Archives > Volume 22 (2025) > Issue 1 > Item 05

DOI: 10.55521/10-022-105

Jay Sweifach, DSW, MSW, LCSW

Yeshiva University, Wurzweiler School of Social Work

Orli Sweifach

Yeshiva University, Wurzweiler School of Social Work

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of IFSW.

Abstract

This article presents findings from a study designed to explore the perceptions of social work faculty about out of work behavior (OWB) and other activities within the private-life realm. A focus is placed on the intersection between OWB and social work education. Major research questions asked respondents to reflect on (1) whether private-life behaviors change as a result of social work education; (2) the extent to which social workers are expected (and students should be taught) to maintain high moral standards in their private lives. Implications of study findings are discussed, highlighting the potential for schools of social work to implement best educational practices that relate to personal life responsibilities. An internet-based survey was used to reach a broad spectrum of respondents. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Keywords:

Social Work Ethics, Private-life behavior, social work education

Introduction

Social work is commonly acknowledged as a profession grounded in core values and ethical principles (Barsky, 2019; Noble & King, 1981; Osmo & Landau, 2003; Reamer, 2018; Sweifach, 2011). These principles are outlined in the International Federation of Social Workers [IFSW] Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles (2018), emphasizing the unique commitment of the social work profession to social justice, social change, and the promotion of general welfare. Social workers are expected to engage in social and political action, combat exploitation and discrimination, and uphold a host of core values that reflect a deep concern for individuals and society (Reamer, 2018). Scholars contend that social work is one of the most value-based professions, with practitioners adhering to core values due to their concern for humanity (Chechak, 2015; Reamer, 2018). A mindset predisposed toward creating a better world necessitates internal desire, personal commitment, and accountability. For many, this predilection begins long before social work training. It makes sense that many social workers would likely act on these values even if they had not pursued a career in social work.

Through their codes of ethics and other regulations, professions often articulate expectations that extend to the private-life behaviors of their members, expecting that certain values and behaviors are maintained. The concept of ‘outside-work behavior’ (OWB) describes actions taken by employees outside their professional roles that include both private and public behaviors (Althoff, 2000). This perspective is seen in virtue ethics, which suggests that moral character ought to remain consistent across both professional and personal domains of practice (Cornwell & Higgins, 2019). The practical rationale for this perspective is clear; when professionals act in ways that are anathema to the values of the profession, its integrity becomes suspect.

The topic of OWB is commonplace in the news. The private-life behaviors of musicians, actors, politicians, and other public figures are frequently on display and often judged. In today’s cancel-culture world, such public scrutiny can have detrimental fallout, serving as a reminder that private-life behavior is something to consider because the general public is watching. Beyond public figures, the private-life behaviors of professionals are also highlighted by the media: for example, teachers involved in indiscretions with students or viral videos showing police officers engaged in racist behavior. These types of activities attract considerable public attention.

This study explores the perspectives of social work faculty members regarding OWB, examining the extent to which faculty members believe that social workers ought to be guided by professional standards in their personal lives. A specific focus is placed on how these views are considered within the context of social work education.

Clarification of terms

In the literature, several terms are used to describe the behavior of employees outside of working hours, such as ‘off-duty behavior,’ ‘private-time behavior,’ and ‘non-working hours behavior.’ OWB, however, appears to be the scientific term most often used. Moral behavior is defined as a code of conduct that corresponds with society’s expectations of good character in professionals and as a representation of core values and norms, such as virtue, honesty, respect, and integrity, which help maintain public trust. A moral exemplar is an individual whose behavior consistently reflects moral excellence, serving as a behavioral role model for others and the broader community (Morgenroth et al., 2015; Yin & Li, 2023).

Background

Some professions more than others, articulate clear expectations regarding OWB, specifying that members are to act in their private lives with integrity, honesty, and trustworthiness (see, for example, General Osteopathic Council [GOsC], 2019; International Association of Chiefs of Police [IACP], 2008; National Association of School Psychologists [NASP], 2020). Personal behavior and conduct are expected to be principled, as poor private-life behavior is seen as potentially eroding public trust and jeopardizing the dignity of the profession (Garner & O’Sullivan, 2020; Halabuza, 2014).

Although some commentators advocate for personal autonomy and argue against imposing standards on private behavior (Clark, 2006; Lippke, 1989; Olivier, 2006), this does not tend to be a majority view. Many professional organizations require that their members uphold high standards of conduct both in and outside of the workplace. These standards include honesty, legality, and respect for others (GOsC, 2019; IACP, 2008; NASP, 2020). The National Association of School Psychologists (NASP, 2020, p. 40), for example, articulates that their members should maintain a high standard of good character and conduct in their private lives because they serve as role models for children. The General Osteopathic Council (GOsC, 2019) in the United Kingdom stipulates that members are to “uphold the reputation of the profession at all times through [one’s] conduct in and out of the workplace” (p. 19). The International Law Enforcement Code of Ethics (IACP, 2008) mandates that all sworn police officers keep their “private life unsullied as an example to all.” In both professional and personal life, “be honest in thought and deed” and “be exemplary in obeying the laws of the land” (p. 111).

Expectations of good private-life moral conduct extend to social work as well, with practitioners expected to act according to these standards in both their professional and personal lives (Adusumalli & Jainer, 2020; Banks, 2016; Levy, 1974; Miller, 2022). IFSW’s Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles (2018) emphasizes that ethical responsibilities extend beyond the workplace, encouraging social workers to advocate for human rights and social justice, celebrate diversity, work toward equal access to resources, and promote a culture of peace and nonviolence. Although the current United States NASW Code of Ethics (2017/2021) avoids specificity about private-life conduct, the 1979 iteration of the Code of Ethics included the principle of propriety, specifying that “the social worker should maintain high standards of personal conduct in the capacity or identity of social worker” (National Association of Social Workers [NASW], Code of Ethics, 1979). Other social work codes, such as those from the British Association of Social Workers (2002) and the Scottish Social Services Council (2003), specifically state that social workers must uphold standards of conduct both inside and outside work.

