Archives > Volume 19 (2022) > Issue 1 > Item 08

DOI: 10.55521/10-019-108

Margo J. Heydt, Ed.D., LISW-S

Xavier University

heydt@xavier.edu

Timothy E. Severyn, MSW, MTS, MBA

Xavier University

severynte@xavier.edu

Author Note: Marie J. Giblin, Ph.D., now retired from the Department of Theology at Xavier University, was the original co-developer of this model with M. J. Heydt and was the ethics theologian who conceived of applying the Wesleyan Quadrilateral to an ethical decision-making process incorporating spirituality in the early 2000s. The authors thank her for continued support.

International Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics • Volume 19(1), Copyright 2022 by IFSW

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of IFSW.

Abstract

Social workers and other helping professionals act as moral agents within society when faced with ethical dilemmas. Over the last three decades, there has been a proliferation of ethical decision-making models available to practitioners that range from the rational, centered on objective step-by-step actions, to the reflective, focused on the character and outlook of the practitioner. Responding to calls for a more integrative approach to ethical decision-making grounded in the virtue of moral courage, this article introduces the Inclusive Wesleyan Quadrilateral Discernment Model (WQ Model). Drawing from a range of interprofessional literature, this model combines attributes of both rational and reflective models, with an emphasis on cultural humility and spiritual discernment. Unlike other integrative methods, the WQ Model applies a holistic bio-psycho-social-spiritual approach to understanding the practitioner as moral agent. Engaging the religious and spiritual dimensions of practitioners, this model centralizes each practitioner’s unique sources of moral knowledge and contextual diversity experiences through application of the Wesleyan Quadrilateral. With an emphasis on spiritual discernment, the WQ Model places the Wesleyan Quadrilateral in dialogue with the moral principles of bioethics for resolving ethical dilemmas and reducing moral distress.

Keywords: spirituality, diversity, ethical decision-making, interprofessional, moral agency

Introduction

The Inclusive Wesleyan Quadrilateral Discernment Model (WQ Model) is an evolving bio-psycho-social-spiritual holistic and comprehensive ethical decision-making model for practice professionals that integrates diversity awareness and spiritual discernment into the process of resolving complex ethical dilemmas within helping professions. Although this model emanates from the field of social work, it is intentionally interprofessional, grounded in literature from several professions and disciplines. As McAuliffe (2019) has reminded us, the World Health Organization in 2008 strongly urged a shift from teaching within traditional academic silos towards more collaborative engagement across disciplines in the best interests of patient care for individuals, families, and communities. McAuliffe (2019) specifically advocated for teaching interprofessional courses for practice professional students, stating that “Where IPE (Interprofessional Education) comes into its own is in those courses that set up simulated situations in which students from different disciplines work together in a deliberative and collaborative way to problem-solve a clinical case involving a patient” (p. 391). The classroom is exactly the context in which this model was developed, over a fifteen-year period of team teaching a course in which interdisciplinary groups apply the WQ Model to complex, practice-based cases involving culturally diverse and religious or spirituality oriented ethical dilemmas. This paper merely presents the model and does not focus on teaching; however, based on this teaching experience, we strongly support McAuliffe’s (2019) premise and suggest that increased interdisciplinary scholarship can only strengthen such a shift.

The discipline of professional ethics, as Reamer (2019) has summarized, emerged in the 1970s from roots in moral philosophy, eventually developing its own ethical theories and practice models applicable to a range of ethical dilemmas. Reamer (2019) also clearly identified one of the central ongoing struggles within the profession as the effort to balance concerns regarding the inclusion of marginalized populations’ unique experiences and perspectives with the need to uphold core values and best practice standards. The WQ Model addresses this question by providing a new process through which practice professionals decide who upholds what in which scenario, particularly when more and more diverse voices are included in the process of resolution.

Within the debate about process, identity, and standards, an aspect of the decision-making process that is gaining attention is the role of self-awareness of the decision-maker, the practitioner. In addition to seemingly more objective external sources of decision-making guidance from rationally focused theories and codes of ethics, the WQ Model emphasizes consideration of internal sources of influence through a process of self-reflection focused on spirituality and cultural humility. Building upon the bioethical foundations of applied ethics laid by Beauchamp and Childress (2013), the WQ Model is predicated upon the conviction that social workers, and most helping professionals, act as moral agents committed to engaging their whole bio-psycho-social-spiritual selves in the process of resolving ethical dilemmas.

For practitioners engaging their whole selves when examining ethical dilemmas, there is a need for timely self-awareness to help in comprehending the many internal as well as external factors at play. Increasingly recognized within most practice professions, cultural competence and cultural humility are essential aspects of engaging one’s whole self. Within both diversity discourse and contemporary dialogues about practitioners as moral agents, paying increased attention specifically to the roles of spirituality, religion, and spiritual discernment can be revealing and beneficial.

The WQ Model relies on Canda and Furman’s (2010) original holistic definitions of spirituality and religion as foundational, providing a comprehensive and inclusive conceptualization for the model’s emphasis on spiritual discernment. Canda and Furman (2010) have stated;

I conceptualize spirituality as the gestalt of the total process of human life and development, encompassing biological, mental, social, and spiritual aspects…. The spiritual relates to the person’s search for a sense of meaning and morally fulfilling relationship between oneself, other people, the encompassing universe, and the ontological ground of existence. (p. 66)

Canda and Furman (2010) have differentiated this primarily internal human experience from the more external manifestations of religion in the following way: “religion involves the patterns of spiritual beliefs and practices formed in social institutions and traditions that are maintained in a community over time” (p. 66). Spiritual discernment in the context of the WQ Model does not reference or favor any particular religious practice. Spiritual discernment refers to the more general act of reaching a decision only after reflecting, meditating, or praying upon the unique intersections of diversity characteristics and sources of moral knowledge that together inform how practitioners, as moral agents, understand and resolve ethical dilemmas.

