the first limb of yoga, which are the five yamas. These outline how a person is to interact with one another and within the world. They are non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, continence, and non-greed (Satchidananda,, 1990). The second limb of yoga, the niyamas, are found in Book 2, verse 32 and are purity, contentment, accepting but not causing pain, study of spiritual books, and worship of God (Satchidananda, 1990). The niyamas provide guidance for a person’s own self-development. Many of both the yamas and niyamas are aligned with social work’s perspective on well-being and person-in-environment. This aspect of yogic philosophy, when incorporated into yoga practice, can have a strong impact on an individual’s well-being and functioning within the social environment. Practicing these ethical behaviors can improve our relationships with ourselves and with others (Krucoff, 2013). For example, the yamas of non-violence and non-stealing encourage acceptable behavior towards others. Self-study promotes a strengths-based perspective, as it requires that a person examines him or herself and commits to self-improvement, while also taking self-responsibility. Non-coveting and contentment demonstrate underlying principles of social justice, in that a person can strive towards not wanting what others have and being content with what one is and has, allowing for fairer and more equal distribution of resources.

CONCLUSION

Limitations for this study include the small, self-selected sample and possible multiple treatment interference, both of which are typical types of limitations among quantitative studies. The findings of this study suggest that progress towards social work values, such as the dignity and worth of individuals, the importance of human relationships, and social justice can be made through the practice of yoga. Social workers who may be daunted by social justice or who might shy away from more macro-oriented aspects of the profession may be encouraged by simple practices by individuals that may build impetus toward social change. Not everyone is interested in or capable of advocating for social change at a grand level through activities such as writing legislation or creating social change agencies, but they are able to engage in personal practices such as mindfulness and compassion that work towards that unified ideology.

References

Auty, K. M., Cope, A., Liebling, A. (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga and mindfulness meditation in prison: Effects on psychological well-being and behavioural functioning. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(6), 689-710.

Conboy, L. A., Noggle, J. J., Frey, J. L., Kudesia, R. S., & Khalsa, S. B. S. (2013).

Qualitative evaluation of a high school yoga program: feasibility and perceived benefits. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing, 9(3), 171-180.

Crews, D. A., Stolz-Newton, M., & Grant, N. S. (2016). The use of yoga to build self-compassion as a healing method for survivors of sexual violence. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 35(3), 139-156.

Derezotes, D. (2000). Evaluation of yoga and meditation trainings with adolescent sex offenders. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 17(2), 97-113.

Dylan, A. (2014). Noble Eightfold Path and Yoga (NEPY): A group for women experiencing substance use challenges. Social Work with Groups, 37(2), 142-157.

Felver, J., Butzer, B., Olson, K., Smith, I., Khalsa, S. (2015). Yoga in public school improves adolescent mood and affect. Contemporary School Psychologist, 19(3), 184-192.

Ferreira-Vorkapic, C., Feitoza, J. M., Marchioro, M., Simões, J., Kozasa, E., & Telles, S. (2015). Are there benefits from teaching yoga at schools? A systematic review of randomized control trials of yoga-based interventions. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2015.

Frank, J. L., Kohler, K., Peal, A., & Bose, B. (2017). Effectiveness of a School-Based Yoga program on adolescent mental health and school performance: Findings from a randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 8(3), 544-553.

Frank, J. L., Bose, B., & Schrobenhauser-Clonan, A. (2014). Effectiveness of a school-based yoga program on adolescent mental health, stress coping strategies, and attitudes toward violence: findings from a high-risk sample. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 30(1), 29-49.

Gasker, J. A., & Fischer, A. C. (2014). Toward a context-specific definition of social justice for social work: In search of overlapping consensus. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 11(1), 42-53.

Gockel, A., Deng, X. (2016). Mindfulness training as social work pedagogy: Exploring benefits, challenges, and issues for consideration in integrating mindfulness into social work education. Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 35(3), 222-244.

Iyengar, B. (1966). Light on Yoga. Schocken Books.

Jayaratne, S., Croxton, T., & Mattison, D. (1997). Social work professional standards: An exploratory study. Social Work, 42(2), 187-199.

Jindani, F., & Khalsa, G. F. S. (2015). A Journey to Embodied Healing: Yoga as a Treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 34(4), 394-413.

Kohlberg, L. (1976). Moral stages and moralization: The cognitive-developmental approach. In Lickona, T. (Ed.), Moral development and behavior. Theory, research, and social issues (p. 31-53). Holt.

Krucoff, C. (2013). Yoga sparks. New Harbinger Publications.

Lee, M. Y., Zaharlick, A., & Akers, D. (2011). Meditation and treatment of female trauma survivors of interpersonal abuses: Utilizing clients’ strengths. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 92(1), 41-49.

McGarrigle, T., & Walsh, C. A. (2011). Mindfulness, self-care, and wellness in social work: Effects of contemplative training. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 30(3), 212-233.

Mensinga, J. (2011). The feeling of being a social worker: Including yoga as an embodied practice in social work education. Social Work Education, 30(6), 650-662.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). An expanded sourcebook: Qualitative data analysis. Sage Publications, Inc.

Mitchell, S. (2000). Bhavagad Gita. A new translation. Three Rivers Press.

National Association of Social Workers (NASW). (2017). NASW Code of Ethics. NASW Press.

Noggle, J., Steiner, N. J., Minami, T., & Khalsa, S. (2012). Benefits of yoga for psychosocial well-being in a US high school curriculum: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 33(3), 193-201.

Pandya, S. P. (2017). Living Gurus, Their Ministries and Altruism as a Value: The Enterprise of Faith-Based Social Service. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 14(1), 5-20.

Ramadoss, R. and Bose, B. (2010). Transformative life skills: Pilot study of a yoga model for reduced stress and improving self-control in vulnerable youth. International Journal of Yoga Therapy, 1(1) 73–78.

Reamer, F. G. (2018). Pursuing Social Work’s Mission: The Philosophical Foundations of Social Justice. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 15(1), 34-42.

Satchidananda, S. (1990). The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Integral Yoga Publications.

Sherman, E., & Siporin, M. (2008). Contemplative theory and practice for social work. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 27(3), 259-274.

Strauss, R. J., & Northcut, T. B. (2014). Using yoga interventions to enhance clinical social work practices with young women with cancer. Clinical Social Work Journal, 42(3), 228-236.

Thomas, J. T. (2017). Brief mindfulness training in the social work practice classroom. Social Work Education: The International Journal, 36(1), 102-118.

Wang, D., & Hagins, M. (2016). Perceived benefits of yoga among urban school students: A qualitative analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2016. URL: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2016/8725654/

Wang, D. S., Pelman, A., & Temme, L. J. (2019). Utilizing contemplative practices in social work education. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thoughts, 39(1), 47-61.

Wang, D. & Tebb, S. (2018). Yoga and Social Work: The Shared Philosophies and Practices of Holism, Wellness and Empowerment. In Lee, M. (Ed.). Integrative Body Mind Spirit: An Empirically Based Approach to Assessment and Treatment, 2nd Ed. Oxford University Press.

Warren, S., & Chappell Deckert, J. (2019). Contemplative practices for self-care in the social work classroom. Social Work, 65(1), 11-20.

Appendix A