Social work education plays a critical role in shaping the professional identity of students (Liu et al., 2022; Wiles, 2013). Commentators suggest that students are engaged in a process of cultivating a sense of ‘being’ a social worker in order to ‘become’ one (Wiles, 2013). When one ‘becomes’ a social worker, this extends into the private-life realm. Students become inculcated into this process early on in both classroom and practicum learning, with expectations to act with integrity and professionalism. MSW and BSW school catalogs emphasize the many sides of personal and professional comportment, such as punctuality, dependability, and commitment to diversity. Many schools also note a responsibility to adhere to high standards of ethical behavior in both personal interactions and online activity, avoid the use of illegal substances, and refrain from becoming romantically involved with clients. These school/professional expectations are very much connected to the personal realm, endeavoring to teach students that professional practice and personal behavior are linked. An implicit message is conveyed about the importance of upholding certain personal values and behaviors so as not to cast aspersions on the profession or school. This socialization process is all part of ‘becoming.’ Wiles (2013) suggested that the ways in which students think and behave in their personal lives are significantly influenced by their social work education. ‘Becoming’ a social worker involves the internalization of a unique ‘moral core’ of the profession (Bisman, 2004; Butler-Warke & Bolger, 2021; McBeath & Webb, 2002), which calls for consistency between private-life behaviors and professional principles (Knapp & Vandecreek, 2006).

For social workers, whom some view as defenders of social morality (Glasser, 1984), consistency in representing virtuous character traits in both personal and professional life is crucial. Although it is clear that the profession places a substantive emphasis on ethical behavior, which does extend into private life, questions remain about whether social workers themselves agree with these expectations.

Literature

Research on OWB spans several disciplines, frequently addressing the topic of private-life misconduct as it relates to professional reputation and moral integrity. Scholars have produced a wide range of work in disciplines such as law, medicine, and education, emphasizing the moral obligations of professionals beyond their work environment (Althoff, 2000; Gagnon, 2015; Kaptein, 2019; Lister, 2022; Meadows, 1993; Ross et al., 2013; Sawicki, 2009). Substance use, domestic violence, and discriminatory conduct are examples of behaviors that do not go unnoticed, particularly within the context of ‘cancel culture,’ which has emerged as a societal process for holding individuals accountable for perceived transgressions. In practice, being ‘canceled’ may involve public shaming or ostracizing, loss of employment, or reputational damage following controversial behavior or perceived moral/ethical transgressions. (Norris, 2021). The behaviors that result in individuals being ‘canceled’ have been studied theoretically and empirically in the literature. For instance, the private lives of teachers (DiCenso, 2005; Maxwell, 2018), police (Abel, 2022; Lamboo, 2010), clergy (Hargrove, 2023), healthcare professionals (Thompson et al., 2008; Marshal et al., 2021), educators (Griffin & Lake, 2012; Zinskie & Griffin, 2023), and law professionals (Menkel-Meadow, 2001; Rhode & Woolley, 2011), have all been the subject of scholarly work on the moral realm of OWB, emphasizing the importance of professionals being mindful of their private-life behavior.

In one of the most comprehensive recent works on OWB, Kaptein (2019) offers a thorough discussion and overview of OWB, including its many definitions and iterations, interdisciplinary applications, and how scholars interpret and understand the concept today. Kaptein (2019) also highlights the range of interdisciplinary research around OWB, including its application in professional sports, healthcare, law enforcement, politics, and other sectors.

A growing area of OWB research focuses on online activity, particularly social media, where private posts can quickly become public and impact professional standing (Byrne, 2019; Cook & Kuhn, 2020; Drude & Messer-Engel, 2020; Marshal et al., 2021; Mauldin, 2024; Sarmurzin, et al., 2025). A significant proportion of recent literature in this area pertains to the perceptions of students and the concept of e-professionalism, exploring the issues and risks associated with inadequate personal oversight of social media and other online activities (Hussain et al., 2021; Kamarudin et al., 2022; Nasri et al., 2023). Much of this literature concludes that, while individuals have a right to privacy, they must also be mindful that their behavior is subject to public scrutiny and that poor private-life judgment can lead to significant professional consequences.

It is clear from much of the literature that principles guiding OWB, whether professional or organizational, are very subjective, though broad guidelines around areas such as confidentiality and integrity are generally consistent across disciplines. More specific guidelines, however, are quite varied; for example, regarding private-life social media use, some agencies might require that employees avoid posting content that could be seen as discriminatory, offensive, or unprofessional. In general, there is some expectation by both agencies and professional regulatory bodies that professionals will uphold good character in their private lives, which includes behavior that promotes moral norms of virtue and integrity.

A significant debate within the recent literature centers on whether employers/regulatory bodies have the right to regulate employee behavior outside of working hours and, if so, to what extent (Kaptein, 2019; Lister, 2022; Sperdin & Situm, 2024). Some scholars argue that private-life misconduct should have professional repercussions only when directly related to specific work-related situations. Some in the same camp argue that protecting private life is a “considerable and humane public good” (Whittle & Cooper, 2009, p. 98), advocating for allowing professionals some moral slack in their private lives (Menkel-Meadow, 2001). Others advocate “the good of accountability” (Allen, 2003, p. 1387) in order to maintain public trust (Bryan-Brown & Dracup, 2003; Milton, 2014; Staud & Kearney, 2019). What stands out in the literature is the lack of consensus over whether individuals should face termination for off-duty misconduct (Drouin et al., 2015) and the need for policy and guidance surrounding private-life conduct (Maxwell, 2018).