Regarding diversity and inclusiveness, there is general acknowledgement that the U.S. is projected to become a majority-minority nation for the first time over the next few decades. Relevant to that shift, in 2015, the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) updated their Standards and Indicators for Cultural Competence in Social Work Practice document, which states:

Standard 1. Ethics and Values

Social workers shall function in accordance with the values, ethics, and standards of the NASW (2008) Code of Ethics. Cultural competence requires self-awareness, cultural humility, and the commitment to understanding and embracing culture as central to effective practice. (p. 4)

In addition to race, the NASW Standards and Indicators for Cultural Competence in Social Work Practice (2015) further identified the following categories of social identity and diversity characteristics:

Diversity, more than race and ethnicity, includes the sociocultural experiences of people inclusive of, but not limited to, national origin, color, social class, religious and spiritual beliefs, immigration status, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, age, marital status, and physical or mental disabilities. (p. 9)

Newer ethical decision-making models will need to be explicitly grounded in cultural humility and responsive to the changing demographics of the populations served without sinking into relativism. Already complicated ethical dilemmas become even more so when considering the multiple worldviews of all parties involved, including those of practitioners. Several steps of the WQ Model include clearly identifying social identity variables and their influences.

The WQ Model builds upon the Transcultural Integrative Model of ethical decision-making from the field of counseling. Garcia et al. (2008) have emphasized that “The need to be inclusive of cultural variables extends to the development of ethical decision-making models, which, to date, have not incorporated such factors systematically” (p. 21). Due to the WQ Model’s emphasis on diversity and spiritual discernment, applying the Comparison Chart of Selected Ethical Decision-Making Models from Garcia et al. (2003) helps identify where the WQ Model fits into an increasing array of approaches to ethical decision-making in practice. Along with the Transcultural Integrative Model, the WQ Model is situated in the Integrative category of blending a rational approach with virtue ethics. Referring to their own Transcultural Model, Garcia et al. (2003) have stated, “Because it combines rational and virtue ethics, users of this model focus on both the dilemma and the character of the counselor while considering contextual factors” (p. 271).

The most unique aspect of this new integrative model, however, involves using the Wesleyan Quadrilateral (an 18th-century decision-making framework in which scripture, tradition, reason, and experience intersect) to apply an emphasis on spiritual discernment to ethical decision-making. Informed by virtue ethics, the WQ Model presumes that the moral character and moral courage of the reflective decision-maker sheds light upon the pursuit of rational, right (correct) action by the practitioner. Towards these ends, this model places a significant emphasis upon self-reflection throughout the process of ethical decision-making, incorporating the concept and language of moral agency as described by Strom-Gottfried (2019) in the field of social work. Referring to practice as moral agency, Strom-Gottfried (2019) has provided a detailed description of moral distress and moral courage as aspects of self-awareness that help a professional identify additional components of ethical dilemmas as well as find the fortitude to choose and then act upon their resolutions. This review of the development and key components of the WQ Model requires considerable background information. It begins with literature regarding ethical dilemma decision-making models in interprofessional practice. This is followed by an explanation of moral courage terminology, the Wesleyan Quadrilateral sources of moral knowledge, the role of rational moral principles, and finally presenting the WQ Model.

Literature Review

In existing literature, the role of practitioner self-awareness in ethical decision-making has been often debated by ethicists from various practice fields. As Reamer (2019) pointed out, “Like philosophers, social workers disagree about the objectivity of ethical principles” (p. 15). In placing the emphasis on the process rather than the practitioner, currently dominant ethical decision-making models in social work barely reference self-awareness or reflection.

In social work, two models have dominated the field: those of and Dolgoff et al. (2012) and Reamer (2013). While the two have significant differences, both are grounded in a scientific/rational approach to decision-making that assumes a good process in itself will lead to the best outcome. Such an approach dismisses virtue ethics as lacking in objectivity and favors a more mechanistic approach grounded in deontology, consequentialism, or both. In fact, Dolgoff et al. (2012) have stated that;

Traditional models of ethical decision making offer some guidance as to what to do by providing principles and tools by which professional social workers may make ethical choices. In this book we place emphasis on rational, scientific, systematic, and less ambiguous decision-making processes instead of on the personal characteristics of the decision maker. (p. 64)

Both Reamer’s (2013) and Dolgoff et al.’s (2012) models fit in the rational category of Garcia et al.’s (2003) ethical decision-making models comparison chart.

While not ignoring the importance of process and scientific rationalism, the WQ Model is grounded in a central tenet of virtue ethics: the practitioner matters as much as the process. Each actor in an ethical dilemma, whether client or practitioner, is contextually bound, with unique experiences, both individually and communally, as part of diverse communities with intersecting social identities and worldviews. As such, a bio-psycho-social-spiritual awareness of who the practitioner is becomes as important as the process they use to resolve an ethical dilemma. The WQ Model calls for both spiritual and cultural self-awareness by including multiple opportunities for objective factor identification as well as subjective reflection. Since the character of the actor becomes as important as the goodness of the action, applying the WQ Model relies on the incorporation of virtue ethics into decision-making, in alignment with ethics scholarship from multiple disciplines.