Despite the growing body of literature examining OWB in professions such as law, medicine, and education, the social work literature has primarily focused on ethical misconduct related to direct practice, such as boundary issues, dual relationships, and confidentiality (Boland-Prom et al., 2015; Congress, 2001; Pugh, 2007; Reamer, 2003, 2013; 2018; 2023). While these behaviors sometimes occur outside of working hours, they are directly tied to professional duties. The scholarship in this area, which is relatively extensive, largely focuses on malpractice claims and ethics complaints against social workers (see, for example, Barsky et al., 2021; Boland-Prom et al., 2015; Reamer, 1995; Strom-Gottfried, 2003; 2014). Conversely, aside from a few studies on private-life social media use (see, for example, Duncan-Daston et al., 2013; Fang et al., 2014; Mukherjee & Clark, 2012), and Reamer’s (2017; 2019) work on evolving ethical standards, which does speak to the need for caution in personal online activity, off-duty behavior unrelated to direct-practice remains underexamined in the social work literature.

Some research in the social work literature highlights the debate over regulatory oversight of private life, particularly in the United Kingdom, following the development of the General Social Care Council (2002), which developed a code of conduct to regulate and discipline social workers (see for example, Clark, 2006; Furness, 2015; McLaughlin, 2007; Wiles, 2013). Studies have raised concerns about regulatory intrusion into private life, focusing on moral character and suitability for the profession. Wiles (2013), for example, examines social work students’ perceptions of private-life behavior, suggesting that while social workers certainly have a right to a private life, there is also a responsibility to ensure that off-duty behavior adheres to professional norms. McLaughlin (2007), questions whether the state has the right to regulate the private-life conduct of social workers, and Furness (2015) examines the ethical implications of such oversight.

The social work literature also explores private life as it relates to the character of students’ and suitability for the profession (Currer, 2009; Holmström, 2014; Tam & Coleman, 2009). Banks (2016) writes about the character trait of integrity, suggesting, like other commentators (Musschenga, 2002; Oakley & Cocking, 2001), that social workers possess “a disposition to act with integrity in the variety of situations encountered in their professional lives, and according to many theorists and most codes of ethics, also in their personal lives” (p. 11).

An expansion of social work research in these and other areas of private-life conduct could provide a clearer understanding of the responsibilities that social workers have regarding private-life behavior, such as providing more explicit professional guidelines for outside-work conduct, clarifying the extent to which private-life conduct ought to be regulated, defining what constitutes moral turpitude, and elucidating the issues and risks associated with poor private-life conduct.

Methodology

Research Design and Objectives

This study employed a descriptive, exploratory design to investigate the following:

- The views held by social work faculty regarding the private-life behavior of social workers.

- The extent to which private-life behaviors become modified as a result of social work education.

- The extent to which social workers and social work students should be expected to maintain high moral standards in their private lives.

Participants and Sampling Procedure

A purposive, non-random sampling approach was used to select 15 universities in the United States, offering MSW and BSW programs. The selection of schools was based on a review of accredited institutions listed by the Council on Social Work Education [CSWE]. The schools were chosen from four distinct geographic regions (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West) to represent a mix of large and small schools, as well as public and private universities. This purposive approach was used to maximize variability in institutional and faculty contexts, enhancing the generalizability of findings. Faculty members from the selected universities were contacted via email, with contact information obtained from publicly available faculty directories on university websites. The email invitation provided information detailing the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, and the confidentiality of their responses.

A total of 83 survey responses were initially collected. However, 14 responses were excluded from the analysis due to incomplete data or non-responsiveness to key survey items, reducing the final usable sample to 69 faculty members. The exclusion of these responses did not significantly affect the demographic composition of the final sample, but it is important to note that the analyses were conducted with a sample size of 69, which limits generalizability.

Survey Instrument

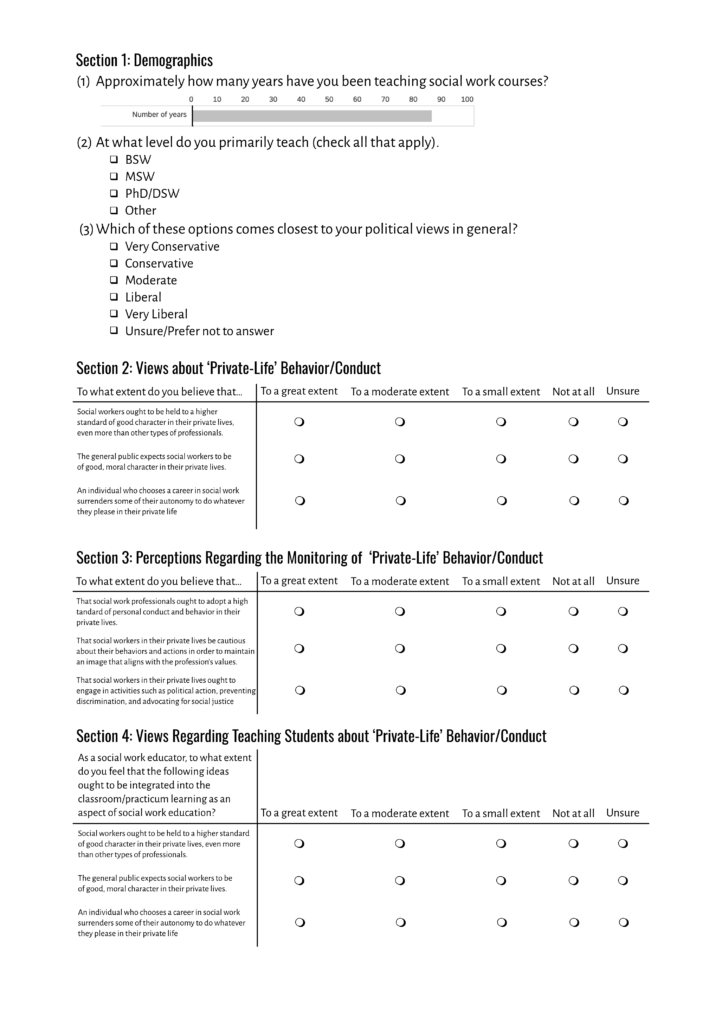

The survey instrument featured questions on OWB perceptions, practices, behaviors, and sociodemographic factors. The survey included questions about both personal beliefs regarding OWB and whether OWB-oriented content ought to be integrated into classroom/practicum learning. Also asked were questions about whether private-life behavior ought to be externally monitored in some way (Appendix 1 includes a sample of survey questions). Alongside multiple-choice questions (with response options of ‘to a great extent,’ ‘to a moderate extent,’ ‘to a small extent,’ ‘not at all,’ and ‘unsure,’) it included open-ended questions that allowed respondents to elaborate on answers to Likert scale items. The 53-item survey was pilot-tested with a small, representative sample of social work faculty to assess face validity and reliability. Based on feedback from the pilot test, minor revisions were made to improve clarity and ensure that all items adequately captured the constructs under study. Reliability analysis indicated that the instrument demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, yielding a Cronbach’s alpha of .87.

Collection Procedure & Informed Consent

Data were collected through an online survey administered to social work faculty from July 1st through August 31st, 2024. A reminder email was sent to participants one week and again three weeks after the initial invitation and the survey closed on September 30th, 2024. Before beginning the survey, participants were informed of the study’s purpose, confidentiality measures, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequence. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection, and all procedures adhered to ethical guidelines. Data were collected and stored in a secure, password-protected database to maintain confidentiality. Responses were anonymized prior to analysis to ensure that no personal identifiers were included in the dataset.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 29.0 to examine the relationships between various variables and test the study’s underlying assumptions. Descriptive statistics were first computed to summarize the characteristics of the sample. Specifically, means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages were calculated for categorical variables to provide a general overview of the data. Continuous variables were examined for distributional properties, and where applicable, t-tests and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used to assess differences across groups.

Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were computed to explore relationships between continuous variables. This provided insight into the strength and directionality of associations between key variables and provided a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness between personal views about OWB, professional commitments, and opinions regarding the teaching of OWB principles to students.

In order to ensure the validity of findings, assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were tested prior to conducting parametric tests, and where necessary, non-parametric alternatives were considered. All statistical tests were conducted at a significance level of p ≤ .05 to determine whether observed patterns were statistically significant.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

The final sample comprised 69 full-time social work faculty members. Faculty teaching responsibilities were diverse: (45.3%) of respondents exclusively taught Master of Social Work (MSW) courses, with the remaining respondents instructing in a variety of social work courses, including Bachelor of Social Work (BSW), MSW, Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), and Doctor of Social Work (DSW). Respondents had a wide range of teaching experience, with the number of years of teaching experience spanning from 1 to 54 years (M=14.52 years), which indicates a moderate to highly experienced group of faculty.

Political orientation was diverse, reflecting a range of perspectives. Specifically, 1.6% of respondents identified as very conservative, while 6.2% identified as conservative. A larger portion of the sample, 17.2%, identified as moderate. The majority identified as liberal (37.5%), and very liberal (31.2%), showing a strong inclination toward liberal ideologies within the group. This ratio is consistent with other data (see, for example, Stoeffler et al., 2021) on the social work labor force, reflecting a strong leaning toward liberal and progressive ideologies. A small proportion (6.2%) of respondents were unsure or preferred not to answer regarding their political orientation.

Geographic Location

Respondents, all from the United States, provided their state of residence, which was coded into the 10 Federal regions used for census purposes. These regions were then recoded into four broader geographic areas: Northeast, South, Midwest, and West. This categorization allowed for an examination of potential regional differences in attitudes toward OWB and social work education. While specific regional distributions are provided in Table 1, the general geographic breakdown reflects the diversity of the sample in terms of location. The inclusion of faculty from various regions helped to promote a more representative sample rather than being biased by the views of faculty from a particular region.

| Recoded Region | Sample Representation |

| Region 1 = Northeast | 64.52 % (n=40) |

| Region 2 = Midwest | 19.35 % (n=12) |

| Region 3 = South | 8.06 % (n=5) |

| Region 4 = West | 8.06 % (n=5) |

Views about the OWB of social workers

A majority, 62.5% (n=40), believe that social workers should be held to higher moral standards compared to other professionals. Additionally, 68.7 % (n=44) believe that social workers should serve as moral exemplars for society. With regard to views about societal perceptions, almost three-quarters (73.4 %, n=47) of respondents believe that the general public expects social workers to maintain elevated private-life conduct. A substantial proportion (68.7 %, n=44) suggests that participating in private-life behaviors, such as making offensive racial jokes or displaying prejudiced attitudes, can potentially have a negative impact on society’s view of the profession. Opinions were more mixed about whether a social worker’s moral character is a public matter, with just over half (53.9 %) either disagreeing or only somewhat agreeing that it is.