From psychology, Kitchener (1984) has addressed the lack of integrating self-awareness into ethical decision-making models. In the counseling literature, Stadler (1986) put forth a justified reasoning process in which practitioners are described as moral agents in comparison to ordinary citizens due to the roles they play in their clients’ lives. Stadler (1986) stated:

As moral agents with special responsibilities, we recognize the fallacy of thinking ourselves to be neutral, unbiased observers of the lives that pass before us…. We conscientiously endeavor to reduce the impact of our values on our clients by clarifying our own value expectations and by allowing clients to consider their own values and freely chosen goals. (p.4)

In the social work literature, Mattison (2000) noted that ethical decision-making should rely on the profession’s code of ethics, but also emphasized the importance of self-awareness. She stated:

Yet the code does not specify which values or principles the social worker should consider primary in cases of competing interests…. Although systematic guides for resolving ethical dilemmas offer social workers a logical approach to the decision-making process, to some extent, the use of discretionary judgments is inevitable. (p. 203)

Nodding towards the influence of diversity issues, Mattison (2000) also noted that the value system and preferences of the decision maker affect every step of assessment as well as final outcomes.

Integrating Mattison’s (2000) reflective approach and Garcia et al.’s (2008) transcultural one with the dominant rational process models of Reamer (2013) and Dolgoff et al. (2012), McAuliffe and Chenoweth (2008) introduced an Inclusive Model of Ethical Decision-Making. This model is one of the earliest efforts within the field of social work towards such integration. McAuliffe and Chenoweth (2008) have observed:

From our work with practitioners and students, we identified a need for a model that was inclusive of both important concepts on which practice is based, and systematic steps to create a more comprehensive and robust model suited to many practice situations. The model also needed to be inclusive of the most important values that form the foundation of social work and human services. (p. 41)

More recently in social work, Barsky (2019a) has likewise challenged the strict rationalism of the dominant models through his “Framework for Managing Ethical Dilemmas,” a step-by-step method that includes both a rational process for decision-making and a complementary emphasis on the practitioner as decision-maker, including a call to “reflect on one’s own values, virtues, attitudes, beliefs, motivations, emotions, capacities, challenges, and social contexts” (p. 272). Elsewhere, Barsky (2019b) has proposed integrating Narrative Ethics more fully into social work, emphasizing cultural humility and starting where the client is through active listening. Barsky advocates that there may be more than a single story of what is right in any given dilemma.

Speaking from an Islamic perspective, Eltaiba (2019) further integrated these cultural and reflective elements, with a reminder that;

Social workers bring to their practice their family structure, gender, experience, values, and cultural and religious affiliation—all of which would invite a range of interpretations of ethics for ethical decision making… the emphasis on critical thinking and reflection, when dealing with ethical dilemmas and making ethical decisions, is congruent with social work ethicality. (p. 290)

Eltaiba’s (2019) work supports the bio-psycho-social-spiritual inclusive approach of McAuliffe and Chenoweth (2008), providing an Islamic case study to specifically illustrate how religious cultural sensitivity and reflection can be included in ethical decision making.

Synthesizing the themes from this interdisciplinary literature review, we argue for effectively reintroducing virtue ethics into ethical decision-making for practice professionals. By combining a concern for practitioner self-awareness with a rational process for resolving dilemmas, these theorists lay the foundation for the emergence of new integrative models, including this WQ Model.

In broadening the discussion beyond rational scientific analysis to include self-awareness and reflection regarding diversity and moral agency, the WQ Model proposes that a methodical approach to spiritual discernment can be of value. Few models specifically incorporating spiritual discernment to assist in ethical decision-making exist. Most of the models in this interdisciplinary review do not specifically emphasize spirituality when they advocate incorporating self-awareness. In contrast, the WQ Model intentionally introduces methodical spiritual discernment as a central aspect of self-awareness and moral agency. Like Beauchamp and Childress (2013) in bioethics as well as Stadler (1986) in counseling, Strom-Gottfried (2019) in social work has referred to helping professional practitioners as moral agents. Along with Kitchener (1984) from psychology, Stadler (1986) explained that “any time we think or act on what we believe to be right or wrong, good or bad, we are concerned with the moral dimension of life” (p. 2). Strom-Gottfried (2019) put forward moral courage as the virtue that moves individuals to act ethically even when their principles or values are short circuited by various barriers and they risk disapproval, isolation, or termination. She has pointed out that such barriers can be external and/or internal and that moral courage “is built and sustained through self-awareness about the personal barriers to action” (p. 68).

“Moral residue” as explained by Strom-Gottfried (2019) refers to the cumulative effects of moral distress, a concept first identified in the nursing field of the practice literature by ethicist Andrew Jameton in the 1980s. Wilkinson later expanded upon the concept in the nursing literature (Burkhardt & Nathaniel, 2014). In defining moral distress, Wilkinson (1987) described “the psychological disequilibrium and negative feeling state experienced when a person makes a moral decision but does not follow through by performing the moral behavior indicated by that decision” (p. 16).

While Strom-Gottfried (2019) has focused more heavily on external constraints to a determined course of action, such as agency policy, she also refers to the possibility of psychological trauma experienced by the thwarted practitioner struggling with internal conflict when faced with an ethical dilemma. In describing moral distress as manifesting itself in both physical and emotional symptoms, Strom-Gottfried has provided helpful terminology. The virtue of moral resilience can overcome moral distress and bolster moral courage: “While moral distress arises from and evokes feelings of powerlessness, moral resilience suggests flipping the narrative to focus on solutions and possibilities” (Strom-Gottfried, 2019, p. 69). Because practitioners act as moral agents in society, moral cowardice and disengagement need to be minimized in every helping profession by maximizing moral courage and resilience through increased recognition of moral distress internally and externally.