Oversight of OWB

Regarding external monitoring, just under 40 % (39.1 %, n=25) believe that agencies should have some say in how social workers act outside of working hours. Nearly three-quarters (70.3 %, n=45) argue against state licensing board oversight of OWB. Just over one-third (36 %, n=23) believe that schools of social work ought to conduct some level of social media screening of applicants to assess whether they demonstrate a moral character that aligns with the profession.

Teaching about Private-life Behavior to Students

An index was created to assess perceptions of whether social work education affects changes in students’ personal behavior. The index included four items, each with five ordinal response options that were logically consistent. Items were recoded and dichotomized as high or low based on the original rating scale, i.e., high corresponding with ‘to a great extent’ and low corresponding with ‘not at all.’ The Cronbach’s alpha, measuring the scale’s reliability, was .71. A mean score of 3.6 indicated a strong consensus that social work education does impact student private-life behavior.

Findings related to teaching about private-life conduct revealed that 59.3 % (n=40) of respondents believe that students should be educated about private-life conduct; the same proportion also indicated that students ought to ensure that private-life behavior aligns well with the ethical principles of the profession.

Open-ended comments were varied, with many commenting on the perceived impact of social work education on student OWB.

- “Exposure to new ideas and information can have an immediate impact on some students, though not all.”

- “Teaching may plant a seed, but whether it leads to changes in thoughts and behavior depends largely on life experiences and environment.”

- “Social work education and the university environment may not necessarily make students more sensitive, but might make them hesitant to express their true beliefs.”

- “Most students would likely have reservations about these issues before taking social work classes, but if they hadn’t considered them, the classes could have an impact.”

Limitations

Study limitations include the small sample size and limited geographic variability, as most respondents indicated residence in the Northeast. This region leans more democratic, which could have produced a potential bias in perceptions of ethics and OWB. In addition, the sample only included faculty from the United States, limiting generalizability and an international perspective. As well, the non-probability sampling method could also limit generalizability; that is, faculty whose contact information was unavailable from their institution’s website were not included in the study. This limitation is a drawback of convenience sampling. Method of contact could also have led to self-selection bias; in effect, the study may have attracted only those faculty members who have an interest in ethics or private-life behavior. In addition, as social work faculty, respondents are a group who have an interest in promoting a positive perspective of the profession, which could have resulted in some bias.

Discussion

Professional associations direct their membership to uphold certain ethical standards in both personal and professional life. Society expects professionals to exhibit and embody these standards as well. The respondents of this study suggest that this perspective extends to social work, with nearly two-thirds (62.5 %, n=40) asserting that social workers should be held to a higher moral standard compared to other professionals. Additionally, a substantial majority of respondents (73.4 %, n=47) believe that society expects social workers to maintain high moral character both in their professional and personal lives. Further support comes from 68.7 % (n=44) of respondents who feel that social workers should serve as moral exemplars for society.

Opinions diverge, however, when it comes to the oversight of personal behavior. While 39.1 % (n=25) of respondents support some level of employer oversight regarding off-duty conduct, a significant proportion oppose such intervention. This resistance also extends to state licensing regulation, with nearly three-quarters (70.3 %, n=45) of respondents suggesting against board oversight of OWB.

This study sought to explore how social work faculty view OWB as it relates to both the profession and education of social workers. Some professions, in their ethical standards, provide specific guidelines regarding the expectations and behavior of practitioners in their private lives. We see this in law Braverman & Snyder, 2022; Corker, 2020), psychology (NASP, 2020), and other professions. At one time, the social work NASW Code of Ethics included the principle of propriety (NASW, 1979), articulating an expectation that social workers maintain high standards of personal conduct. Charles Levy, whom some have noted as the grandfather of social work ethics (NASW Massachusetts Chapter, 1999), suggests that:

“What is generally expected of the practitioner is that he should have high standards of personal or ‘moral’ conduct. The objective for the practitioner is to avoid any conduct in his [or her/their] private life that might be carried over to his [or her/their] occupational life. The principle of propriety cautions the practitioner to avoid doing anything that would generate public doubt about his [or her/their] honesty or morality as a practitioner or about the trustworthiness or his [or her/their] colleagues as a group” (Levy, 1974, p. 209).

The IFSW Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles (2018), the NASW Code of Ethics (2021) and other social work codes worldwide imply through emphasis on social justice, social change, empowerment of the vulnerable and oppressed, advancing racial justice, and through the principles of service and integrity, that social workers are expected to uphold certain values in both professional and personal lives. These values are indicative of living a moral life in ways that envisage social workers as stewards of ethical integrity. The respondents of this study overwhelmingly support the idea that social workers conduct themselves according to a high standard of moral integrity.

When it comes to teaching students about private-life behaviors, faculty consider it important to speak with students about private-life moral conduct. Research suggest that schools play an important role in influencing the values of students (Brandenberger & Bowman, 2015; Corker, 2020; Seijts et al., 2022). Commentators do suggest that educational institutions ought to emphasize character development (Corker, 2020; Brandenberger & Bowman, 2015), and our findings reinforce the notion that integrating discussions on OWB into curricula is both relevant and necessary.

At the undergraduate level, universities are encouraged to focus on character formation alongside academic learning (Seijts et al., 2022). It seems reasonable to suggest that this becomes even more important in post-graduate terminal degree programs like social work. In agreement, a majority of respondents (59.3 %, n=38) advocate for incorporating discussions on private-life behavior into the curriculum.

Implications

These findings suggest several implications, with specific attention to integrating personal conduct standards into the education and practice of social workers. These implications can be instructive regarding how private-life activity relates to the profession and to the education of social work students.