Strom-Gottfried (2019) proposed that a “fresh discourse” about moral distress factors and how to address them can contribute to the moral courage of practitioners. Eltaiba (2019) likewise suggested the need for “future dialogue” surrounding the role of spiritual reflection and cultural sensitivity in shaping moral agents’ responses, noting “there is no training in how to link these thoughts and this spirituality to ethical issues and ethical decision-making” (p. 296).

The WQ Model begins to meet both of these author’s concerns through an emphasis on practitioners’ bio-psycho-social-spiritual self-awareness of themselves as moral agents who are equipped to manage increasingly complex ethical dilemmas. More specifically, the WQ Model pursues increased practitioner self-awareness through spiritual discernment which requires attunement to the spiritual dimensions of self. These efforts are undertaken only after the practitioner has entered a space of reflection, meditation, or prayer.

Wesleyan Quadrilateral

The Wesleyan Quadrilateral was identified in the twentieth century by Albert Outler, an academic and ordained Methodist Elder. When reviewing the writings of John Wesley, the English founder of the Methodist denomination in the 1700’s, Outler (1985) noted Wesley’s use of four sources of moral knowledge throughout his sermons:

- scripture

- tradition (beliefs and practices passed from generation to generation)

- reason (science)

- experience (both individual and communal)

Christian scholars continue to use this method of organizing information and evaluating the factors involved in any dilemma to develop contemporary theology and ethics (Thorsen, 2005; Salzman and Lawler, 2018).

The WQ Model opens up the Wesleyan Quadrilateral to use by practitioners, regardless of religious status or faith-based background, by encouraging them to interpret the four sources of moral knowledge broadly, as described in the sections below. The model encourages practitioners to engage in methodical spiritual discernment, reflecting upon their own unique sources of moral knowledge from their social identity characteristics as well as their religious or spiritual foundations. By making this examination explicit, the WQ Model encourages practitioners to ask themselves:

- What sources of moral knowledge do I bring to this dilemma?

- How does each act as resource for resolution, broadening my understanding of the dilemma?

- How do these sources act as barriers to resolution, creating biases within my worldview that need to be objectively negotiated?

Scripture

Scripture can be understood as those authoritative textual sources, often believed to have come from divine origins or to have been divinely inspired, that have shaped and may continue to serve as a resource for a particular practitioner. These include the Christian Bible, the Jewish Torah, the Muslim Qur’an, the Buddhist Tripitaka, The Vedas from Hinduism, and many other texts from any number of spiritual traditions. While the sacred passages a practitioner selects may not deal immediately with a specific issue, such as genetic testing or in vitro fertilization, they may still illuminate the dilemma by highlighting particular values or themes. In exploring scripture, a practitioner might begin by asking:

- What light does scripture shed on the ethical dilemma, and how does that content inform my understanding of it?

- Are the passages I have selected consistent with the major themes of the sacred text or are the passages being proof-texted, cherry-picked, or used out of context?

- What were the cultural perspectives and intended messages of the writers of the passages being examined?

- What additional messages am I hearing today from my own vantage point?

In some cases, the scriptural prescriptions might be quite clear as in the Christian Ten Commandments or Jewish Kosher rules. In others, general narrative themes such as “love your neighbor” or “provide aid to orphans, widows, and strangers” may be more relevant to a particular case. And some religious prescriptions, such as stoning adulterers, are rarely implemented in contemporary societies.

Tradition

Religious tradition can be understood as an evolving set of shared beliefs and spiritual practices that have been transmitted by a community over time. Tradition is often formed from an array of diverse, even competing, foundations, including the examples of historical figures such as theologians or Christian saints, religious teachings such as in the Muslim Hadith or Jewish Midrash, or practices of particular religious communities such as the Jesuits or the Amish. Like scripture, traditions may have shaped and may continue to inform how a particular practitioner acts as a moral agent when faced with an ethical dilemma. In exploring tradition, a practitioner might ask:

- What light does this tradition have to shed upon the ethical dilemma and how does it inform my understanding of it?

- Can one say that a certain view has had significant support in the tradition over time, or are there alternative, countervailing traditions, such as in the cases of polygamy/plural marriage, child brides, or wearing a burkha?

- Is the tradition internally diverse (such as Reform vs. Orthodox Jew or traditional vs. progressive Catholics), with a variety of resources to draw upon?

- How much value is being placed on doing things a certain way because it has always been done that way and by whom is it valued?

- Are there other voices within the tradition that have not frequently been heard, such as those of women, people of color, or LGBTQ+ individuals?

Answering such questions can help practitioners understand some of the cultural factors at play within their traditions, opening space to consider potential discrepancies or tensions within the tradition – such as Christian support for slavery in the U.S. South or determining whether or not women should be allowed to drive in Saudi Arabia.

Reason

Reason can be understood broadly as the sciences, from the physical sciences to the social sciences, which play a major role in shaping how contemporary practitioners understand and resolve ethical dilemmas. In exploring reason, a practitioner might ask the following:

- What light does reason have to shed upon the ethical dilemma and my understanding of it?

- Is the issue being thought through in ways that are coherent and credible?

- Is there scientific inquiry or research that provides important information from the fields of social work, psychology, sociology, and medicine?

- How can questioning, probing, and attempting to use the best insights of contemporary science deepen spiritual beliefs and make them more meaningful today?

- In what ways is science playing a role in the dilemma that conflicts with spiritual or religious beliefs?

Exploring reason can help the practitioner to identify both best practices supported by empirical data—such as vaccination to prevent diseases like COVID-19—and practices that are not evidence-based, such as conversion therapy for persons who identify as LGBTQ+.