Moral Standards and Integrity

A majority of respondents assert that social workers ought to be held to high moral standards and act as moral exemplars. Both the historical and current culture of the profession, which emphasizes values of social justice, integrity, and empowerment, support this perception. OWB, which includes such things as prejudicial comments, telling offensive jokes, or displaying social media images of drunken behavior, could contribute to a sullied societal perception of the profession. Further standards developed by organizations like IFSW have the potential to reinforce already established guidelines that emphasize the importance of integrity and propriety in private-life behavior.

Oversight of Private-life Behavior

Opinions regarding external monitoring were generally mixed, though support for external oversight of OWB was in the lower range. Those who do support oversight could be particularly focused on the profession’s standing in the public eye. For instance, one respondent stated, “I am not really in favor of big brother watching, but I am concerned that a few bad apples could really damage our reputation.” The majority of respondents, however, indicated strong opposition to private-life oversight. These diverse opinions suggest a need to support private-life privacy but not at the expense of compromising the profession’s standards of conduct. Perhaps this could involve the creation of more explicit guidelines around integrity and propriety, similar to NASW’s 1979 Code, but without external monitoring or scrutiny. This would maintain respect for privacy and autonomy while suggesting self-monitoring that keeps in mind private-life responsibilities.

The Role of Educational Institutions

Given that 59.3 % of faculty advocate for integrating private-life conduct discussions into social work education, schools should consider incorporating content that addresses both professional and private-life behavior into the curriculum. Content on OWB could be instructive in helping students navigate private-life activities, such as digital communication, in which boundaries have become increasingly blurred.

To summarize, findings suggest that any integration of OWB into social work education requires thought and sensitivity that takes into account the diversity of opinion that appears to exist on the matter. Though some OWB content areas may only be moderately embraced as central to social work education, the values underlying ethical and moral considerations of OWB directly support both professional standards and societal expectations.

Conclusion

Faculty perceptions indicate that social workers ought to serve as moral exemplars, adhering to high moral standards in their private lives. This expectation coincides with the general public, as there is certainly evidence that deviations could adversely affect the profession’s reputation and weaken public trust. Support for adhering to moral private-life behavior is also found in the IFSW (2018) Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles. These expectations, coupled with social work’s esteemed reputation as one of the most value-based professions (Chechak, 2015; Osmo & Landau, 2003; Reamer, 2018), engenders considerable responsibility.

Some commentators argue that private-life behavior is just that, private, and should not be subject to scrutiny (Lippke, 1989; Olivier, 2006). This opinion does tend to contrast with the perspectives of professional social work organizations and agencies, the general public, and the respondents of this study, all of which suggest that for professionals, private-life rights are not absolute. In the past, perhaps OWB had less visibility, existing only peripherally with minor seriousness. However, given the proliferation of social media and other virtual environments, where personal lives are displayed with excruciating detail in front of the world, private-life behavior does become a public matter. Students need guidance in juxtaposing private-life conduct with professional standards. Creating a space for these conversations seems well-advised.

References

Abel, J. (2022). Cop Like: The first amendment, criminal procedure, and the regulation of policy social media speech. Stanford Law Review, 74(6), 1199-1282.

Adusumalli, M., & Jainer, N. (2020). Integrity as a value of social work. In A. Kurian, M. Adusumalli, N. Jainer, J. Sheeba (Eds.), Block-3: Values of social work-I (pp. 45-53). Indira Gandhi National Open University. Retrieved from

https://egyankosh.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/67072/3/Unit-3.pdf

Allen, A. (2003). Privacy isn’t everything: Accountability as a personal and social good. Alabama Law Review, 54(4), 1375-1391.

Althoff, B. (2000). Big brother is watching: Discipline for private conduct. In ABA Center for Professional Responsibility (Ed.), The professional lawyer: Symposium issue (pp. 81–106). American Bar Association.

Banks, S. (2016). Professional integrity: From conformity to commitment. In R. Hugman & J. Carter (Eds.), Rethinking values and ethics in social work (pp. 49–63). Palgrave Macmillan.

Barsky, A. (2019). Ethics and values in social work: An integrated approach for a comprehensive curriculum (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Barsky, A., Carnahan, B., & Spadola, C. (2021). Licensing complaints: Experiences of social workers in investigation processes. The Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 18(2), 29–42.

Bisman, C. (2004). Social work values: The moral core of the profession. The British Journal of Social Work, 34(1), 109–123.

Boland-Prom, K., Johnson J., & Gunaganti, G. (2015). Sanctioning patterns of social work licensing boards, 2000–2009. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(2), 126-136.

Brandenberger, J., & Bowman, N. (2015). Prosocial growth in college: Results of a national study. Journal of Moral Education, 44(3), 328-345.

British Association of Social Workers. (2002). Code of ethics. British Association of Social Workers.

Bryan-Brown, C., & Dracup, K. (2003). Professionalism. American Journal of Critical Care, 12(5), 394–396.

Butler-Warke, A., & Bolger, J. (2021). Fifty years of social work education: Analysis of motivations and outcomes. Journal of Social Work, 21(5), 1019-1040.

Byrne, N. (2019). Social work students’ professional and personal exposure to social work: an Australian experience. European Journal of Social Work, 22(4), 702–711.

Chechak, D. (2015). Social work as a value-based profession: Value conflicts and implications for practitioners’ self-concepts. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 12(2), 41-48.

Clark, C. (2006). Moral character in social work. British Journal of Social Work, 36, 75–89.

Congress, E. (2001). Dual relationships in social work education: Report on a national survey. Journal of Social Work Education, 37(2), 255-266.

Cook, W., & Kuhn, K. (2020). Off-duty deviance in the eye of the beholder: Implications of moral foundations theory in the age of social media. Journal of Business Ethics, 172(3), 605-620.