Experience

Experience can be understood as the broad constellation of individual and communal realities not captured in the previous three sources of moral knowledge. Experience centrally includes diversity concerns that may have been marginalized or erased from mainstream historical accounts, such as in cases of intimate partner violence, workplace harassment, police brutality against people of color, or the violence of the Holocaust. Practitioners, like all human beings, have been shaped by their experiences and worldviews, relying upon them consciously or unconsciously as they resolve ethical dilemmas. In exploring experience as a source of moral knowledge, a practitioner might ask the following:

- What light does my personal or collective experience shed upon the ethical dilemma and my understanding of it?

- What have been my personal experiences tied to this dilemma, and how might that both support and bias or limit my understanding of the issues at hand?

- What is the collective historical experience of this issue?

- Is the historical religious view consistent with contemporary experience regarding issues and events?

- Whose contemporary experience(s) have been centralized? Whose have been marginalized?

Considering these questions encourages cultural humility and helps a practitioner contextualize both themselves and the dilemma, understanding it historically from multiple perspectives and diverse worldviews.

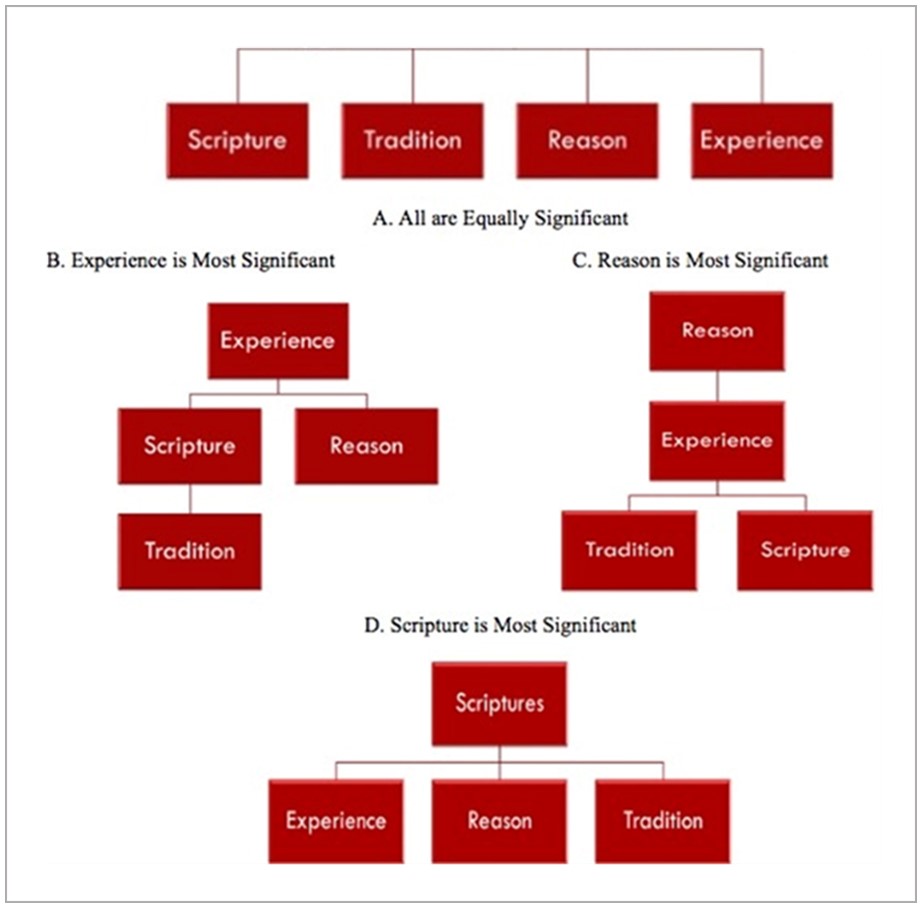

According to Thorsen (2005), the Wesleyan Quadrilateral has been traditionally employed by Christians for religious purposes to explain how God is active in reality, calling forth right action. From Thorsen’s perspective, Wesley intended for scripture to exert the strongest influence among the four sources. While he encouraged interplay with the other three sources, scripture would ultimately outweigh them (sola scriptura) if there was a conflict during ethical decision-making. Theologians Salzman and Lawler (2018) provide a solid theological grounding for de-prioritizing scripture, placing each of these sources upon equal grounding, through what they call perspectivism. This refers to examining how moral agents engage in the “Selection, Interpretation, Prioritization, and Integration (or SIPI) of these sources from a virtuous perspective” (p. 93). Salzman and Lawler contend that different SIPI configurations are required for different ethical dilemmas and that there is no one size fits all configuration. This flexibility provides a way to see how different practitioners may arrive at different yet equally valid conclusions, based on their unique SIPI configurations of the four sources in a justified reasoning process, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Analyzing ethical dilemmas by considering one’s SIPI constellation of these four sources of moral knowledge—scripture, tradition, reason, and experience—grounds the practitioner as moral agent in a methodology of spiritual discernment, helping one better understand the foundations of one’s own ethical perspective, its strengths and limitations, and the critiques it faces. But recourse to the four sources is not a panacea. A Christian fundamentalist may only superficially consider tradition, reason and experience, evaluating them as inferior to the word of God in the Bible (See Figure 1, Model D). An agnostic or atheist may disregard scripture and tradition entirely, deciding these do not influence their decision-making, despite the penetration of many religious beliefs and customs into the culture at large, such as the dollar bill stating “In God We Trust” (See Figure 1, Model B and Model C). Still, applying the Wesleyan Quadrilateral can help practitioners weigh the roles of these four sources in their analysis of a dilemma, each applying their own unique configurations, unique to the dilemma and unique to the practitioner solving it.