Corker, J. (2020). The importance of inculcating the ‘pro bono ethos’ in law students, and the opportunities to do it better. Legal Education Review, 30(1), 1–15.

Cornwell, J., & Higgins, E. (2019). Beyond value in moral phenomenology: The role of epistemic and control experiences. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 2430.

Currer, C. (2009). Assessing student social workers’ professional suitability: Comparing university procedures in England. British Journal of Social Work, 39(8), 1481-1498.

DiCenso, D. (2005). Conduct unbecoming a teacher: A study of the ethics of teaching in America. (Publication No. 3197667) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Drouin, M., O’Connor, K., Schmidt, G., & Miller, D. (2015). Facebook fired: Legal perspectives and young adults’ opinions on the use of social media in hiring and firing decisions. Computers in Human Behavior, 46(1), 123-128.

Drude, K., & Messer-Engel, K. (2020). The Development of Social Media Guidelines for Psychologists and for Regulatory Use. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 6(12), 388-396.

Duncan-Daston, R., Hunter-Sloan, M., & Fullmer, E. (2013). Considering the ethical implications of social media in social work education. Ethics and Information Technology, 15(1), 35–43.

Fang, L., Mishna, F., Zhang, V., Van Wert, M., & Bogo, M. (2014). Social media and social work education: Understanding and dealing with the new digital world. Social Work in Health Care, 53(9), 800–814.

Furness, S. (2015). Conduct matters: The regulation of social work in England. British Journal of Social Work, 45(3), 861–79.

Garner, J., & O’Sullivan, J. (2020). Facebook and the professional behaviors of undergraduate students. Journal of Higher Education Studies, 12(3), 45–60.

General Social Care Council. (2002). Code of practice for social care workers. GSCC. Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/14

Glasser, P. (1984). What happens when our values conflict with those of our clients? Practice Digest, 6(4), 4-10.

General Osteopathic Council. (2019). Osteopathic practice standards. General Osteopathic Council. Available at: https://standards.osteopathy.org.uk/

Griffin, M., & Lake, R. (2012). Social networking postings: Views from school principals. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 20(11), 1-23.

Halabuza, D. (2014). Guidelines for social workers’ use of social networking websites. Journalof Social Work Values and Ethics, 11(2), 45–56.

Hargrove, C. (2023). The private life of the pastor-theologian: How John F. MacArthur encourages godliness in the lives of pastor-theologians. The Masters Seminary Journal, 34(1), 195-217.

Holmström, C. (2014). Suitability for professional practice: Assessing and developing moral character in social work education. Social Work Education, 33(4), 451-468.

Hussain, S., Hussain, S., Khalil, M., Salam, S., & Hussain, K. (2021). Pharmacy and medical students’ attitudes and perspectives on social media usage and e-professionalism in United Arab Emirates. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 13(2), 102–108.

International Association of Chiefs of Police. (2008). Police chiefs desk reference: A guide for newly appointed police leaders. International Association of Chiefs of Police.

International Federation of Social Workers. (2018). Global social work statement of ethical principles, available online at: https://www.ifsw.org/global-social-work-statement-of-ethical-principles/

Kamarudin, Y., Mohd Nor, N., Libamin, A., Suriani, A., Marhazlinda, J., Bramantoro, T., Ramadhani, A., & Neville, P. (2022). Social media use, professional behaviors online, and perceptions toward e-professionalism among dental students. Journal of Dental Education, 86(8), 958-967.

Kaptein, M. (2019). Prescribing outside-work behavior: Moral approaches, principles, and guidelines. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 31, 165–185.

Knapp, S., & Vandecreek, L. (2006). Practical ethics for psychologists: A positive approach. American Psychological Association.

Lamboo, T. (2010). Police misconduct: Accountability of internal investigations. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 23(7), 613–631.

Levy, C. (1974). On the development of a code of ethics. Social Work, 19(2), 159-169.

Lippke, R. L. (1989). Work, privacy, and autonomy. Public Affairs Quarterly, 3(2), 41-55.

Lister, M. (2022). That’s none of your business! On the limits of employer control of employee behavior outside of working hours. Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence, 35(2), 405-426.

Liu, T., Yi, S., & Zhu, Y. (2022). Does Chinese social work students’ career intention match their professional identity? The role of background factors. The British Journal of Social Work, 53(4), 2392–2415.

Marshal, M., Niranjan, V., Spain, E., MacDonagh, J., O’Doherty, J., O’Connor, R., O’Regan, A. (2021). Doctors can’t be doctors all of the time: A qualitative study of how general practitioners and medical students negotiate public-professional and private-personal realms using social media. BMJ Open, 11(10), 1-8.

Mauldin, M. (2024). The ethics of public employees’ disparaging private social media use, erosion of trust, and the advancement of the public interest. In A. Olejarski & S. Neal (Eds.), Empowering public administrators: Ethics and public service values (pp. 226-239). Routledge.

Maxwell, B. (2018). When teachers’ off-duty creative pursuits conflict with role model expectations: A critical analysis of Shewan. Interchange, 49(2), 161-178.

McBeath, G., & Webb, S. (2002). Virtue ethics and social work: Being lucky, realistic, and not doing one’s duty. British Journal of Social Work, 32(8), 1015-1036.

McLaughlin, K. (2007). Regulation and Risk in Social Work: The General Social Care Council and the Social Care Register in Context. The British Journal of Social Work, 37(7), 1263–1277.

Meadows, W. (1993). Attorney conduct in the operation of a motor vehicle as grounds for professional discipline. The Journal of Legal Profession, 18, 417-424.