Engaging the WQ Model encourages practitioners in their roles as moral agents in society by helping them understand the spiritual contexts from which they are acting and making decisions. While the WQ Model asks for more conscious deliberation of factors contributing to a complete and justified reasoning process, it also has the potential to sort which of these factors contribute most to moral courage and resilience as a moral agent. Since these four sources collectively inform each practitioner’s context and character, shaping the virtues that they bring to the dilemma, all four necessarily shape practitioner responses and eventual outcomes. The WQ Model brings to the forefront a more complete examination of conscious and unconscious competing values, virtues, and ethical claims.

Moral Principles

Considering the self as a moral agent within the context of an ethical dilemma, Beauchamp and Childress (2013), have contended that there is “a rough, although imperfect, correspondence between some virtues and moral principles” (p. 381). Rational moral principles can be explored concretely through specification, weighing, and balancing just like the four sources of moral knowledge of the Wesleyan Quadrilateral through Salzman and Lawler’s (2018) SIPI approach (Beauchamp & Childress, 2013). As originally introduced by contemporary philosopher Rawls (1971), lexical ordering of one moral principle over another in practice would depend on the case, the client, and the practitioner. When an ethical dilemma arises involving competing moral principles and/or sources of moral knowledge, spiritual discernment can facilitate rank ordering.

Beauchamp and Childress (2013) proposed four core moral principles:

- nonmaleficence (derived from the virtue of nonmalevolence)

- beneficence (derived from the virtue of benevolence)

- autonomy (derived from the virtue of respectfulness for autonomy)

- justice (derived from the virtue of justice)

For helping profession practitioners, the WQ Model adds a fifth to the standard list of four moral principles:

- veracity (derived from the virtue of honesty)

Before further explanation of the WQ Model, each of the moral principles is briefly reviewed below, as understanding them plays an important role in the model’s application.

Nonmaleficence: do no harm

Primarily a passive principle or negative injunction, nonmaleficence requires refraining from harmful acts, whether intentional or as a consequence of doing good, for example, such as refraining from engaging in dual relationships with clients or from practicing while impaired.

Beneficence: do good and prevent harm

As an active principle or positive injunction, beneficence requires actions that do good and intercede when harm can be prevented, such as preventing impaired colleagues from practicing or reporting suspected child maltreatment.

Autonomy: self-determination

This principle promotes self-governance, wherein a person is accorded the right to determine their own destiny even if these actions might bring them harm, such as in cases of assisted suicide or clients’ refusing medical treatment. Culturally, this principle is weighed considerably differently in Western vs. Eastern oriented societies.

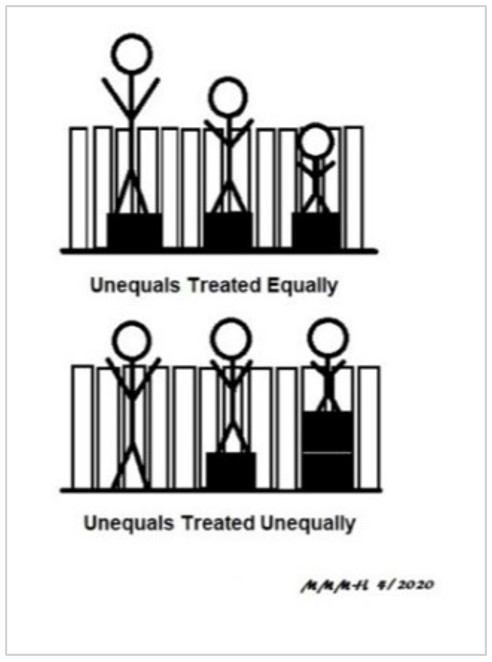

Justice: be fair

This principle requires fair, equitable, and appropriate treatment with equals treated equally and unequal treated unequally, as illustrated in Figure 2. For instance, consider the Special Olympics or how students with Down’s syndrome receive specialized education for math and science but are mainstreamed for physical education or music in schools.

Veracity: be honest

In helping professions, in which communication and developing relationships are essential, truthfulness would seem to be foundational. And yet, that is not and has not always been the case. Conventions of practice have certainly changed over time regarding who gets to know what and when about an adoption. Or consider when a family is in a serious car crash; to promote the health of a survivor, when should the patient be told that the rest of the family perished?

In dialogue with the Wesleyan Quadrilateral, these moral principles provide a way to integrate virtue ethics with rational analysis. By providing moral agents with concrete concepts that can be weighed and ranked through spiritual discernment, practitioners are better equipped to evaluate ethical dilemmas and arrive at directional decisions that both reduce moral distress and determine right action.

Inclusive Wesleyan Quadrilateral Discernment Model

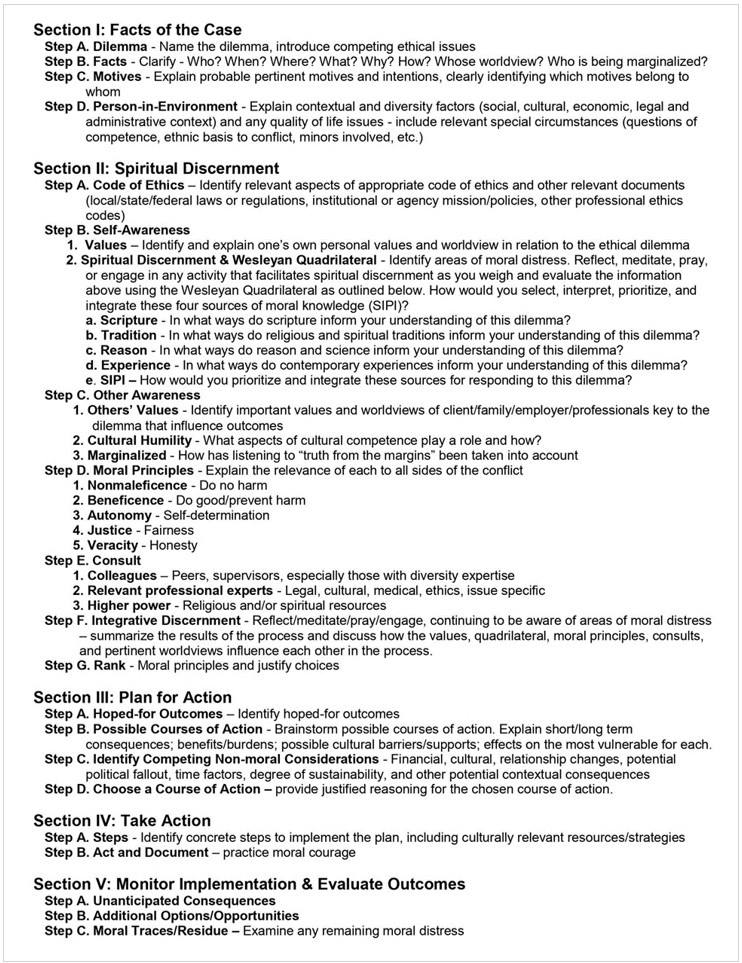

As a holistic bio-psycho-social-spiritual approach, the WQ Model has five main sections with multiple sub-sections or steps within each. The following sections examine application of each step, as outlined in Figure 3 (see previous page).

WQ Model, section I: Facts of the case

In Section I, Step A begins like most ethical decision-making models, with naming the dilemma and identifying the competing ethical issues or claims. In Step B, the goal is establishing the facts of the case. Answering as many of the fact-setting questions as apply lays the foundation for analysis. This includes the usual who/what/when/where as well as identifying pertinent worldviews. These facts should be verifiable. In contrast, Step C involves explaining probable motives and to whom they belong. Although some guesswork may be involved here, intentions can also be fairly clear—possibly financial, power, relationship building, healing, revenge, or righting a wrong. Step D ends the first section with a review of contextual factors and special circumstances. Pertinent diversity characteristics should be identified here as well as administrative, legal, and quality of life matters. Including as much information as possible here often times is clarifying in and of itself and may result in the revelation of a heretofore unidentified resolution to the dilemma.

WQ Model, section II: Spiritual discernment

Section II is the most substantive and unique aspect of this model, with seven major steps, including a focus on awareness of self and others. Several forms and levels of consultation and spiritual discernment are key. Step A begins with consulting pertinent professional codes of ethics for guidance, ensuring that a sufficient answer is not to be found in an appropriate code before advancing any further. Codes from other professions can be helpful as well, especially in situations involving interprofessional teams. This is also where other clear answers might be found in searching for legal or administrative rules. If no immediately clear direction for a decision is found, Step B, self-awareness, will guide the practitioner in evaluating what personal values and worldviews are playing a role in the dilemma or creating moral distress. The Wesleyan Quadrilateral’s four sources of moral knowledge are selected, interpreted, prioritized, and integrated (SIPI), contributing to increased self-awareness regarding the roles of religion, spirituality, and diversity in shaping, and potentially biasing, the practitioner’s understanding of the dilemma. Practitioners are asked to engage in activity that encourages spiritual discernment, such as meditation or prayer. This focus on self-awareness is followed by examining “other awareness” in Step C, identifying the worldviews, values, and biases of the others involved to the best of one’s ability, as well as aspects of diversity that may be playing a role. Practitioners are asked to identify how listening to “truth from the margins” has been taken into account.

Step D of Section II involves applying the five moral principles and identifying the relevance of each to this dilemma. This is followed in Step E by consultation with colleagues and professional experts with relevant knowledge that might influence the outcome. For instance, beyond clinical consults, a case involving a teenager who enjoyed explosives might warrant that a fire marshal be consulted. Step F asks for an integrative spiritual reflection of Steps B through E, discerning how the values, Quadrilateral, moral principles, and consulted experts influence each other and address the moral distress involved. This includes again engaging in reflection through meditation and/or prayer, similar to Step B but now including the additional information gleaned from completing the steps in between. Finally, in Step G of Section II, the practitioner ranks the principles, makes a choice, and finds justification for it: why this choice rather than that choice? This, however, is only a choice of direction and not one of action.

WQ Model, section III: Plan for action

It is common to want to move straight into action once a directional decision has been made. Usually, however, there is more than one way to follow through with a chosen direction. Section III tasks the practitioner with exploring options before acting. Both Step A, identifying hoped-for outcomes, and Step B, brainstorming the benefits and burdens of possible courses of action, reduce the “blinder effect” that can follow making a directional decision. A dilemma indicates two or more options that conflict but each option may have degrees of more or less favorable resolution. Discerning “favorable to whom” is an important part of a diversity-conscious benefits and burdens analysis. Identifying non-moral considerations in Step C that were not key in the conflict of the dilemma can be helpful as well. Will there be political ramifications? Is one choice more sustainable over time than another? Is the best choice unavailable to the client due to resources or geography? Section III ends with Step D: choosing a course of action and summarizing the justified reasoning for the choice.

WQ Model, section IV: Take action

In Section IV, the action plan is designed, with goals, objectives, tasks, and a timeline comprising Step A. Finally, the practitioner musters the moral courage to act and does so in Step B. Step B also includes documenting the action.