Menkel-Meadow, C. (2001). Private lives and professional responsibilities: The relationship of personal morality to lawyering and professional ethics. Pace Law Review, 21(2), 365–393.

Miller, A. (2022, February 17). A simplified social worker’s code of ethics. Chron. https://work.chron.com/simplified-social-workers-code-ethics-21897.html

Milton, C. (2014). Ethics and social media. Nursing Science. Quarterly, 27(4), 283-285.

Morgenroth, T., Ryan, M., & Peters, K. (2015). The motivational theory of role modeling: How role models influence role aspirants’ goals. General Psychology, 19(4), 465-483.

Mukherjee, D., & Clark, J. (2012). Students’ participation in social networking sites: Implications for social work education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 32(2), 161-173.

Musschenga, A. (2002). Integrity: Personal, moral, and professional. In A. Musschenga, W. van Haaften, B. Spiecker, & M. Slors (Eds.). Personal and moral identity (pp. 169-201). Springer.

Nasri, N., Mohd Rahimi, N., Hashim, H. (2023). Conceptualization of e-professionalism among physics student teachers. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 12(3), 1346.

National Association of School Psychologists. (2020). The professional standards of the National Association of School Psychologists. https://www.nasponline.org/standards-and-certification/nasp-standards

National Association of Social Workers. (1979). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Author.

National Association of Social Workers. (2021). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Author.

National Association of Social Workers, Massachusetts Chapter. (1999, July). Ethical issues across the fields of practice. FOCUS Newsletter. Retrieved from https://www.naswma.org/page/107/Ethical-Issues-Across-the-Fields-of-Practice.htm

Noble, D., & King, J. (1981). Values: Passing on the torch without burning the runner. Social Casework, 62(10), 579–584.

Norris, P. (2021). Cancel culture: Myth or reality? Political Studies, 71(1), 145-174.

Oakley, J., & Cocking, D. (2001). Virtue ethics and professional roles. Cambridge University Press.

Olivier, S. (2006). Moral dilemmas of participation in dangerous leisure activities. Leisure Studies, 25, 95–109.

Osmo, R., & Landau, R. (2003). Religious and secular belief systems in social work: A survey of Israeli social work professionals. Families in Society, 84(3), 359-366.

Reamer, F. (1995). Malpractice claims against social workers: First facts. Social Work, 40(5), 595-601.

Reamer, F. (2003). Boundary issues in social work: Managing dual relationships. Social Work, 48(1), 121-133.

Reamer, F. (2013). Social work in a digital age: Ethical and risk management challenges. Social Work, 58(2), 163–172.

Reamer, F. (2017). Evolving ethical standards in the digital age. Australian Social Work, 70(2), 148-159.

Reamer, F. (2018). Social work values and ethics (5th ed.). New York: Columbia University Press.

Reamer, F. (2023). Boundary issues in social work: Managing dual relationships. Social Work, 48(1), 121-133.

Rhode, D., & Woolley, A. (2011). Comparative perspectives on lawyer regulation: An agenda for reform in the United States and Canada. Fordham Law Review, 80(6), 2761-2790.

Ross, S., Lai, K., Walton, J., Kirwan, P., & White, J. (2013). I have the right to a private life. Medical students’ views about professionalism in a digital world. Medical Teacher, 35(10), 826-831.

Sarmurzin, Y., Baktybayev, Z., Kenzhebayeva, K., Amanova, A., & Tulepbergenova, A. (2025). Teachers are not Imams: The impact of social media on the status of teachers in Kazakhstan. International Journal of Educational Development, 113(1), 103220.

Sawicki, N. (2009). A theory of discipline for professional misconduct. Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository, Paper 267, 1-36.

Scottish Social Services Council. (2003). Code of ethics. Scottish Social Services Council. Retrieved September 5, 2024, from https://www.sssc.uk.com/knowledgebase/code-of-ethics.

Seijts, G., Monzani, L., Woodley, H., & Mohan, G. (2022). The effects of character on the perceived stressfulness of life events and subjective well-being of undergraduate business students. Journal of Management Education, 46(1), 106–139.

Staud, S., & Kearney, R. (2019). Social media use behaviors and state dental licensing boards. American Dental Hygienists’ Association, 93(3), 37-43.

Stoeffler, S., Kauffman, S., & Rigaud, J. (2021). Casual attributions of poverty among social work faculty: A regression analysis. Social Work Education, 42(8), 1109-1214.

Strom-Gottfried, K. (2003). Understanding adjudication: Origins, targets, and outcomes of ethics complaints. Social Work, 48(1), 85-94.

Strom-Gottfried, K. (2014). Ethical vulnerability in social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 36(2), 241-252.

Sweifach, J. (2011). Conscientious objection in social work: Rights vs. responsibilities. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 8(2), 1-14.

Tam, D., & Coleman, H. (2009). Construction and validation of a professional suitability scale for social work practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 45(1), 47–63.

Thompson, L., Dawson, K., Ferdig, R., Black, E., Boyer, J., Coutts, J., & Black N. (2008). The intersection of online social networking with medical professionalism. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(7), 954-947.

Whittle, S., & Cooper, G. (2009). Privacy, probity, and public interest. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford.

Wiles F. (2013). Not easily put into a box: Constructing professional identity. Social Work Education, 32(7), 854–866.

Yin, B., & Li, Y. (2023) Benefactor-versus recipient-focused charitable appeals: How to leverage in-group bias to promote donations for out-group recipients. Journal of Advertising, 52(5), 739-755.

Zinskie, C., & Griffin, M. (2023). Initial teacher preparation faculty views and practice regarding e-professionalism in teacher education. CITE Journal, 23(2), 434-455.

Appendix 1: Sample of survey questions in each section of the survey