WQ Model, section V: Monitor and evaluate

Section V covers the ongoing implementation and assessment of the action plan, including measuring and evaluating the outcomes. Did the plan, as enacted, accomplish the goal? In Step A, the practitioner identifies any unanticipated consequences. Additional options or opportunities that presented themselves are described in Step B. And finally, Step C checks for moral residues or traces. That means going back to the original source(s) of moral distress, that tug that was the result of the conflicting or competing aspects of the dilemma. Does it feel resolved? What moral residue lingers that may still need attention?

Conclusion

This evolving model has been designed for both educational and practical settings. Although it has not been empirically tested on a specific population yet, the authors have found it very useful over many years of encouraging students to reflect on their characters as moral agents as well as learn skills of self-reflection, cultural humility, ethical analysis, and decision-making in an interprofessional classroom setting. Feedback indicates that the WQ Model provides a useful tool for assisting students and practitioners to identify and respond to numerous aspects of ethical dilemmas through a unique justified reasoning process. Understandably, real-world dilemmas often involve time constraints that limit a thorough application of this comprehensive model. Models that explicitly incorporate diversity concerns into a bio-psycho-social-spiritual approach are needed. Because spirituality and religion are aspects of diversity as well as foundations from which many practitioners and their clients operate, both warrant increased recognition in ethical decision-making. Controversial and often polarizing stances regarding the separation of church and state in the helping professions and practice settings point to the need for methodical ways to intentionally and explicitly consider how spirituality and religion interface in ethical practice.

The Inclusive Wesleyan Quadrilateral Discernment Model is grounded in the understanding that social workers and other helping profession practitioners are called to act as moral agents, often in interprofessional settings, when faced with complex ethical dilemmas. It builds upon an interprofessional body of literature with a foundation in virtue ethics that emphasizes the importance of holistic self-awareness and reflection for the practitioner with ethical concerns and dilemmas. The underlying assumption of this model is that, in the process of justified reasoning, it is important to make the unconscious conscious. Applying the Wesleyan Quadrilateral to the decision-making process provides a method for identifying and consciously monitoring elements of one’s subjective social identity and the spiritual or religious biases that may be influencing decision-making processes. Importantly, using the model, constructs, and processes advanced in this article can help practitioners find and maintain a sense of spiritual discernment and cultural humility, while reducing moral distress and increasing moral courage. Unique among ethical decision-making models, the WQ Model provides a holistic comprehensive reflective tool that empowers practitioners in their actions as moral agents with colleagues in interprofessional settings.

References

Barsky, A. E. (2019a). Ethics and values in social work: An integrated approach for a comprehensive curriculum (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Barsky, A. E. (2019b). Narrative ethics in social work practice. In S. M. Marson & R. E. McKinney (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of social work ethics and values (pp. 51–57). Routledge.

Beauchamp, T. L. & Childress, J. F. (2013). Principles of biomedical ethics (7th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Burkhardt, M. A. & Nathaniel, A. K. (2014). Ethics & issues in contemporary nursing (4th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Canda, E. R. & Furman, L. D. (2010). Spiritual diversity in social work practice: The heart of helping (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Dolgoff, R., Harrington D., & Loewenberg, F. M. (2012). Ethical decisions for social work practice (9th ed.). Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning.

Eltaiba, N. (2019). An ethical decision-making model: An Islamic perspective. In S. M. Marson & R. E. McKinney (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of social work ethics and values (pp. 289–296). Routledge.

Garcia, J. G., Cartwright, B., Winston, S. M., & Borzuchowska, B. (2003). A Transcultural Integrative Model for ethical decision-making in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 81(3), 268–277.

Garcia, J. G., McGuire-Kuletz, M, Froelich, R., & Pooja, D (2008). Testing a transcultural model of ethical decision-making with rehabilitation counselors. The Journal of Rehabilitation, 74(3), 21–26.

Jameton, A. (1984). Nursing practice: The ethical issues. Prentice Hall.

Kitchener, K. S. (1984). Intuition, critical evaluation and ethical principles: The foundation for ethical decisions in counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 12(3), 43–55.

Mattison, M. (2000). Ethical decision-making: The person in the process. Social Work, 45(3), 201–212.

McAuliffe, D. (2019). Interprofessional ethics: Working in the cross-disciplinary moral and practice space. In S. M. Marson & R. E. McKinney (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of social work ethics and values (pp. 388–395). Routledge.

McAuliffe, D. & Chenoweth, L. (2008). Leave no stone unturned: The inclusive model of ethical decision making. Ethics and Social Welfare, 2(1), 38–49.

National Association of Social Workers. (2015). Standards and indicators for cultural competence in social work practice. NASW Press. https://www.socialworkers.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=PonPTDEBrn4%3D&portalid=0

Outler, A. C. (1985). The Wesleyan Quadrilateral in Wesley. Wesleyan Theological Journal, 20(1), 7–18.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Harvard University Press.

Reamer, F. G. (2013). Social work values and ethics (4th ed.). Columbia University Press.

Reamer, F. G. (2019). Ethical theories and social work practice. In S. M. Marson & R. E. McKinney (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of social work ethics and values (pp. 15–21). Routledge.

Salzman, T.A. & Lawler, M.G. (2018). Virtue and theological ethics: Toward a renewed ethical method. Orbis Books.

Stadler, H. A. (1986). Making hard choices: Clarifying controversial ethical issues. Counseling and Human Development, 19(1) 1–10.

Strom-Gottfried, K. (2019). Ethical action in challenging times. In S. M. Marson & R. E. McKinney (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of social work ethics and values (pp. 65–72).Routledge.

Thorsen, D. (2005). The Wesleyan quadrilateral: A model of evangelical theology. Emeth Press.

Wilkinson, J. M. (1987). Moral distress in nursing practice: Experience and effect. Nursing Ethics, 14(3), 344–349.